Folk Legends of Japan (34 page)

Read Folk Legends of Japan Online

Authors: Richard Dorson (Editor)

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Asian, #Japanese

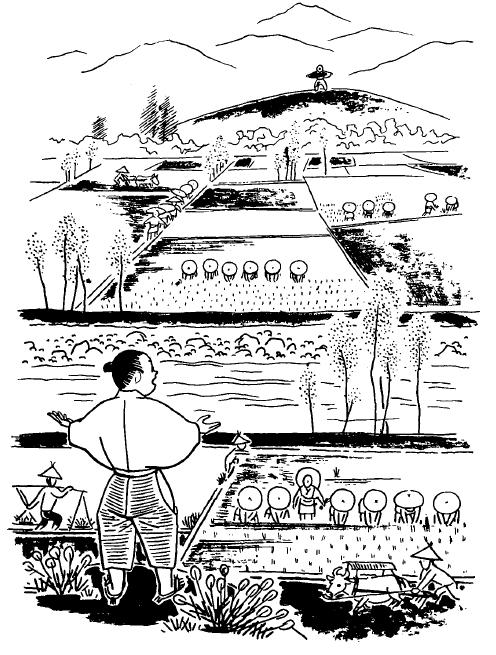

Meanwhile someone or other in Tsukada-mura said: "It would be interesting if some person from our village could compete in singing songs with Jinsaku, who seems to be quite proud of his voice." All the villagers wished that some good singer might appear to surpass Jinsaku in singing songs. Then it happened one night that a sweet voice was heard from the top of a hill in Tsukada-mura. It was fully as sweet as Jinsaku's voice. The singer was none other than a young man by the name of Hikoroku from Tsukada-mura. When Jinsaku heard Hikoroku's song, he realized that he was faced with a strong rival, and he sang and sang at the top of his voice. Thereafter the villagers often heard those two young men on both sides of the Masuda River sing in high voices, competing with each other.

The year was renewed and spring visited the lonely mountain villages of Tsukada-mura and Shogano-mura. In both villages people talked about the songs that were to be sung by the two men at rice-planting season. At last the time came. As had been expected, Jinsaku and Hikoroku competed all day long in singing their songs from each side of the river while the people were planting rice plants. Both sang and sang in their highest tones. They must have spent themselves in their competition; when the rice planting finished, Jinsaku took sick and Hikoroku, too, fell ill and lay in bed from the same day on. Strange to say, they both died about the same time.

The villagers felt very sorry for them. "They really exhausted themselves singing songs." The villagers built two burial mounds on the opposite sides of the river, east and west, for the two young men. Those mounds remain even now and go by the name of Utanosukezuka [Mounds of the Master Singers].

Townspeople say that on moonlit nights they hear clear voices singing rice-planting songs from under the mounds.

THE VILLAGE BOUNDARY MOUND

The boundary of a village was of considerable importance to its inhabitants, marking off the known from the outside, occult world, and natives returning from the outside were ritually purified when they crossed the boundary. The

Minzokugaku Jiten

discusses these ideas under

Murazaka

(Village Boundary), and

Dosojin

(God of the Boundary).

Text from

Aichi-ken Densetsu Shu,

p. 156.

O

N THE BOUNDARY

of Nagura-mura and Kamitsugu-mura there is a mound called Sakai-zuka, by a little stream at the foot of a mountain. In the olden times when the boundary of the two villages was not clear, the people of the two villages talked together about setting the boundary. They decided to set it at the point where persons who started from Nagura-mura and Kamitsugu-mura would meet. The man from Nagura-mura should lead a cow, and the man from Kamitsugu-mura should lead a horse.

When the appointed day came, the man from Nagura started early in the morning and hastened the cow along by whipping her, in order to make her go faster than the horse. So he went over the mountain to a place where he could see the village of Kamitsugu. On the other hand, the lazy man from Kamitsugu woke up late in the morning. He started riding the horse in a hurry. The man of Nagura, seeing this, waited for him by a stream at the foot of the mountain. So therefore it was decided to set the boundary there.

