Footloose Scot (22 page)

Authors: Jim Glendinning

Sure enough, in another five minutes, a young Tarahumara man carrying a half sack of corn over his shoulder arrived at the side of the bus. The driver opened the door, and the Tarahumara climbed on and took a seat. Dark skinned and slight of build, he had an athlete's look. He wore a loin cloth, primitive sandals made from rubber tires, a blouse type shirt and a baseball cap. He seemed scarcely winded after his run downhill to the river and then up the mountain slope to the road. The driver, who had spotted him ten minutes earlier and had stopped to wait for him, nodded a greeting.

Two hours later, we were in Batopilas. It was now pleasantly warm, and the bus drove past mango and avocado trees which lined the street leading to the plaza. I got off, and was accosted by a courtly elderly Mexican in a white guayaba shirt. "Are you looking for a room?" he asked. I said yes. He introduced himself as Senor Monse and told me his wife had a guest house two minutes walk from the bus stop, and asked if I would like to see the rooms. This seemed like an easy introduction to Batopilas so I followed him and, not long after, was unpacking in a small room which looked on to a shady courtyard overhung by mango, papaya and orange trees. I had arrived in Batopilas, population 1,200, elevation 1,500 deep in the Copper Canyon, and I had had a close up of a young Tarahumara.

TOURS TO COPPER CANYON

For ten years, except in 2004, I ran trips to Copper Canyon. I offered two itineraries, both of which left from and returned to Alpine. The first, five days in duration, used the Copper Canyon train known as El Chepe and crossed the mountain range, dropping down to El Fuerte on the coastal plain. The first class train left Chihuahua City at 6 a.m. which meant a 5 a.m. hotel wake up call, and a quick van ride to the station. The second class train left an hour later.

With a toot of the horn the train would depart Chihuahua City and head through the western suburbs of this city of half a million. As dawn broke we would be rolling across the Chihuahua plain and I would lead the group to the dining car, sure that they were in for a surprise. There were few more satisfying moments on the trip than breakfast in the dining car as the light dawned on the Chihuahua plain and nimble waiters served plates of

huevos rancheros.

By mid morning the line would start to climb into the sierra and after five hours it reached the mountain town of Creel, a former lumber town and now hub of the Copper Canyon region. Here we would stay the night in a modernized log cabin, Sierra Lodge, twelve miles from town. I could always count on Roberto, the manager, to be at Creel station with two Suburbans to pick us up. Never once in ten years was he late.

The construction of the rail line across the mountain range took 90 years to complete. At one point the track takes a 360 degree loop, known as the lasso. At another place, the track doubles back on itself twice as it struggles to gain altitude. Today's traveler can gaze out on forested mountain ridges from a comfortable air-conditioned coach as the train crosses the Continental Divide then drops down to the warmth and bougainvillea of the coastal plain.

The second itinerary also took the train, but only as far as Creel. From there the group went by van, dropping 6,000 feet to the bottom of Batopilas Canyon. Here the group stayed in an old fashioned hacienda, formerly the property of the principal merchant when the Batopilas silver mine prospered at the end of the 19

th

century.

Both itineraries used public buses to get to Chihuahua from Ojinaga. This was the one point, on the first day of the trip, which always caused me anxiety. I could never count on quick and smooth access through Mexican Immigration. If we missed the 10 a.m. bus departure from Ojinaga, the day's schedule was spoiled. The next departure was not until three hours later, and we would miss Chihuahua City sightseeing. Fortunately, this never happened, but it almost did on one occasion where only diplomacy tact and an elderly Spanish-speaking tour member saved the day.

The incident arose when a member of the group discovered she had left her passport at home. By this date (2007), the Mexican authorities required passports from incoming tourists. I sensed the problem could be solved by the time-honored Mexican method of the bribe ("

mordida"

or "the little bite" in Spanish). But how to handle it? The wrong way would be to say to the Mexican official "We've got a problem here, what will it take to fix it?" This is an insult to his professional standing, and invites a larger sum to fix the problem than that which a little diplomacy will produce.

