Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (7 page)

Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

And yet, believe it or not, not all menstrual superstitions were unremittingly horrific. In many cultures, a young girl entering puberty was seen as cause for celebration. Pliny the Elder reported that Greeks and Romans believed a menstruating woman could calm a tempest and rescue ships foundering in severe storms. That, friends, ain’t hay. And remember how Pliny thought that a bleeding woman could kill insects? Well, in his words, “If a woman strips herself while she is menstruating and walks round a field of wheat, the caterpillars, worms, beetles, and other vermin will fall from the ears of corn.”Talk about a green alternative to pesticides … or should we say red?

Hippocrates himself believed menstruation would “purge women of bad humors,” bringing relief from headaches, nervous tension, and what sounds suspiciously to us like PMS. He also believed menstruation was the body’s way of getting rid of excess blood that was responsible for imbalance and disease. As a result, he concluded that men would benefit if they were purged of diseased blood, too. The Greek physician Galen took Hippocrates’ theory one step further and introduced regular bloodletting as both medical treatment and a way of balancing the blood, one of the four humors (along with yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm). He came up with an elaborate system of how much blood should be drawn based on an analysis of not only the patient’s age, health, and symptoms, but also the season, weather, and location.

As lame as it sounds, “humorism” was actually the medical rage in Western culture until the 1600s; and even after it fell by the wayside, bloodletting remained popular for both sexes throughout much of the nineteenth century, including women who were menstruating or pregnant. After the medical community rallied to denounce the practice, Edward Tilt, a renowned London physician, defiantly published a book in 1857 in which he defended the use of bloodletting to treat menopause. He argued that since it mimicked menstruation (well, kind of), it would obviously cure hot flashes, headaches, and dizziness.

And do you know who the primary bloodletters were? Not physicians … but barbers. That iconic red-and-white striped barber pole symbolized both red blood and a white tourniquet; the pole itself called to mind the stick patients were asked to squeeze in order to dilate their veins. And did you know Mr. I-Cannot-Tell-a-Lie, George Washington, first American president and father of our country, most likely died due to some overzealous bloodletting? After falling ill, he was bled repeatedly the following day for a total of eighty-two ounces, the amount in almost seven cans of Coke. Not surprisingly, he died that night.

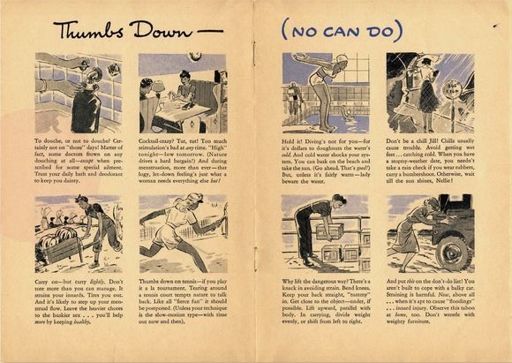

We can all breathe a collective sigh of relief that the more drastic theories and treatments of the ancient world disappeared like the morning dew in the past century as scientific discovery rendered them obsolete. And yet many superstitions about menstruation stubbornly lingered on. In a 1943 booklet put out by Kotex, “That Day Is Here Again,” common superstitions of the day were listed in a section called “When Grandma Was a Girl”:

If she drank milk, the cows were doomed.

If she entered a wine cellar, wine went sour.

Flowers would wither away at her touch … .

Meat would spoil if she dared to salt it.

A look from her eyes would kill a swarm of bees.

Clocks stopped during her period.

Did Grandma realize that many of her cherished superstitions dated back to Pliny the Elder, circa A.D. 77? The booklet quickly went on to debunk these myths, along with others involving bathing, shampooing, and exercising … but the fact that there were so many myths that actually needed debunking in the first place gives one serious pause. And despite their seeming step forward toward enlightenment, Kotex was quick to point out other limitations. They sternly warned menstruating women against imbibing cocktails—too much stimulation was bad for the system! They put a similar kibosh on swimming: sudden immersion in cold water could shock your system and stop your flow! In fact, any sort of physical overexertion was best avoided. And wet feet spelled potential disaster.

In his 1866 book, Women and Her Diseases, Dr. Edward Dixon also zeroed in on the wet foot problem. As he saw it, cold congested the uterus; sporting flimsy calfskin slippers on a chilly day would certainly be enough to stop menstrual flow. He disapprovingly mentioned patients of his, madcap girls who routinely soaked their feet in ice water in order to stave off their periods before a big party. The way to rev the flow back up again? A hot tub and a cup of herbal tea was usually enough to do the trick.

But once Dr. Dixon got on a roll, he apparently couldn’t stop theorizing, and those cold feet were just the tip of the iceberg. He wrote that girls from warm climates hit menarche earlier than those who grew up in chillier regions, who apparently only had their periods during the summer. He also expounded on the “artificial maturity” brought on by saucy novels, or too much time spent on art, music, or dancing. Any of these inherently unwholesome activities, he warned darkly, would most definitely cause puberty to start early.

Dr. Dixon wasn’t alone in his nutball theories. In his 1898 book, Confidential Talks with Young Women, Dr. Lyman Sperry was right there wagging his finger reprovingly about those cold, wet feet of ours. He also put forth the idea that since the womb and nervous system were intricately connected, anger, grief, fear, anxiety, or depression could check one’s flow. As a result, emotional girls should think twice before attending parties, picnics, or sleigh rides, all of which could stimulate a girl right into her own self-propelled menstrual suppression, wreaking havoc on her precious fertility. No smart-thinking girl should ever knowingly travel during the first few days of her period, as the stress and fatigue would throw off her schedule. But even if that dire event occurred, all she needed was a warm bed and a cup of hot tea, and everything would soon be as right as rain.

