Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (8 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

Rather than argue, I moved to a more dramatic example. I asked her to compare the risk in Allied’s portfolio to non-investment-grade commercial bank loans, which would have better asset protection, seniority, and even tighter covenants than the loans Allied made. Though these loans were plainly safer than Allied’s subordinated loans, industry figures indicated they recently suffered much greater losses than 1 percent per year.

Roll replied that banks aren’t structured to work out problem credits. Their regulators pressure them to dispose of non-performing assets, so they can’t be as patient. As a result, they would have to “take haircuts on getting out of an investment that we wouldn’t be willing to take because we have staying power,” Roll concluded.

It was now clear to me what was going on. The company had a qualitative method of valuation, where write-downs occurred only when they determined money would be permanently lost. They could hold the investments as long as they wanted to, for years perhaps, hoping that they would eventually get their money back and avoid a loss. As a result, they reported a loss rate superior not just to high-yield bonds, but also to much safer senior bank loans. This made no sense.

I pictured Allied management sitting in a room saying, “Do you think we’ll eventually get our money back?”

“I think so. This business could turn up.”

“All right, then we don’t need to take a write-down.”

I knew this had nothing to do with fair-value accounting.

We continued the conversation, covering specific problem investments. One of them, Cooper Natural Resources, had performed “sideways,” a euphemism for performing badly, but not yet bankrupt. The senior lenders asked Allied to convert its debt instrument into equity. Allied did that, but did not reduce the value. Roll admitted that Cooper performed below plan and the balance sheet needed to be restructured to appease the senior lender.

“Why wouldn’t that lead to some, even modest, mark-down in value?” I asked.

“Because sometimes in these cases, you haven’t really moved any further down the balance sheet,” she said. “You just recharacterize it in a different security—and if you look at the long-term projections of the company, then we were still in the money . . . so, when you look at the value of the company, you have to look at where they are today. But you also have to look in the future, and we didn’t see that we had any permanent impairment from this transaction.”

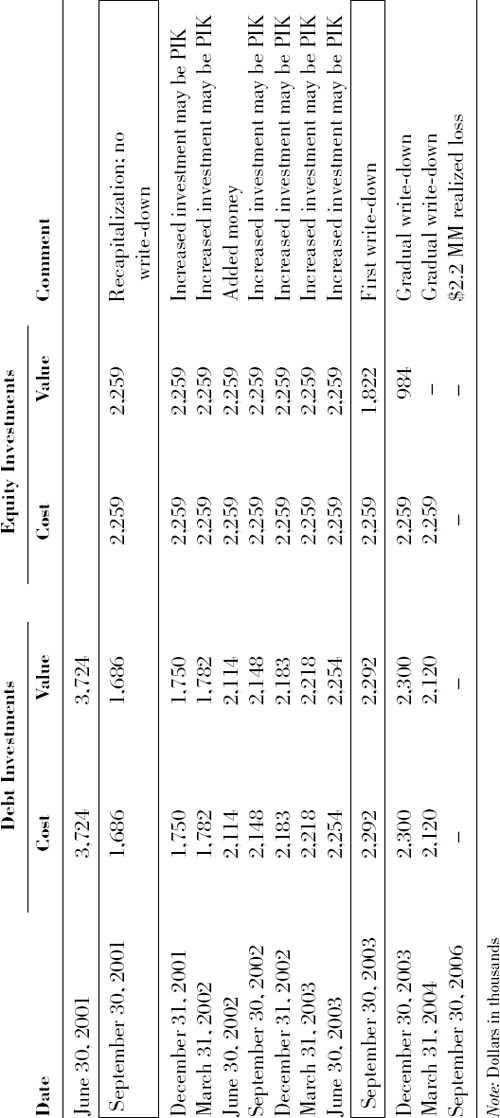

Time would reveal the suspect nature of this treatment. Eventually, in September 2003, Allied

began

to write-down the equity piece of Cooper Natural Resources. Allied valued the equity piece at zero in March 2004 and recognized a realized loss in 2006 (see

Table 5.1

).

Table 5.1

Allied’s Investment in Cooper Natural Resources

We asked about several additional investments that we suspected were troubled, including Galaxy American Communications, a rural cable provider, and three publicly traded bankrupt companies: Startec Global Communications Corporation, NETtel Communications, and the Loewen Group. We were following the Loewen Group bankruptcy because we had shorted its stock. It appeared that Allied carried its bond investment above the trading price. We asked Roll how they marked the bonds.