The right way was to use some tact and courtesy. Fortunately, there was an elderly man in the group of Hispanic background called Pepé. I explained the situation, how we had to get the tour member through without a passport - and quickly. He understood immediately. "You stand near me, and have the money ready under your hand; and tell the others to stand back from the counter." He then addressed the official formally, introducing himself and explaining the problem. He apologized for making an extraordinary request, perhaps making for extra work. The official stared back without expression, saying nothing.

Pepé started again, complimenting the Mexican efficiency at the border, and adding how the whole group was excited about visiting Mexico. The official remained silent, shaking his head. Finally, Pepé mentioned that the lady was the group leader and responsible for recruiting the rest of the group. How sad for her not to be able to travel.

At this, the official sighed, reached with one hand for the tourist card application form and with the other for the woman's driver's license which Pepé held. "Now pass me the money" Pepé said quietly, and I slid the money under my hand across to him, and he in turn to the official. A transaction had been achieved in four minutes, respect had been shown to Mexican Immigration, and the group leader was able to travel with the rest of the group.

Both trips used the

Chepe

train for the first part of the tour and both stayed at Sierra Lodge near Creel. This elongated deluxe log cabin has no electricity but in appointments capture the spirit of the sierra: log fires, kerosene lamps, tile bathrooms with cooking from a Tarahumara kitchen staff which was usually voted the best on the trip. Large tour groups could not visit there, since it was not large enough. Often we had the place to ourselves. The location in pine woods close to a waterfall, allowed for hikes during the day. Early evening, the group would return to the lodge for margaritas and music performed by a Tarahumara group.

Once I had tested each itinerary for length, contrast and content, the tours more or less sold themselves. I always followed certain guidelines in trip planning, principally to put myself in the shoes of a first time traveler and to decide if I had provided in five or six days a good overall balanced look at the region: learning against recreation; free time versus planned group time; variety of meals; adequate guide services and one or two surprises.

Necessarily, there were some boring stretches, like getting from and back to the border. In this case I used public transportation since, apart from cost savings, a trip on a Mexican bus is an event in itself. I also liked to add some local insights by providing a dinner speaker in Chihuahua City, an American called Glenn Willeford . He was a teacher and author and lived in town with his Mexican wife. He usually talked about Pancho Villa, a local hero in Chihuahua with a larger-than-life history.

In booking my tours, I always liked to have all eventualities covered: such as what happened if the train was late. Everything was double confirmed in advance, and I had local phone numbers to use for help if anything went wrong en route. Back up plans were vital but seldom necessary since the length of the trip was limited, and before long I knew all the guides, drivers and hotel keepers. When things went wrong, the most important thing to bear in mind was not to panic the group, but simply to announce why there was a delay and what the new plan was. The key to successful tour planning is in detailed planning, with a backup plan if anything goes wrong; and not to appear helpless if anything does.

In running these tours I was helped by usually having a more or less homogeneous group as tour members. I promoted the trips locally, often with a slide show and talk in an Alpine bookshop. A wave of newcomers to the Big Bend region started to arrive in the late 1990s. Many of these people knew about Copper Canyon, wanted to go there but didn't want the problems of arranging the itinerary themselves. Joining a small group (up to twelve persons) on a proven itinerary, run by someone local, was an easy decision for them. And, over a ten year period, with one or two small exceptions, I had few customer complaints.

One minor problem occurred on an early trip when we got to Sierra Lodge. There was no hot water for a shower after the day's hike. What had happened was that a couple of mischievous local Tarahumara kids had turned off the switch which activated the generator which heated the water. A couple from Midland, Texas was quite upset by this inconvenience. I explained what had happened, and apologized. The husband was a businessman and they were frequent travelers with larger tour companies, as he let me know. The others in the group who were from the Big Bend area shrugged off the temporary upset, and had another margarita. The hot water was back on in four hours but the trip had been spoiled for the Midland couple.

A second upset involving an injury might have had more serious repercussions. A single woman, a long-time employee of Phillips Petroleum in Oklahoma, decided to give herself as a retirement present a trip to Copper Canyon. She duly drove to Alpine in a new red pickup truck, also a retirement reward, and joined the group. She had had a tough life in the corporate world, and an equally hard time bringing up two sons as a single mother. She was ready for a break.

