Fordlandia (28 page)

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

Charles Sorensen—handsome as Adonis, thought a colleague, and “masculine energy incarnate,” wrote a historian—started out working at Ford’s foundry pattern shop in the old Highland Park plant. By the 1920s, his engineering intelligence had combusted with a “burning passion for advancement” to catapult him to the pinnacle of company power. Sorensen jockeyed for position with Ford’s other lieutenants, including Edsel Ford and Harry Bennett, and became the executive force behind Rouge production, as well as assuming a large role in the running of Fordlandia.

2

Others who didn’t make it that high nonetheless had new vistas opened to them. Victor Perini, a twenty-year-old son of Sicilian peasant immigrants, was apprenticing as a toolmaker with the Richardson Scale Company in Passaic, New Jersey, when he heard from a friend that the Ford Motor Company needed workers. So he and his wife, Constance, headed for Detroit. It was 1910, and the company was still operating out of its first plant on Piquette Avenue, then producing a hundred Model Ts a day.

“Can you use a toolmaker?” Victor yelled through the plant’s gates. “Oh yes, we can use a toolmaker,” came the answer. He was hired at thirty-five cents an hour.

3

As Perini’s engineering know-how matured into a reserved yet meticulously observant managerial style, he was promoted to help run Ford’s copper radiator factory and hydroelectric dam on Green Island, in the Hudson River near Troy, New York, then sent to Manchester, England, where he oversaw the manufacture of the British Model T, and on to Iron Mountain, where he built an airstrip before becoming manager of Ford’s state-of-the-art sawmill.

“We covered a lot of places during the years that my husband was at Ford’s,” Constance recalled of Victor’s career. “The company was more than generous in arranging accommodations for our comfort and convenience. We always went first class.” She remembered with gratitude that “because of this the entire family has had experiences that are not often duplicated.” But there was one not-so-comfortable place Ford sent them.

VICTOR FIRST LEARNED about Fordlandia from Henry Ford himself, when his boss visited the Perinis at their home in Iron Mountain in late 1929. “You would think that he owned everything around here,” said Henry to Constance as he surveyed the photographs of Ford factories that hung on their living room wall. Over their kitchen table, Ford, having himself been recently debriefed by Cowling, told Victor about the mess Oxholm had made of things in Brazil and asked him to check on the sea captain and relieve him of his duties if necessary. Perini immediately said yes.

The first thing Perini did was tap other workers he wanted to bring with him, and he did so with the same kind of informality that got him his first Piquette Avenue job. One morning a few weeks after Ford’s visit to his home, Perini, along with another Iron Mountain manager named Jack Doyle, ran into the tousle-haired second-generation Irish sawyer Matt Mulrooney on his way to work.

4

“What would you give for a good job, Mulrooney?” asked Doyle.

“A cigar,” Mulrooney responded without missing a beat.

“Come on and give it to me.”

“I haven’t got the cigar on me. Mr. Perini, you’ve got some in your pocket. Lend me one.”

Perini did and Mulrooney handed it to Doyle, who “sprung this proposition” on him “about going to South America.”

“What do you say?” they asked the sawyer.

“I haven’t got anything to say. If I’m of more use to the company down there than I am here, I’d be a damn poor stick if I wouldn’t go. They’ve been feeding me here quite a while. It would be a good thing to go down there and eat off them for a while.”

“Well, that’s pretty good,” said Perini, who later described Mulrooney as a “gentlemanly young man.”

“Don’t say anything about it now for a while,” Perini told his recruit, “later on, we’ll see.”

Mulrooney proved more obliging than did Perini’s wife. Constance was tired of packing up house as they moved from one post to another and wanted to “live at the same number on the street” for just a bit longer. “You go by yourself this time,” she told her husband.

“Okay, you can stay here,” Victor said. But Ford overruled him. Dearborn had by then received word that the drinking and gambling of Fordlandia managers was mitigated somewhat by the “presence of American women.” Wives were having a “beneficial effect on the general appearance of all the men here,” a Fordlandia manager wrote. Even the “whiskermania” that had gripped Americans cut free from Michigan’s clean-shaven decorum waned in their presence. Ford’s men and machines would civilize the Amazon, but Ford’s women were needed to civilize his men.

