Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (30 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

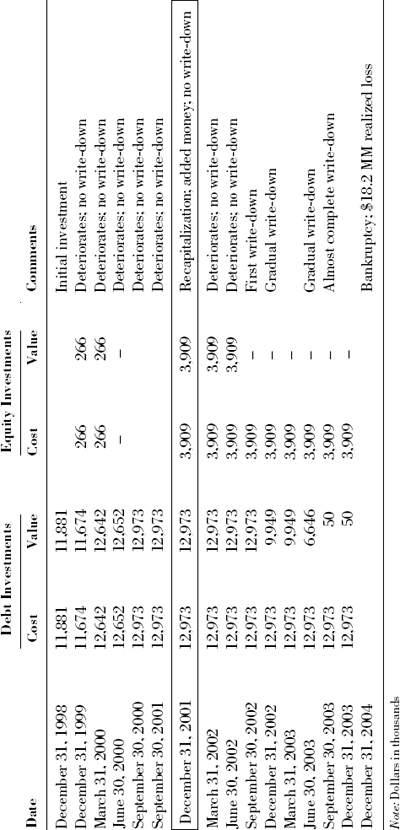

Table 22.1

Sydran Foods

On December 27, 2004, I got a phone call from our trader alerting me that Allied just announced that the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia had launched a criminal investigation of Allied and BLX. The company once again blamed short-sellers for the news. Allied issued a statement that said the investigation “appears to pertain to matters similar to those allegations made by short-sellers over the past two and one-half years.”

However, this time there was no reason to blame us. We had not contacted the U.S. attorney. The SEC is a civil regulatory agency and can commence civil investigations and actions. However, it has no criminal prosecution authority. If it finds evidence of criminal behavior, it may refer the matter to the U.S. attorney’s at the Justice Department. We didn’t know what the SEC found in its investigation, but whatever made them pass this to the U.S. attorney we considered it to be a good sign.

While Allied’s press release announcing the SEC inquiry had read, “We welcome the opportunity to . . . demonstrate once and for all that the short-sellers’ allegations are false,” Allied’s release announcing the criminal investigation did not include a similar “welcome.”

Over on the Yahoo! message board, the most aggressive poster in defending Allied’s views and attacking me personally posted as

sharonanncrayne

. This poster, claiming to be an individual investor, made 1,370 posts between May 20, 2002 (five days after my speech) and November 17, 2004. Many were quite vicious, and I suspected from their detail that they came from an Allied insider, trying to walk a fine line about providing inside information. Once the criminal investigation was announced,

sharonanncrayne

never appeared again. While we can’t know for sure, it made sense that she was an insider acting outside the lines and would stop at the sound of a criminal investigation.

Finally, two years after my speech and immediately following the criminal investigation announcement, a major media outlet actually looked at the debate between Allied and us and picked our side.

USA Today

posted on its Web site an article by Thor Valdmanis with a headline that read, “Is Allied Capital Just Another Victim of Unscrupulous Short-Sellers?” The Web site indicated that the article was intended for page 1B of the paper’s December 30, 2004, edition. The article talked about the recent investigations and Allied’s blaming us for “a vicious disinformation campaign.” The article cited a person with knowledge of the Allied case, pointing out that it isn’t unusual for the SEC to initiate a probe and then ask for Justice Department help.

“Businesses often go to their graves blaming short-sellers,” Valdmanis wrote, before concluding that “short-sellers, who often produce the best Wall Street research, can be the market’s first line of defense against corporate fraud.” After seeing the story online the night before, the next morning I bought a

USA Today

. The article wasn’t on page 1B. It wasn’t anywhere in the business section. It wasn’t in the main section. In fact, it wasn’t anywhere. I went back to the paper’s Web site—the article was gone.

In writing this book, I contacted Valdmanis, who left the paper shortly after the story was pulled, and asked him what happened. He said, “I can’t remember my editors ever explaining why the story was zapped from the Web site (and didn’t run in the print edition). But it is fair to say that kind of thing almost never happened. All I know is that Lanny (Davis) was working extremely hard at that time behind the scenes to burnish Allied Capital’s image. And we all know Lanny can be very persuasive—particularly in the face of uncomfortable facts.”

CHAPTER 23

Whistle-Blower

The federal government doesn’t like being ripped off—or at least doesn’t like the humiliation that comes with discovering it is being ripped off. The government was certainly humiliated during the Civil War, when many war contractors were overcharging it for inferior goods. So Congress passed the False Claims Act during the war, which is commonly known as the whistle-blower law. It allows people who discover fraud against the federal government to report it, and, if wrongdoing is found, to share in the money the government collects. The law also protects whistle-blowers from retribution.