On the two mile hike to the waterfall near Sierra Lodge, which was more or less self-guided although I always went along with the group, this woman skidded on some gravel and went down heavily, breaking an ankle. Everyone rallied round, got a wood plank for her to sit on and in teams carried her back up the trail to a point where the lodge's Suburban could reach.

She was hurting, but not complaining. Initially she was apologetic about inconveniencing the rest of the group. The lodge manager, Roberto, drove her and me to a local hospital where they confirmed that the ankle was broken, and put on a splint. The patient was impressed and touched at the local doctor's (a woman) attentiveness and care albeit in a hospital with more primitive equipment than she was used to. She was amazed when they charged her nothing. (Health services are free in Mexico, and in this case they had no routine for charging tourists).

We left the patient at Sierra Lodge, still apologizing for the trouble she was causing, despite the fact that her trip was effectively spoiled. We would continue to El Fuerte, and pick her up on the way back. Which is what we did, bringing a walker I had purchased for her. By now however, her attitude had changed. Missing out on the rest of the trip, confined to the lodge and unable to walk more than a few yards, she was ready prey for a comment by someone in another tour group that the tour leader should never have let her stray off on her own.

She confronted me with this, and I pointed out that my tours were for independent-minded persons, and that on the last trip two 80-year olds had managed the hike perfectly well, and no one else had slipped on previous tours. Unfortunately she had found someone to blame, and perhaps to sue. After arranging for her to be driven back to Oklahoma in her pickup, I wondered if there would be any repercussions.

The driver who took the patient home returned to say I had perhaps better prepare for legal action so I duly consulted a local lawyer. Launching into the background of the story before describing the accident, I was surprised when the lawyer stopped me. "No need to worry," he said, "You're not at risk."

"You haven't even heard the rest of the story," I said. "I don't need to," he replied, "You are not at risk since you are a one-man operation with no assets. You're not American Express. She will not find a lawyer to take on the case, regardless of its merits,"

I did not hear from any lawyer, or from the lady herself. I hope she reconsidered her attitude that I was to blame but I understand how that was easier than blaming herself on a mistake of her own making. I never required travelers on any of my trips to sign an insurance waiver concerning accidents since I believed local Texas residents would not think or act like that.

Travelling with Texans was always a pleasure, and led me to alter my own thinking about taking tours. Long accustomed towards independent travel, for years I had ignored the positive side of group travel. Now I was earning an income from selling tours, but I also underwent a change of attitude. This was mainly because of the sort of people who signed up on my trips: trusting, good natured and full of curiosity. I experienced very few "ugly American" attitudes.

Having learned how to be a tour guide myself (in the Big Bend region) and having watched other tour guides, good and bad, over many years and in many countries, I believe that a good tour guide can make all the difference to a travel experience for the first-time visitor. A guidebook is fine, but time-consuming; a human face can personalize and dramatize a situation so it remains in one's memory.

By 2008 violence by narco cartels in Chihuahua State was increasing so much that it was starting to affect tourism. Many large US tour companies using the Chepe train were cancelling their tours. I wondered how it would affect my tours, and I would soon find out. By 2009 no one was buying my trips and I stopped advertising. Three years on, Copper Canyon seems to be safe again for travelers. Perhaps it is time to restart my trips to this wonderful region.

VOLUNTEER–TRAVELER

_______

2004

KAZAKHSTAN

VOLUNTEER

I applied to Peace Corps as a volunteer in 2003 and completed the whole process over the phone and by mail with little delay. Peace Corps wanted to judge my motivation to see how effective I might be, and also my physical fitness. I was 66 at that time and fell within Peace Corps's upper age limit of 80. My motivation was I was interested in spending a significant amount of time in a country I did not know, in seeing how I coped with the volunteer lifestyle, and in trying to leave behind something tangible for the local people.

Talking on the phone with my recruiter in Dallas, I found that Peace Corps was anxious to attract older volunteers because of their work experience. I could claim considerable business experience, and this is what they wanted in Kazakhstan. They planned to send the first ever group of business volunteers to Kazahstan in 2004. I stated my specialty was tourism, and added that I had studied Russian for one year.