“What we were doing is, because there were really no trades going on in this bond once the bankruptcy hit, any trade that was made was a privately negotiated sale,” she said. “And given the status of the company, you were, if you wanted to sell versus hanging in in bankruptcy, we would just have to take probably more of a haircut than you otherwise would have. So what we were doing is, we were looking at trades, and you couldn’t really say they were market trades, as one data point. But we were on the secured [sic] creditors’ committee for a long time, so we were actually using the data we were getting from the secured [sic] creditors’ committee to value the company, on the underlying assets in the company and where they thought they would be in the emergence from bankruptcy.”

Roll’s story that the bonds did not trade was—not to put too fine a point on it—a lie. These were registered, publicly traded bonds. We received pricing sheets from dealers daily, quoting Loewen bonds at relatively narrow bid-ask spreads. There was an active market for Loewen debt, and the quotes were reliable. Greenlight itself had reviewed the possibility of buying Loewen debt several times during the bankruptcy. Her comment that a sale would cause more of a haircut was simply an admission that Allied carried the investment above market. Allied determined the value itself, based on its view that there was no objective market measuring the value. In fact, there was a market. Allied just didn’t like the price.

The conversation then turned to the limited facts disclosed about Allied’s controlled companies: BLX and Hillman. Finally, I observed that at the end of 2001, Allied’s auditor, Arthur Andersen, removed a sentence from Allied’s opinion letter that appeared in previous years. The auditors no longer opined, “We have reviewed the procedures used by the Board of Directors in arriving at its estimated value of such investments and have inspected the underlying documentation, and in the circumstances we believe the procedures are reasonable and the documentation appropriate.” Andersen had removed the same confirmation with Sirrom years before.

I questioned whether this removal indicated that the auditors conducted a lesser level of review or inspection, or perhaps didn’t agree with the values or procedures. Roll explained that the Audit Guide changed in 2001, which caused Andersen to change the standard language in its opinion. I called Greenlight’s auditor to check whether this was true. The partner on the audit researched the subject and concluded that the relevant sections were identical between 2000 and 2001. We also checked the bond prices on some of the other troubled Allied investments like Velocita and Startec and determined that Allied valued its holdings well above the quoted market prices.

Based on our independent research and what I learned on these lengthy calls with management, Greenlight put 7.5 percent of the fund into the Allied short sale at an average price of $26.25 a share.

Having been invited to speak at the Tomorrows Children’s Fund charity conference on May 15, 2002, and asked to present my most compelling investment idea, now I knew I had one. Nervously, I stepped up and made the speech. (If you have not done so already, you can see it for yourself at

www.foolingsomepeople.com

. It makes the story much easier to follow.) And yet, at that moment, I had no idea the story was really just beginning.

PART TWO

Spinning So Fast Leaves Most People Dizzy

CHAPTER 6

Allied Talks Back

After my speech, the reaction was immediate. When I showed up for work the next morning, a junior analyst from a mutual fund company that held a large long position in Allied was waiting outside our locked door. He heard that I said something important about Allied and came over to get a first-hand account. I brought him into a conference room and summarized what I had said. When I started discussing BLX, he said he hadn’t even heard of it.

When I finally got to my desk, my e-mail inbox was full of complimentary messages from people who had attended the speech, and I took a number of kind phone calls. When the stock market opened a few minutes later, there were so many sell orders for Allied that it took the specialist about thirty minutes to find a balanced price to open the stock. When it did open on May 16, 2002, the price was $21, almost a 20 percent drop. I was surprised the stock fell so far so quickly. Even so, I did not for even a minute consider covering any of our short.

I heard that Merrill Lynch told people that someone made a speech characterizing Allied Capital as another Enron. They didn’t know exactly what had been said in the speech, but they were confident that whatever was said was wrong. Obviously, one way to find out what I had said would be to contact us or ask for a copy of my speech. Though there were about a dozen analysts at brokerage firms covering Allied, not one reached out to us on that day to find out for themselves. In fact, to the date this book went to press, no brokerage firm analyst has ever done so. Whatever contact I have had with them has been at my initiation.

Allied announced it would hold a conference call later that morning to respond. When we dialed into the conference call number, we were unable to connect because the call was so well attended that Allied had not reserved enough phone lines. We called another fund that we knew was participating and listened through its connection partway through the call. Though no one from Allied contacted us to find out about my speech, nonetheless, Bill Walton, the chairman and CEO, began the call, saying, “We’ve been gathering information on this speech throughout the morning, and I think some people have actually gotten to the person who gave the speech, and so we’ve got some items here that we think we ought to discuss, but because of the fact that

we’re not really fully apprised of what we know were said last night, all of which we feel are misguided

and talk you through those and then we plan to open it up for Q&A.”