It wasn’t just menstruation that Dr. Sperry had a bee in his bonnet about. A paid lecturer on “sanitary science”—the popular movement that extolled the importance of hygiene and railed against the terrifying, unseen world of germs—he had a virtual cow about masturbation, considered one of the great social evils of the time, as well as any indulgence in “lustful and lascivious thought.” Sperry felt, perhaps a bit too feverishly, that girls hitting puberty needed to control their sexual urges, lest they permanently damage their reproductive organs. In fact, girls who “abused” those organs “seriously diminish not only their own capacity for happiness, but their power for producing healthy, happy children.”

Professor T. W. Shannon, in his 1913 book Self Knowledge and Guide to Sex Instruction, was another nattering nabob of negativity when it came to the whole idea of female self-love. Girls who masturbated and poked around where they shouldn’t be poking were clearly writing themselves a one-way ticket to lifelong pain, suffering, and worse. “The mind becomes sluggish and stupid,” he thundered. “Memory fails and sometimes the poor victim becomes insane. This habit leads to a gloomy, despondent, discouraged state of mind. Because of this mental state, many commit suicide.” At the same time, he urged mothers to teach their daughters that their reproductive organs were nothing to be ashamed of; instead, he wrote, they “form the sacred sanctuary which will one day enable her to become the sweetest and holiest of God’s creatures—a pure, happy mother.”

Is it hilariously campy or truly creepy to realize just how many outrageous, sometimes silly, often dangerous theories and myths have been dreamt up about menstruation—and how those far-fetched ideas still resonate in modern society?

Take a look at ads for menstrual suppression, menopause treatments, or medications for extreme PMS—they focus relentlessly on how much better a woman’s life would be if only she could control her blood. So let’s be frank: how far have we really come, when society is still pounding the message that our reproductive systems are faulty and need to be tinkered with, and that our bodies would work much, much better with a little help from the outside?

How did we get here? It’s where we’re headed that freaks us out.

HYSTERIA

O

A GENTEEL, TREE-LINED STREET NEAR OUR spective homes in New York City’s Greenwich Village is a charming little shop exclusively dedicated to sex toys. Inside, cheerful, fresh-faced young men and women are happy to help customers ponder the options: a dominatrix catsuit made out of PVC, perhaps, or a titanium cock ring, multicolored condoms, pineapple-flavored lubricants, butt plugs. What catches our eye, however, is the extraordinary range of vibrators available: in various colors and sizes, rotating, waterproof, egg-shaped, filled with jelly. And we wonder: do any of the friendly, nipple-ringed staff realize that the vibrator’s history is actually inextricably linked to the ancient story of hysteria and the uterus?

Hysteria, that mysterious catchall of female ailments that existed in recorded history for thousands of years, is a diagnosis that dates back to ancient Egypt. It’s associated with out-of-control emotions, irrational fears, and unregulated, over-the-top behavior, but overwhelmingly, only in women. And believe it or not, one of the most popular treatments for hysteria that literally spanned centuries was manual stimulation to orgasm by a medical doctor.

Okay, it wasn’t actually called an orgasm back then, it was a “hysterical paroxysm.” And believe it or not, it wasn’t even considered sexual; in a world ruled by a heterosexual, male-oriented notion of sex (i.e., vaginal intercourse in the missionary position), stimulating someone’s clitoris was considered therapeutic and about as racy as bandaging a head wound. That being said, we find the whole thing more than a tad kinky. Just read the instructions Pieter van Forest wrote in 1653, which makes it all pretty clear to us: “A midwife should massage the genitalia with one finger inside, using oil of lilies, musk root, crocus or [something] similar. And in this way the afflicted woman can be aroused to a paroxysm.”

Van Forest was far from the first to describe this method, and in such lingering detail, as an effective treatment for hysteria. Centuries earlier, Hippocrates, that father of modern medicine, mentioned a similar treatment in his writings. And Galen himself, that old second-century perv, wrote: “Following the warmth of the remedies and arising from the touch of the genital organs required by the treatment, there followed twitchings accompanied at the same time by pain and pleasure, after which she emitted turbid and abundant sperm. From that time on, she was free of all the evil she felt.”

And yet, the medical profession emphatically did not suggest a woman try this at home by herself (perhaps with a nice glass of wine, listening to some music, and surrounded by cushions). No, it was a medical treatment to be provided by a professional—a doctor or midwife—at a scheduled appointment, for cold, hard cash. If one were lucky, one could even find someone to stop by for a house call.

Going to the doctor’s for such a treatment was nothing like putting on an oversize gown that ties in front and scooting your bare butt down to the end of the table where the stirrups are. Back then, a woman remained not only standing, but fully clothed; the doctor would have to bend down and reach up under all of her heavy draperies in order to locate the right spot, working completely by feel. Not surprisingly, the treatment was incredibly taxing; it probably took the hapless doctor time to even find the clitoris, and after that up to a full hour to achieve the desired result. Plus it was difficult; one doctor back in 1660 ruefully compared the technique to rubbing one’s stomach with one hand while patting one’s head with the other. As a result, midwives were often employed to do the actual handiwork.

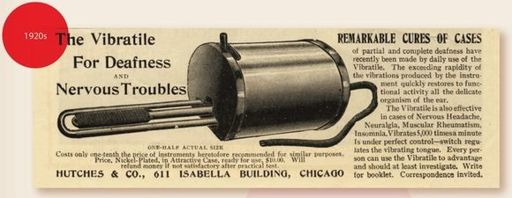

But by the late nineteenth century, the second stage of the Industrial Revolution, which had already transformed farming, manufacturing, transportation, and the face of labor forever, also brought us the vibrator. Dr. J. M. Granville, a British physician, developed a mechanical model in 1883, and overnight, doctors found they could treat hysteria patients in mere minutes instead of hours.