Because there were also placements in other countries also available, I first read a few articles about Kazakhstan before accepting the position. I found it was in Central Asia, the ninth largest country in the world by land mass. It was mainly flat steppe terrain, but was bordered by mountains to the west and south. It had large reserves of oil and gas, which were being extracted and provided great revenues. It had been part of the Russian Empire, and later the USSR, but had become independent with the fall of the Soviet Union.

Upon independence there were hopes for democratization, but this had not happened. Little of the income from oil and gas revenues trickled down to improve the lives of the ordinary people. To some of them, things had gotten worse. At least, in the old days, there was a feeling of security. The country's leader, President Nazarbayev, who previously had been the leader of the Kazakhstan Socialist Republic within the USSR, was now a virtual dictator. Corruption was rampant at all levels and the economy, outside of the energy business, was stalled.

We were given a two day Peace Corps orientation in Washington, DC before flying to Kazakhstan. Much of this was predictable and useful to a degree. There was an inspirational talk by a senior staff member, and a couple of talks by volunteers recently returned from Kazakhstan. Someone came from the Kazakh embassy to say how important Peace Corps was to Kazakhstan.

This was the first chance the volunteers had to meet the rest of the group which numbered 28. My initial impression was I that had little in common with the rest of the group. It wasn't a question of age. The average age was probably around 32 and here were also two other over 60s in the group. Eleven had M.A.s. It was more a question of attitude. I saw self important alpha types who were now going to put things right in Kazakhstan. At one stage in the orientation, everyone was asked whey they had joined Peace Corps. "Show me the pit toilet." said one. "My whole life is in two bags." said another. I sensed from the answers nothing of the goodwill spirit I had been expecting or even a genuine curiosity in the Kazakh people.

We flew via Frankfurt, Germany and arrived around 3 a.m. in Almaty, Kazakhstan's largest city and then capital (until it was later moved to Astana). At that hour in the morning there was no delay in getting through immigration. While we were waiting for our bags to appear, a blond-haired alert woman appeared and introduced herself as Kris Besch. She was the country director. To me she said: "I know you have written three guidebooks, I hope your experience will help us here." After a token customs inspection, we lugged our bags and laptops (just about everyone had one) outside where a group of current Peace Corps volunteers welcomed us and shook our hands. The weather was biting cold, and there was snow on the ground.

Three months of training followed. We were taken to a small town called Issik twenty miles from Almaty, where we were put with private families and used a local school as our classroom. Here we met the Peace Corps staff, a group of able Kazakhs whose job was to prepare us for two years in-country when we would be on our own.

I hated the time spent training. The training schedule lasted three months and consisted of daily Russian language lessons and also talks on Kazakh culture and health issues. It was late February and still winter. The school was not well heated, and we all wore overcoats in the classrooms. Our teacher was a competent and attractive Yughur in her forties called Guzel but our progress went at the speed of the slowest learner. During breaks I found I had little to say to my fellow students.

I was placed in an apartment of an older widowed lady called Myra whose husband had been a professor. She was a warm and welcoming person always anxious that I was comfortable. I had my own room, and the apartment was well heated. There was TV and a bathroom with a tub. Myra cooked well and was always happy when I ate a lot. She encouraged me to speak more Russian but, since she spoke German and so did I, I tended to take the easy way and we spoke in German much of the time.

Walking to the school from my lodging meant slipping and sliding on potholed streets which had not been cleared of snow and ice. There were some traditional, pleasant-looking small houses with gardens in the town, but most of the public buildings and apartment blocks were drab, grey in color and needing maintenance work. The local market and the bus station were the only places that had some life. It took me 30 minutes to walk to the school, or I could catch a ride. Drivers of private cars accepted paying passengers so I just stood at the roadside and waved at any passing car to stop, then agreed the fare.

During our time off, we took trips into Almaty as a group or on our own. Before leaving Texas, I had been given the name of a Kazakh family in Almaty. The father had been an academic and an important figure in the Communist party. Two sons were doing well in an economy which was evolving from communist to partial capitalist, with corruption being the main factor. I contacted them and was immediately invited to their home, an apartment in a modern building.