Walton began what would become a pattern of making general comments and taking personal shots, while Joan Sweeney, the chief operating officer, spun the substantive issues. Allied said it charged BLX and Hillman comparable interest rates to the rates Allied charged for mezzanine investments. Management claimed the rates were not as high as they seemed because Allied did not earn a current return on the equity investments they made to those companies. Allied encouraged investors to concentrate on the “blended” return on their combined debt and equity investment, which Allied said was not excessive. Besides, according to Allied, the controlled companies could afford to pay.

Despite management’s claim, the rates charged to the controlled companies were not customary, as no other companies paid Allied 25 percent interest. At the time, Allied charged most companies about 15 percent interest. Guiding investors to focus on a blended return that included the return on the related equity investment was a red herring, because from a legal and accounting perspective Allied treated the debt instruments as discrete from the equity instruments. In fact, Allied did earn a return on the equity investments through realized and unrealized increases in the fair-value of the investments and from dividends.

The high interest rates padded Allied’s earnings, even if BLX and Hillman could afford to pay them. Future disclosures ultimately showed that BLX didn’t have the ability to pay anyway, as it did not then, nor does it now, generate any cash. Instead, Allied periodically injected money into BLX to enable BLX to pay the 25 percent interest rate and other fees back to Allied. Sometimes, rather than have Allied infuse more money, BLX borrowed on its bank line. Since Allied guaranteed the banks against the first 50 percent of any loss on the bank line (and charged BLX a hefty fee for the guarantee), bank borrowings weren’t substantively different from Allied simply adding to its investment in BLX directly.

Next, on the issue of Andersen omitting its confirmation language from its audit opinion, Sweeney repeated Roll’s line about the Andersen audit language being removed, “The Audit Guide simply changed.”

On the issue of the funding gap created by reported earnings, which included non-cash (payment-in-kind [PIK]) income, and its required shareholder distributions, Sweeney responded, “I think what people miss in that analysis is in the case of a mezzanine loan, you’re taking cash interest for a very, very high coupon. You’re taking PIK interest for a smaller proportion, so let’s say you take 14 percent cash interest and 2 percent PIK, as long as your cash interest is above your cost of capital, the PIK is a very good thing because the PIK is added to the note and it compounds, and that note is subject to cash interest as well as PIK interest. So in a sense, PIK actually becomes accretive for shareholders, not dilutive, and really isn’t a cash drain.”

Got that? Me neither. PIK interest means that the lender accepts additional securities, growing the balance of the loan, rather than cash, as interest. It may or may not be a good thing, but Allied gave no response to my point that it has to pass the non-cash PIK income on to shareholders even though Allied has not received cash from its underlying investments to distribute.

Walton explained that cash flow, including principal repayments but before new investments, easily covered the distribution. Allied, however, did not generate cash earnings to satisfy its distribution requirements. Using principal repayments to fund the distribution without making new investments would shrink the portfolio, lowering future earnings. Essentially, this would be analogous to burning the furniture to heat one’s home.

Walton further explained that Allied’s purchases of senior debt at a discount without writing down the existing subordinated debt investment reflected fire-sales of assets that did not reflect the credit quality of what Allied bought. He added, “In fact, it was a huge opportunity for us and very good for the shareholders. Now in cases where we’re buying down senior debt of companies where we have a subordinated debt investment, we recapitalize the business and write down the subordinated debt appropriately to reflect the overall value of the business. So it’s not a question of us buying down senior debt at a discount and leaving the sub-debt in place at its previous structure and value. That simply does not happen.”

Though Walton recognized this as inexcusable, all of our research strongly suggests that this

simply did happen

at three Allied portfolio companies prior to Walton’s remark: ACME Paging, American Physician Services and Cosmetic Manufacturing Resources. Allied eventually had large write-downs on all three. The recapitalizations delayed the write-downs, giving Allied time to outgrow the problems by repeatedly issuing new shares.

Regarding fair-value accounting, Sweeney explained, “I think what people miss when they try to understand fair-value accounting is fair-value accounting takes into consideration the fact that a BDC is holding private illiquid securities held for the long term. It is not meant to take into effect the liquidation or fire-sale accounting.”

There is no such thing as “fire-sale accounting.” A fire-sale means a sale of assets at reduced prices to raise cash quickly. Sweeney invoked the colloquial term “fire-sale” because an SEC administrative law judge used the term in an opinion and indicated that investment companies should not value investments at “fire-sale” prices. I hadn’t said anything about fire-sale accounting.