Most false claim suits involve either Medicare or defense contractor fraud. The

qui tam

(the Latin abbreviation for “Who sues on behalf of the king as well as for himself”) provision of the law would allow Greenlight to file suit against Allied/BLX on behalf of the federal government and to share in any money that it recovered from BLX’s fraud. Whistle-blowers can receive from 10 percent to 35 percent of the recovery.

Between Kroll’s work and our own, we had a well-documented case of fraud at BLX. Under the False Claims Act, the case is filed under seal, which would prompt the Justice Department to investigate it and decide whether to intervene. If it intervenes, it takes over the case. If not, we would have the option to pursue the case ourselves. As we were preparing to file a case, Brickman was updating me on his latest discoveries of fraud at BLX and venting his frustration with the government, when he said, “I’m going to file a whistle-blower case.” He hired a lawyer to pursue it.

That was a problem, because there could be only one case. Under federal rules, you have to be the first case to file or your case gets dismissed. Rather than have a competition to see who would file a suit first, Greenlight’s lawyer indicated it was permissible to have multiple whistle-blowers in the same suit. I called Brickman back, admitting we were pursuing the same thing and suggested that we team up. Happily, he agreed.

- In Michigan, there were a number of loans to affiliates of Imad Daeibes (whose name is spelled differently in various documents). One of the bad loans in the loan-parking arrangement had been to Dibe’s Petro Mart. In pursuit of collecting on that bad loan, Allied took legal action and obtained a judgment in June 2002. Daeibes failed to show up for a creditor’s exam, and an arrest warrant was issued. Notwithstanding this history, BLX extended at least five additional loans in transactions that involved Daeibes. For example, on December 8, 2003, Daeibes purchased a gas station for $350,000 and resold it the same day to Tawfiq Alfakhouri for $1.2 million. BLX financed the inflated purchase. This was an obvious sham transaction called a property flip. Several of the other loans appeared to be related to similar property flips.

- There were several additional fraudulent loans involving Abdulla Al-Jufairi in additional property flips and in “piggyback” loans, where the SBA was placed in a subordinated position. Brickman also found evidence of loans where the borrower didn’t make the required equity injection. The SBA requires equity in its loans to ensure that the buyer has “skin in the game.” In one court record, Daryoush Zahraie was asked about a $240,000 down payment. He said it wasn’t made due to a verbal agreement at closing. In the same case, Zahraie testified that “Pat Harrington [BLX executive vice president in Detroit] and Al’Jafairi were sometimes business partners and had perpetrated fraudulent mortgage transactions in the past where Al’Jafairi greatly profited by the transactions and where the price of the transaction in question, including this one, was inflated because of his wrongful dealing with Plaintiff executive, Pat Harrington.”

- In New York, the EPA cited White-Sun Cleaners for major environmental violations on April 12, 2001. The next month, BLX issued an SBA guaranteed loan for $1,330,000 for the property. Initially, 34th Street Associates owned it. The U.S. Department of Labor had sued one of 34th Street’s general partners for mob connections and breach of duty as trustee of Teamsters Union 363. In August 2001, 34th Street Associates sold the property to White-Sun Cleaners, the tenant. BLX issued a replacement loan to finance the purchase. In August 2003, BLX assigned the note to the SBA because White-Sun Cleaners defaulted.

- In Illinois, BLX issued a $990,000 SBA loan to Inter Auto Inc. to bail out Witold Osinski, a borrower already in default on a $280,000 first loan to a local savings association. This violated SBA policy by transferring a credit loss from a private lender to the government. The loan was supposedly made to a body shop. Inside was an insurance scam. In 2004, Mr. Osinski was indicted for paying people to stage false auto accidents and submitting fraudulent claims to insurance companies. He reached a plea agreement with the U.S. attorney’s office, agreeing to cooperate on another case in return for a reduced sentence. He received up to 71 months in prison. Ingrid Osinski, his wife, pled guilty to one count of Frauds and Swindles and was ordered to pay $450,000 in restitution and sentenced to thirty-three months in prison.

These were just a few examples of Brickman’s discoveries. In January 2005, Kroll had a follow-up conversation with the SBA. Kroll reported that the Office of Inspector General’s (OIG’s) investigators, along with SEC investigators, were working together and had looked into many of BLX loan files and found many problems with its operating practices. The probe was focused on origination fraud, rather than accounting fraud. The OIG interviewed two former BLX loan origination employees, who provided good evidence of improper loan origination practices. The head SBA investigator met with the U.S. attorney in Washington, D.C., in early December to discuss their findings.