The family was kind and thoughtful, inviting me out for meals and showing me the sights of Almaty. Nine months later, when I arrived back from a Christmas vacation trip to London with an unmanageable load of saddles and bridles for "Wild Nature," my host organization, the sons saved my bacon. Responding to a desperate email from me, they met me at the airport, and transported the unwieldy tack by car to their apartment. They fed me a meal, then took me to the train station and loaded everything onto the train I was taking to my village.

My fellow volunteers were adapting according to their commitment and abilities. We had lost two after three months: one, a lawyer, was sent back to the USA as a wrong choice. The other, an older woman, could not cope with the primitive living conditions. Everyone else was making some sort of progress with the language, and anxious to get to their destination to start the real work.

Peace Corps made a big show out of the graduation process. First there was a performance at the school by all volunteers, as a thank you to the families who had hosted us, and also for the hosts of the institutions or business which were about to accept us to work with them. Then we were taken to a public meeting room in Almaty where the American ambassador formally enrolled us into Peace Corps. This was followed by a buffet meal.

Some of the group wanted to go out drinking, but I headed back to the bus station to catch a ride back to Issik. I was walking down a main street, along a broad pavement, when a young guy overtook me. As he passed he pointed to what looked like a wallet lying on the pavement. He pointed at it, then enquiringly glanced at me saying, in effect: "Should I pick this up? Should we share the contents?" I shrugged and walked on.

A block later, an angry man confronted on the sidewalk showing me an empty wallet. It looks like the wallet that the other fellow had just picked up. The man in front of me was gesturing, threatening perhaps, and seemed to be suggesting I owe him money. I ignored him and walked on. He followed me for a while shouting but then broke off. Later I found out that this was a local scam, enticing a stranger to share in stolen goods, and then confronting him to get a pay off to prevent him from going to the police. Fortunately I had not participated, so I felt no involvement. It was the last thing I expected just having participated in Peace Corps graduation.

Because of my background in tourism, I got a choice location when assignments were announced. This was with a Non Governmental Organization called "Wild Nature" which was developing a green tourism program in a village called Aksu Zhabagly in the south of Kazakhstan. Close to the Tien Shen range (an extension of the Himalayas), the village contained the headquarters of the oldest national park in central Asia which started just north of the village and encompassed 503 square miles.

"Wild Nature" NGO was the brain child of two Russian wildlife biologists, Svetlana Baskakova and Vladimir Shakula, who had stayed on in Kazakhstan after the split up of the Soviet Union. They were working on a shoestring budget out of their house in Aksu Zhabagly, dependent on income from tourists to survive. They were hoping that a Peace Corps volunteer would help them develop their services, and market them to a wider public. That was my job.

The village of Aksu Zhabagly was one long street bordered by small houses. All had electricity. A mile away the flat steppe gives way to the foothills of the Tien Shan mountains. Snow lay on the highest peaks year-round. This was glorious scenery. Along the main street were a mosque, attended by just a few old men, a three story school with flaking paint and a village store. 800 people lived here. Minibuses waited at one end of the street, and when full, departed for Tyulkubas, the nearest town.