This is the reason why Nagura-mura's boundary is peculiarly shaped, and bigger than it should be.

OKA CASTLE

Under "Hakumai-jo" (Rice Castle), the

Minzokugaku Jiten

mentions forty variants of this legend. European counterparts are indicated under Motif K2365.1, "Enemy induced to give up siege by pretending to have plenty of food." Herodotus and Ovid employed the theme, and the Grimms have examples in their collection of German Sagen. Usually the ruse of substituting rice for water is not discovered, but Murai, pp. 3-6, "Another Version of the Origin of Hime-gana," has a spy report the deception, as does the traitor in the present instance.

Text from

Bungo Densetsu Shu,

pp. 91-92. From Naori-gun.

A

LONG, LONG TIME AGO

Oka-jo [Oka Casde] stood in Takeba-machi. A river encircled the castle. Had the river contained much water, no force however strong could have destroyed this castle. But in those days the river had little water. When the soldiers of Satsuma invaded the province of Bungo, the people inside Oka-jo were worried about the lack of water in this river. In consequence, they decided to make the river seem full of water by filling it with rice. To put rice in the entire river was not an easy task, but they accomplished it in four days. The following evening the soldiers of Satsuma marched against the castle with shouts. But after a while no sound was heard. It was because they had withdrawn, giving up the attack on seeing the river full of water.

The people within the castle were exceedingly pleased and relieved. The next day they held a feast. As they were besieged, they had only some sardines and a few appetizers with which to celebrate. So two sardines were given to each man. It happened that two sardines were lacking to supply one foot-soldier. When the lord of the castle heard this, he said: "Never mind about that one foot-soldier. He can do without any sardines." The soldier was mortified at these words. "It is too insulting. I am a human being just like the others. Since the lord has such a hard heart, I have an idea how to humble him."

That night the soldier was missing from the castle. All the other soldiers in the castle slept in peace. But suddenly they were alarmed by terrible shouts from the outside. Being totally unprepared for battle, they were thrown into a tumult. In the meantime the soldiers of Satsuma poured into the castle, and the castle was easily overthrown.

It is said that Oka-jo was destroyed because the lord did not love his servants and was blinded by greed.

THE LAUGHTER OF A MAIDENHAIR TREE

The motifs of "Dying man's curse" (M411.3), "Murder by hanging" (S113.1), "Punishment: choking with smoke" (Q469.5), and "Hanging as punishment for murder" (Q413.4) are present.

Text from

Tosa Fuzoku to Densetsu,

pp. 81-82.

A

BOUT A HUNDRED

and seventy years ago there was a greedy village headman named Hattori Goemon at Makinoyama in Kami-gun. He dealt harshly with the villagers. When men failed to bring him the rice tax, he hung them upside down from a big maidenhair tree in his yard and killed them with smoke from a fire of green pine leaves. So cruel was he that everyone hated him.

One year when the villagers had suffered a bad harvest, a man named Heiroku went to Goemon on their behalf to ask for remission of the tax. Goemon would not listen to their suit. He seized Heiroku, hung him from the maidenhair tree, and killed him with smoke. Heiroku died crying out in pain: "Kill me at once if you are going to kill me. My grudge will cast a spell on your family to the seventh generation."

After that, many strange things happened in Goemon's house, and Goemon himself went mad. At last he hanged himself from the same maidenhair tree. It was said that horrible laughter was heard from that tree on rainy evenings. This Hattori family died out after seven more generations.

This tree was called Heiroku Maidenhair Tree. A little shrine was built under the tree for the dead spirit.

THE DISCOVERY OF YUDAIRA HOT SPRING

This legend is a thoroughly Japanese variation on Motif B155.1, "Building site determined by halting of animals," well known throughout Europe. A holy hot spring replaces the building.

