Fordlandia (21 page)

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

On October 4, the plantation’s representative in Belém cabled Charles Sorensen in Dearborn good news: “

Lake Ormoc

left Santarém last night bound for plantation.” But later that day he sent a correction: “Report

Ormoc

leaving Santarém for plantation in error due to misunderstanding.

Ormoc

still at Santarém.” Then a third: “Water going down instead of rising.”

17

At the end of November, there were still over a thousand tons of equipment on the

Farge

, and the general chaos of the work got on the crew’s nerves, yielding to “nasty accidents” and scuffles. On the last day of the cargo transfer, “Sailor Stadish” was on the deck of the

Ormoc

operating a steam winch and teasing “Fireman Patrick,” who was in the hold supervising local workers in a final cleanup. Stadish said something he shouldn’t have, or at least not to someone in the hold of a ship on a day when the thermometer had well passed ninety degrees. He looked up and saw Patrick coming after him with an iron bar. Taking a step back, Stadish fell into an open hatch twenty-five feet, fracturing his skull and breaking a few ribs.

18

It was not an auspicious beginning for a company that hoped to, as Edsel Ford put it, bring “redemption” to the Amazon. It took nearly until the end of January to finally get the ships up to Boa Vista and fully unloaded. And then the trouble really began.

____________

*

Though an improbable amount, both the

Times

and the

Los Angeles Times

reported this six billion figure, most likely provided by a company press release.

*

It was Spruce who identified and delivered to London a potent variety of cinchona, used to begin cultivation in India to make quinine—described by one official with the East India Company in 1852 as the most valuable medicinal drug in the world, “with probably the single exception of opium.” At Santarém, where Spruce lived for over a year, he documented the local use of guarana—a caffeinelike stimulant prescribed for nervous disorders and thought to be a prophylactic for a variety of diseases—believing it could be introduced into European pharmacies, perhaps as a supplement to tea or coffee (Mark Honigsbaum,

The Fever Trail: In Search of the Cure for Malaria

, London: Macmillan, 2003, p. 5; Richard Spruce,

Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon & Andes: Being Records of Travel on the Amazon and Its Tributaries

, London: Macmillan, 1908, p. 452).

CHAPTER 10

SMOKE AND ASH

AS THEY WAITED FOR THE

ORMOC

AND THE

FARGE

TO REACH THEM, Blakeley and Villares set about establishing a work camp just outside the hamlet of Boa Vista and started to clear the jungle. True to the kind of optimism typical of the Ford Motor Company in the 1920s, reinforced by Villares’s constant assurances that he had plantation experience, Blakeley was convinced that the rain forest and its people would soon yield to a “great industrial city” housing twenty-five thousand workers and a hundred thousand residents. The proposed location for this metropolis, on a rise sloping gently to the river, “lends itself well to an economical development of sewage.” Though Blakeley was no more an engineer than his immediate boss, Harry Bennett, he thought building a city would be “a more or less simple matter.” His plan was to allow arriving workers to live in temporary quarters set apart from the main settlement, until pronounced fit by Ford doctors to move into Fordlandia proper. Under company supervision, Brazilians, Blakeley proposed, should be allowed to build their own homes according to local traditions, though he would insist on the construction of proper and sanitary outhouses, which would be an important step in bringing “forth a new race.” He told the American consul in Belém that Ford had given him “carte blanche” to spend up to twelve million dollars, not just to “show some profit for the company” but to “do good” for the Amazon.

1

In a preliminary report to Dearborn, he suggested paying workers between twenty-five and fifty cents a day and teaching them how to grow vegetable and fruit gardens to diversify their diet. Schools and churches would be built later, as the tappers were long used to living and working in isolation, free from religious and educational institutions. Unlike at the Rouge, he did not foresee a discipline problem; Brazilian workers are “most docile,” he wrote. Among his crew, he hadn’t heard the “slightest murmur of Bolshevism.” Not even the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti—which took place just as he and Ide were negotiating the concession with Bentes—aroused their sympathy, Blakeley said.

2

Yet also true to the Ford tradition, Blakeley quickly developed a reputation as an autocrat. During his short reign at Fordlandia “his word was law.” He had set himself up in an old Boa Vista

fazenda

—Portuguese for hacienda—that was decrepit but well ventilated while the laborers slept outdoors in hammocks or in palm lean-tos and his foremen crammed into a quickly erected, sweltering, malaria-ridden bunkhouse, each given “one room with one door and no window and no bath.” Dearborn first got an inkling that something was wrong when Blakeley tried to take control of the subsidiary corporation Ide had set up as the legal owner of the plantation. “You have not explained why,” company officials wrote him pointedly, “it was necessary to elect yourself managing director.”

3

But where autocracy in other realms of the Ford empire tended to produce some concordance between vision and execution, in the jungle it led to disaster.

THE FORD MOTOR Company enjoyed a well-deserved reputation for industrial immaculateness. Hundreds of workers painted the Detroit plants on a regular basis. Cleaners scrubbed them as if they were operating rooms, making sure even the most remote corners were well lit, to prevent spitting. “One cannot have morale,” Ford said, “without cleanliness.”

4

Imagine, then, Dearborn’s reception of this very first notice on Fordlandia’s progress: “No sanitation, no garbage cans, flies by the million, all filth, banana peels, orange rinds and dishwater thrown right out on the ground. . . . About 30 men sick out of 104, no deaths but plenty of malaria. . . . Flies abounded in kitchen in all food and on tables and dishes until you could hardly see the food and tables. No screens for men to sleep under, no nets.” The report was filed by São Paulo’s Ford dealer, Kristian Orberg, after a visit to the camp. Orberg told Dearborn that two creeks bordering the main work site had been converted to a dump, breeding flies and mosquitoes that led to a severe outbreak of malaria. As a result, work came to a standstill for nearly the whole month of August. Food rotted. “They need ICE worst of all,” he said.