5

“Where you go,” Ford told Perini when the two men met later in Dearborn to discuss specifics, “your family goes with you.” Victor nodded and phoned Constance back in Iron Mountain. “I guess you better get ready.”

THE PERINIS’ TRIP, in early March, was nothing like Ide and Blakeley’s gentle roll to Belém two years earlier. Off the coast of Florida, the

Ormoc

ran into a hurricane. Lashing rain drenched the ship, whose motors were no match for the whitecaps washing over its deck. Unable to make steerageway, the boat drifted hundreds of miles into the Atlantic. Pitching and rolling “all day and night,” the

Ormoc

tossed cargo into the sea as the passengers huddled in their cabins.

The Perini family

.

It took two days for the ship to right its course, and another two weeks to arrive in Belém. The Perinis and their three children stayed at the Grande Hotel, which was the best in the city yet still a place where spiders could be found in the bedclothes. Belém’s Ford agent, James Kennedy, told Constance to get used to it. In the Amazon, he said, “the cockroaches follow the ants, and the mice follow the cockroaches. Everything takes care of itself, don’t worry about it.”

After a rough night in a soft bed, which gave out under Victor’s weight, the Perinis were “glad to get back on the

Ormoc

because it was nice and clean there, even though traveling was rough.” Both the Amazon and the Tapajós are broad rivers, in places vastly so. In a work published just that year, the Brazilian writer José Maria Ferreira de Castro noted that the Amazon makes perspective impossible. Instead of appreciating its vast panorama, first-time observers “recoil sharply under the overpowering sensation of the absolute which seems to have presided over the formation of that world.” And as the Perinis made their way up to the plantation, the wide sky combined with long stretches of dense forest to weigh on Victor’s mind. He complained of the tedium as they passed endless low banks with “no hills of any kind and nothing but trees and vines visible.” The view was interrupted only by occasional villages, most derelict and some deserted. The family was traveling during the rainy season, when the Amazon just below Santarém is at its widest and the constant green of the shore at its most distant. During these months, the floodplain spills over into the forest, creating half-submerged islands and a “vast flow of muddy water,” as the writer Roy Nash, who made the trip just a few years before, described his impression. Sailing as close up the middle of the waterway as possible, voyagers on oceangoing ships often miss the sublime, radiant sensation many experience under the rain forest canopy; traveling on a crowded boat, wrote Nash, one is even cheated of the “poignancy of solitude.”

*

After leaving Santarém, the

Ormoc

’s captain, unfamiliar with the Tapajós’s shifting channels that make it difficult to travel even when the water is high, ran the ship aground and was pulled free by a tug only after “considerable effort.”

6

Victor was even less taken with Fordlandia, and whatever recoil he might have felt on his voyage from the human emptiness of the jungle was intensified when he confronted the amount of work the place needed. His first impression upon leaving the dock was of tractors and trucks “wailing in mud,” slipping and sliding on roads that weren’t graded, drained, or surfaced properly. The rain was constant, and the wet heat, without the relief of a river breeze, overpowering. “There is so much to be done that it looks hard to decide where to start. . . . It will be necessary,” he thought, “to start a railroad line at once,” along with houses, schools, and a receiving building.

7

DESPITE PERINI’S INITIAL impression, and despite first Blakeley’s and then Oxholm’s clumsy administration, Cowling’s lecture had had a galvanizing effect on Fordlandia’s managers and the project of transforming the jungle into a settlement and plantation had advanced considerably. The labor situation had stabilized somewhat, and by the end of 1930 Fordlandia employed nearly four thousand people, most of them migrants from the poverty- and drought-stricken northeast states of Maranhão and Ceará. Before he departed, Cowling delegated more authority to the engineer Archilaus Weeks, who had arrived in Fordlandia in 1929 from Ford’s L’Anse lumber mill, located on Lake Superior in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, to take charge of construction.