I thought Allied’s board should be made aware of our findings, so I wrote its directors a letter in March 2005, informing them that BLX engaged in a huge fraud against the SBA and United States taxpayers. I said that BLX maintained its loan origination volume by repeatedly flouting SBA lending regulations, including using inflated appraisals, failing to verify equity injections, permitting impermissible property splits and property flips and committing other violations. Allied used the fraud to receive income from BLX and increase its valuation of BLX. I also wrote the directors about my stolen phone records and reminded them of their obligation to investigate and ensure that those engaged in this sort of misconduct don’t serve in a management capacity in a publicly traded company or engage in this conduct at the company’s direction.

I explained to the directors how management had established a pattern of dishonesty. Walton and Sweeney were charismatic and I considered it possible that they had deceived the directors as they had Allied’s shareholders and others. Now that the company was under investigation, board members might begin questioning management. Perhaps they would now take our charges more seriously, and my letter was an attempt to open a dialogue with them.

I pointed the directors to Sweeney’s comments in the February 2003 conference call denying that she knew why, or even if, the SBA was gathering information about BLX. She had said that only days after she personally executed the agreement to unwind the loan-parking arrangement, while BLX simultaneously reimbursed the SBA $5.3 million in related guarantee payments for the parked loans. I noted the shoddy disclosure relating to the whole circumstance by saying, “This raises serious issues about the honesty of management with its shareholders and perhaps with the board. As the board of directors could not have sanctioned such public misrepresentations, the question you need to ask is, are they lying to you as well?”

A week later, Brooks Browne, the chairman of Allied’s Audit Committee, sent me a dismissive letter. The board said it asked Allied’s management and outside counsel for a response to Greenlight’s claims of misconduct. According to Browne, the information from Allied’s management did not support our accusations. Moreover, the letter didn’t mention any of the specific concerns I raised, including the theft of my phone records. Instead, it noted Greenlight’s short position against the company, implicitly attacking my credibility. The letter said if I could “provide (the board) with specific information upon which you base your allegations” then the Audit Committee could “determine whether further action is warranted.” I thought my letter was rather specific. It sure didn’t sound like they were terribly interested in getting to the bottom of the matter.

In Allied’s first SEC quarterly filing (for the first quarter of 2005), after receipt of my letter, the company dramatically reduced the summary information about BLX’s performance that it had provided since the middle of 2002. There was still enough information to track how much income Allied recognized from BLX and how fast BLX’s debt grew. However, Allied stopped disclosing origination volumes; revenue; earnings before interest, taxes, and management fees (EBITM); net income; the size of the loan portfolio; and the amount of residuals, among other things.

Brickman wrote a lengthy letter in June 2005 to Janet Tasker, the SBA associate administrator for lender oversight. Tasker was responsible for renewing BLX’s preferred lender status. The letter detailed many dubious loans and said that to protect the SBA and taxpayers from further losses, BLX’s preferred lender status should not be renewed. Despite the evidence, the SBA renewed the license for another six months. This was unusual because renewals were usually for one or two years.

Meanwhile, Brickman continued digging into BLX’s loans. He discovered a large number of dubious shrimp-boat loans. In fact, the company became the major lender of SBA guaranteed loans in the shrimp-boat industry. The data showed that BLX made no shrimp-boat loans in 1998, but made 20 percent of all such loans in 1999. That number climbed to 58 percent in 2000 and 75 percent in 2001 and 2002.

The sudden and rapid increase in the percentage of loans was particularly suspicious because cheaper shrimp from fish farms, foreign competition, higher fuel prices, and falling shrimp prices hurt the industry operating out of the Gulf of Mexico. Moreover, SBA rules required shrimp-boat loans to have a certificate from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), indicating that the NMFS declined to provide assistance to the borrower but had no objection to the SBA’s providing a loan. However, the NMFS determined that it would not provide certificates due to the overcapacity of the industry.

Brickman obtained a representative letter from the NMFS to BLX, which read, “My management also expresses the opinion that none of the fisheries in the country needs additional capacity and no Government agency should be extending financing which increases harvesting capacity. In this regard, we will be unable to provide you with documentation of our consent to the proposed financing.” While other lenders responded by abandoning the industry, BLX stepped into the void and issued loans, despite the missing certificate. Over 70 percent of BLX’s shrimp-boat loans eventually defaulted, and most of these loans came out of the Richmond office of the convicted felon McGee.

Brickman found one case where BLX made a $1.1 million boat loan in 2002 to Hung Vu. Hoa Nguyen witnessed the loan. Hung Vu defaulted in 2004, and BLX bought the boat with a “credit bid” of $1,000. Brickman’s work indicated that the real value was about $300,000. BLX then made a $750,000 loan to Hoa Minh Nguyen on the same boat. The second loan allowed BLX to delay recognizing a loss and increased the liability to the U.S. taxpayer. (In an interview, Hung Vu indicated that he was a mechanic and never made any equity injection. In fact, the boat belonged to two of his uncles who already had financial problems on other boat loans.)