The impending arrival of the

Ormoc

and

Farge

promised tractors and other heavy equipment that would ease the work involved in land clearing. But in the meantime Blakeley and Villares tried to make do. In Belém, Blakeley had purchased a few power saws and a small tractor, which he had delivered to the work site. Yet he quickly ran out of gas, so the machines sat idle. After months of labor, with workers cutting and dragging logs by hand, only a few hundred acres of trees had been felled.

To add to the difficulties, the two men had picked the wrong time of the year to begin work. Ideally, the clearing of jungle for planting or pasture should be done during the dry season, between June and October, when the downed trees can be left to dry for a few months before being burned. But Blakeley and Villares had started felling trees during the wet season. When they tried to torch the waste wood, daily rains would extinguish the fire, leaving soaked piles of charred scrub. So they had to use copious amounts of kerosene to start a second burn, bigger than any yet seen on the Tapajós—or in most other parts of the Amazon, for that matter. The jungle was turned inside out, as flames rose over a hundred feet, forcing tapirs, boars, cougars, boas, pit vipers, and other animals into the open, “crying, screaming, or bellowing with terror.” Toucans, macaws, and parrots took flight, some of them falling back into the flames.

5

“They burned hundreds of hectares of primitive forest,” remembers Eimar Franco, who watched the progress of Fordlandia from across the river. “They started a fire that lasted for days and days,” he remembers, invoking both an image associated with today’s Amazon—the forest laid waste by fire—and the smokestack and forge fires of nineteenth-century factory industrialization: “It terrified me. It seemed that the whole world was being consumed by flames. A great quantity of smoke rose to the sky, covering the sun and turning it red and dull. All that smoke and ash floated through the landscape, making it extremely frightening and oppressive. We were three kilometers away, on the other side of the river, and yet ash and burning leaves fell on our house.”

6

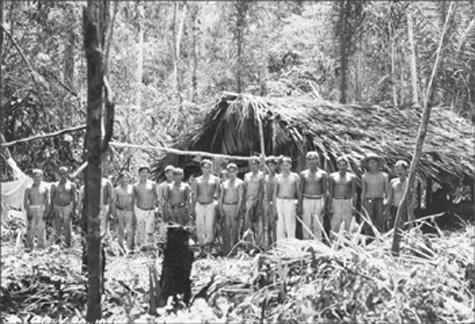

Charred trunks and stumps after an incomplete burn

.

DEARBORN WAS GROWING increasingly distrustful of Blakeley. No archival evidence proves that Blakeley took a profit from the machinations surrounding the Bentes concession, yet the fact that he kept his dealings with Villares, Greite, and Bentes, as well as his knowledge of kickbacks, a secret couldn’t have sat well with Henry Ford, who learned about the swindle from State Department officials in early 1928.

7

For Blakeley’s part, whatever opportunities he saw arising from Ford’s rubber enterprise were fanned by a growing sense of grievance. He began to resent the fact that the company was not rewarding all his good work with adequate compensation, and he sent Charles Sorensen a letter asking that his salary be increased to “A” level. His long stays in Brazil, he complained, had forced him to sell his Dearborn house and lose track of his investments. He reminded Sorensen that he had given up much American-style pleasure and comfort in order to “accomplish things in a country such as this.” He began to pocket plantation cash, money that should have been used to buy quinine for the fever-ridden or gas for the power saw and tractor. He even refused to buy a horse for the fifty-four-year-old Raimundo Monteiro da Costa, a local rubber man hired to scout out the concession. During the hottest part of the day, the “old man” was making two four-mile tours on foot. And though Blakeley promised workers free room and board, he deducted the cost of transportation to the site from their first payment and charged them forty milreis, about four dollars, for hammocks that cost half that. Dearborn didn’t get wind of this petty graft until much later, yet in July a witness had emerged, a fellow passenger on the SS

Cuthbert

, who supported Ide’s account of Blakeley’s coarse behavior “in every particular.”

8

Dearborn recalled Blakeley and dismissed him in October, and his sudden departure led to a collapse of what little authority there was at the work camp. The remaining Americans bickered among themselves. Villares tried to leverage the bedlam to his advantage. No one was clearly in charge, so no one took responsibility for feeding and paying the camp’s labor force, which had grown to 380 men. A month of bad food, no money, long workdays, and increasingly insulting behavior by increasingly desperate foremen were aggravated by a heat wave that made the jungle hotter than usual.

In the best of conditions, clearing jungle is brutal, close-in work. But as October ran into November, high temperatures were hitting 106 degrees. Exhaustion and sickness overcame the contracted laborers who made up Fordlandia’s first crew as they hacked their way into the dense, dank wood with machetes and cutlasses. They worked stripped to the waist: throughout the day, as the sun rose and the humidity increased, their bodies, covered with sweat, were scraped by thorns and branches and punctured by the bites of ticks, jiggers, black flies, and ants. The workers were not provided hats though these were indispensable when making the first pass at jungle clearing, as often the chopping of a creeper or a vine could disturb insect nests, raining scorpions, wasps, or hornets on those below. Just a touch of a branch or a vine and within seconds a swarm of ants could cover a body, leaving workers red with festering bites. The mortality rate was high, as workers, bending low to chop the undergrowth, died quickly from snakebites or suffered a more prolonged wasting away from fever, infection, or dysentery.