For BDCs, the SEC requires fair-value accounting, the price at which an informed, arm’s-length buyer and seller would transact. For the next several weeks, Allied repeatedly and disingenuously claimed that we insisted on “fire-sale accounting.” In an effort to discredit our analysis, Sweeney redefined what I said to make it refutable. She knew most listeners hadn’t heard my speech and must have believed they wouldn’t know the difference.

Furthermore, Sweeney’s answer made no sense. The anticipated holding period is not relevant to fair-value accounting. By referring to the long holding period, she may have been referencing “hold-to-maturity” accounting, which permits loans to be held at amortized cost as long as all the holder expects are the payments to be made when due; fair-value accounting does not permit this method. Further, illiquidity is a reason to discount the value.

Walton discussed the troubled investments that had not been written down to fair-value. He started with NETtel, a bankrupt telecommunications company “that’s been written down to basically the realized value of some asset sales, which are imminent.” The truth was that at the time of this statement, NETtel had been in Chapter 7 liquidation for over a year, and its assets had already been sold. Two quarters later, Allied hid NETtel from further disclosure by quietly moving it from “investments” to “other assets” on its balance sheet. The September 30, 2002, SEC Form 10-Q showed that $8.9 million of receivables related to portfolio companies in liquidation were included in “other assets.” Though they did not disclose which investments these were, we were able to reconcile the disclosure to indicate that they included NETtel and two other investments. Five years later, Allied still has not recognized a realized loss on Nettel.

Walton described Velocita as a partnership between AT&T and Cisco Systems. “We’re in the senior debt,” he said. “We took down [the value] aggressively in the first quarter of this year to about $4 million, which is roughly where we think the company is fairly valued. We do understand that Cisco has written down its investment. But Cisco is in the equity, which, of course, is the first thing to go in a troubled telecom situation. We’re in with a fairly sophisticated group of bondholders here, and we think there are some very interesting recovery possibilities.”

Allied wasn’t in the senior debt but the subordinated debt. Cisco held the equity

and

the senior debt. Cisco wrote both to zero two quarters earlier. As for the interesting recovery possibilities, weeks later on its June 30 balance sheet, Allied recognized its Velocita bonds to be worthless.

“In the case of Startec,” Walton continued, “if you look at the statement of loans and investments, we have a $24 million debtor-in-possession (DIP) facility, which is the first money out, and this is a company with roughly $130 to $140 million of revenue and operating above . . . breakeven . . . so there’s value here and certainly there is value in our DIP instrument. We’ve also got a $10 million secured piece of paper in there, which we also feel, based on our views about how the company will come out of bankruptcy, will be money good.”

Startec’s bankruptcy records indicated monthly revenues had fallen to $5 million. Eventually, we learned that Walton’s quoted revenue figure included revenue from discontinued business lines. Startec, a communications company, was losing money and burning cash. Again, weeks later, on the June 30 balance sheet, Allied wrote the “money good” portion to zero.

Dan Loeb, who manages Third Point Partners and is never afraid of asking tough questions, asked the first question on the call. “On your fair market valuation, you seem to draw a distinction about where things trade versus where you mark them.”

“Let me be clear, they don’t trade,” Walton interjected.

“Okay, but let me give you an example,” Loeb said. “Velocita debt does trade. It trades at about two cents on the dollar. My understanding is that you are carrying Velocita at a price of forty. And these aren’t just distress fire-sale, you know, sales. This is a real market level.”

Sweeney argued, “Yeah, but I think you also have to look and say, ‘Is that a market?’ I mean, in the case of Velocita, if it trades at all, it’s by appointment.”

“Well, I can make an appointment to buy those bonds at two,” Loeb responded. “Yet, you’re still carrying yours at forty.”

“Yeah, but the question is, who are you buying them from because . . .”

“It doesn’t matter,” Loeb said. “I mean, there is a level. Put it this way, you’re so far off the market. Put it this way, are you buying more bonds, then, at these levels? Are you buying them at twenty, twenty-five, and thirty?”

“No, because that’s not our business to do that,” she said.

“Look at it this way,” Walton said a moment later. “We had a total investment in this that’s roughly $15 million. It’s down to $4 [million] and we feel that’s a very aggressive write-down. We’re evaluating the situation as we go forward. We’re working with—talking with management, etc., etc. If we feel like it’s going to be less than that based on our continuing to work with it, we’ll take it down the rest of the way.”

“I know you have a big portfolio with a lot of things in there. That one slipped through the crack,” Loeb quipped.