SVETLANA’S CHILDREN

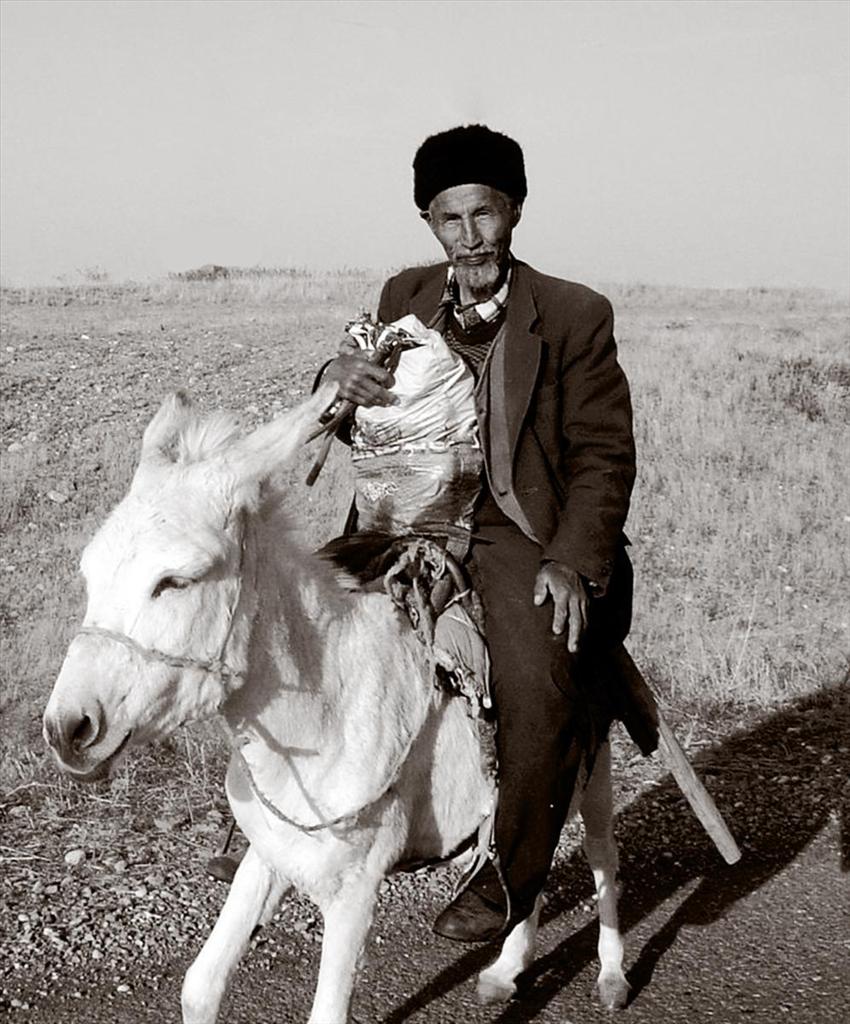

OLD MAN ON DONKEY

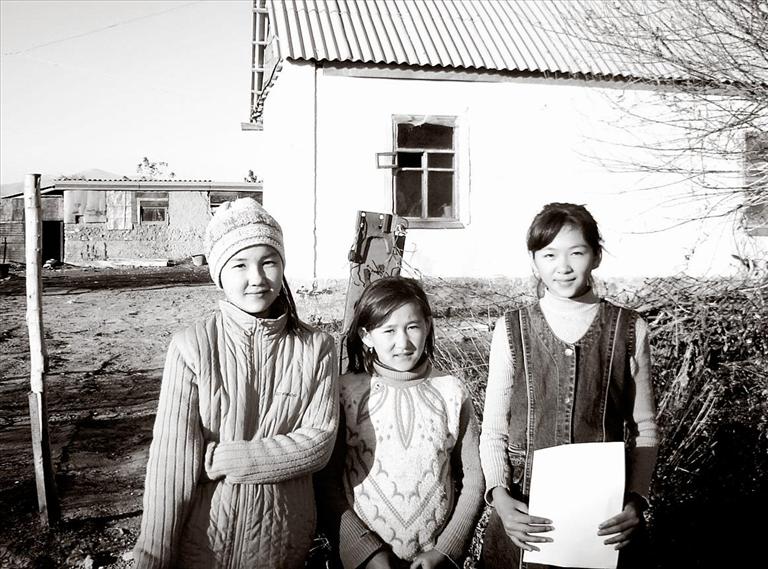

KAZAKH CHILDREN

TOURISM HOST FAMILY, ZHABAGLY

I was given a room in a one-story house with a large orchard. The husband did occasional farm work and looked after the orchard; the wife was a teacher. Their youngest daughter still lived at home, a shy fourteen-year- old who spoke good English. The house had heating, and there was a banya shed (sauna) outside where I took a weekly wash. The house also had a phone so I could get dial-up internet connection on my laptop. This was a comfortable place given the conditions in the village, and I got on well with the family.