8

Under Weeks’s direction, a recognizable town had begun to take shape along the Tapajós to replace Blakeley’s work camp. Having pulled up the stumps and burned the undergrowth along the river frontage, Weeks organized a more efficient system to receive material and process potential employees. Workers had begun to lay pipes and wires for water, sewage, and electric systems. The sawmill and powerhouse had been completed, and the water tower was rising. About thirty miles of roads crisscrossed the property, pushing into the jungle. Work was under way on a 3,200-square-foot dining hall to replace the shambles of a mess hall left by Blakeley. The old lopsided hospital was torn down, and in its place was built a sleek new clinic designed by Albert Kahn. And soon after his arrival, Perini took charge of supervising the construction of what would be a three-mile-long railroad, cutting through the estate’s many hills and linking the sawmill to the farthermost field camps, which were charged with clearing more land for rubber planting.

9

Dearborn had also finally sent a topographer down to do a proper survey and identify the best location for a “city of at least 10,000 people to cover about three square miles.” Though Fordlandia was going on its third year, the construction of permanent houses for its Brazilian workers had not yet begun. Single laborers lived in bunkhouses or in holdout towns like Pau d’Agua along the plantation’s periphery. A few took up residence across the river, on Urucurituba island, and paddled to work every morning. Married workers mostly lived in the ever metastasizing “native village” stretching along the river. The largest, rambling part of this settlement was made up of the families of the plantation’s common laborers. They slept and cooked in one-room thatch houses, some of them reinforced with planks pried off discarded packing crates. Children, mothers, fathers, and other relatives hung their hammocks like radiating spokes from a central pole; the cooking fire’s smoke damaged their lungs but protected them from mosquitoes. Better-paid workers—hospital orderlies, coffee roasters, cooks and their helpers, waiters, log loaders, swampers, deckmen, firemen, gardeners, painters, oilers, janitors, sweepers, clerks, bookkeepers, stenographers, teachers for the Brazilian children’s school, draftsmen, boat pilots, meatcutters, tinsmiths, and blacksmiths—lived in slightly nicer houses, often made of milled wood, but also with thatched roofs and dirt floors. As the workforce increased, the town grew haphazardly, with packing crate planks recycled as boardwalks, laid over a midway that turned to mud in the rain and baked into ruts in the sun.

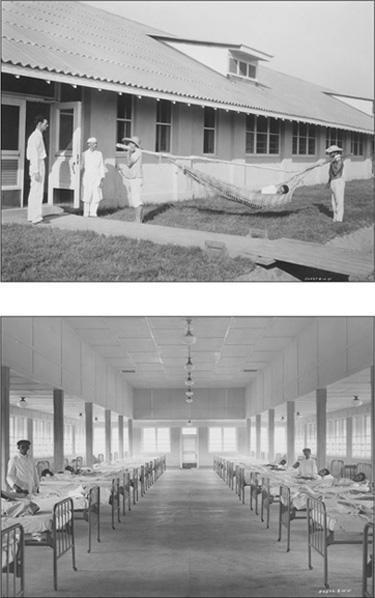

Top: An “ambulance” arrives at Fordlandia’s hospital, designed by Albert Kahn. Below: The scene in the hospital ward

.

By 1930, the plantation’s lines of administration had evolved into a more or less settled routine. Oxholm, who either decided or was told to leave the plantation two months after Perini’s arrival, was still the nominal manager, yet work was organized through a number of departments: “plantation,” “gardens,” “construction,” “sawmill,” “transportation,” “general stores,” “kitchens,” “clerical,” and “medical.” Americans, Europeans, and skilled Brazilians presided as managers and assistant foremen over work gangs of Brazilian laborers, who mostly remained nameless as far as company records were concerned so long as they didn’t try to organize a union, steal, or cause some other kind of trouble. Archie Weeks oversaw the largest part of the labor force, the men who did the hardest, most exhausting, and often deadliest work, beating back the jungle, quarrying stone, cutting underbrush, sawing trees, burning the wood waste, tilling the ash and soil, and planting new blocks of rubber. Weeks developed a “rare knack of training the natives to do his work,” according to his personnel file. He was a “driver,” but in a way that “made his men like it,” which may very well have been the case since most credited him with whatever progress Perini saw upon his arrival.