Text from

Bungo Densetsu Shu,

pp. 52-53, from Oita-gun.

A

CCORDING

to tradition, Yudaira Hot Spring was first discovered by Fujiwara Hidekatsu during the reign of the Emperor Kameyama. After he had traveled through many countries, he came to this place and named it Nakayama, as he thought it resembled a famous place called Sayo-no-nakayama. He built a temple there and devoted himself to converting the villagers. One day he saw a strange thing on his way back from a villager's home. There were two monkeys in a hollow a little distance from the road. They looked like mother and child. The mother monkey seemed to be wounded. The child monkey was chafing at the mother monkey's bosom, wondering what was the matter. Hidekatsu returned to the temple and the incident passed from his mind. Five or six days after that he saw the same monkeys again in the evening. The mother monkey seemed to be better than before. He looked at them and thought it over. Then an idea came to his mind.

The next morning he went with two villagers to the same spot where he had seen the monkeys. He had the villagers dig in the ground with their hoes. Then they found a hole from which the steam was rising. As they dug deeper, the steam rose more intensely. When the men put their hands down in the hole they cried: "Hot! Hot!" So Hidekatsu told the villagers what he had seen. They were glad to hear his word and according to his instruction they made baths in many places.

Hundreds of years passed. About one hundred and eighty years ago the priest of Myoshin-ji in Kyoto came to this place, having been inspired by a dream, and he established the present bath with the aid of the villagers.

THE SPRING OF SAKÉ

"Monkey released: grateful" (Motif B375.5) is known in India. Anesaki discusses "Grateful Animals," pp. 318-24. A spring of wine appears in the story of "Damburi-Choja," in Yanagita-Mayer,

Japanese Folk Tales,

pp. 133-34,

no. 46,

part of the treasure seen by a sleeping man's soul (Motif N531.3). Under Izumi, "Springs," the

Minzokugaku Jiten

suggests a connection between legends of springs turning to

sake

and festival rites held at springs, whose water may have been used in making holy

sake.

Text from

Bungo Densetsu Shu,

pp. 50-51. Collected by Hanako Yoshinaga.

M

ANY MONKEYS

abounded on Mt. Takasaki. Long ago a man named Nakao Kantsu lived near this mountain. As he was very poor, he prayed to the god Sanno every day for wealth. One day he set out for Tanoura to sell

sake.

As he was walking along the seashore of Takasaki, he saw a hapless monkey, crying piteously by a rock. Kantsu approached the creature and examined it. The monkey was being painfully pinched by a crab. He released the monkey from the scissorlike grip of the crab, and the monkey ran off gladly.

On his way back home that day, as Kantsu passed the same place with a load on his back, the monkey came but to meet him. It took hold of Kantsu by his clothes and guided him up the mountain. After walking about two hundred steps, they approached a spot where a beautiful spring gushed forth between the rocks. The monkey drank from the spring and seemed to be asking Kantsu to take a drink himself. So he drank the liquid from his hands. Indeed! It was a most delicious

sake.

He took this liquid to the village and sold it. In due time he made a fortune from the spring and eventually became the wealthiest man in the neighborhood.

BLOOD-RED POOL

Legends of the ineradicable blood stain that attests a crime (Motif D 1654.3, "Indelible blood") are widely dispersed; some New England instances are in my

Jonathan Draws the Long Bow,

Cambridge, 1946, pp. 171-73. Three Japanese examples are found in Murai, pp. 38-48, where primroses, grass by the side of a pond, and azalea bushes remain permanently reddened with the blood of slain victims ("Primroses on Shirouma-ga-take," "Princess' Stone on Motodori Hill" and "Azalea Girl"). The earlier story in this book, "Fish Salad Mingled with Blood," p. 105, contains a food-bloodied curse as in the present tale. The curse here is from a golden cock, a central figure in certain legends, discussed in the

Minzokugaku Jiten

under "Kinkei-densetsu."