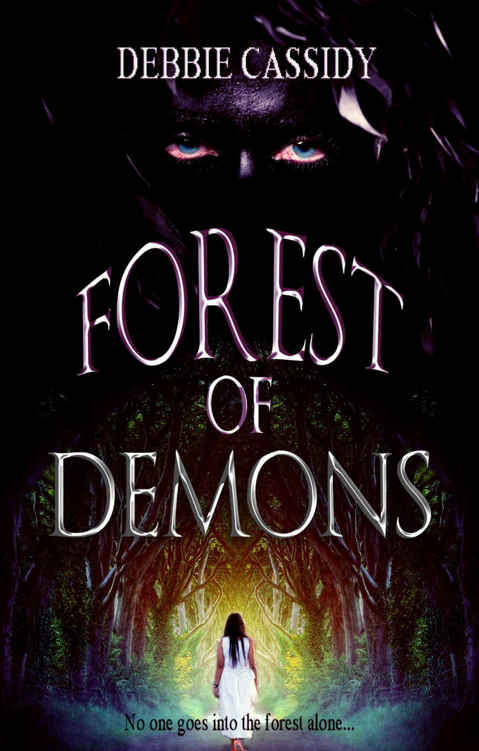

Forest of Demons

Authors: Debbie Cassidy

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, events, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

No part of this work may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher.

Published by Kindle Press, Seattle, 2016

A

Kindle Scout

selection

Amazon, the Amazon logo, Kindle Scout, and Kindle Press are trademarks of

Amazon.com

, Inc., or its affiliates.

This one’s for you, Dad.

Love you so much, and miss you every day.

Authors Preface

Forest of Demons was inspired by my dad’s love of Hindu mythology. He urged me on many occasions to learn more about the mythology that was integral to my Hindu culture, but I always made an excuse not to. When we discovered he was sick, I found myself compelled to finally pick up some books and do some reading on Hindu mythology and culture. Before I knew it I was inspired. A fantasy world began to grow in my head; one which incorporated the mythology, 18th Century Hindu culture, and terminology but wasn’t set in any real world. Two Isles separated by oceans and magic, two cultures, two very different main characters ... What would happen if these worlds collided? I wrote the first draft of Forest of Demons in a frenzy, creating a fictional world that existed out of our time, whose rules are still unfurling, even for me its creator. I was lucky enough to be able to share the first draft with my dad before he passed away. I can’t help but wish he was here now to see it published, but I believe that he’s watching over me, and I know he’d be so very proud.

Isle of the Red Sun

“Tradition becomes our security, and when the mind is secure it is in decay.”

—Jiddu Khrisnamurti

Branches lashed at her face, tangling in her hair and yanking it out of its plait. She focused her every breath on catapulting down the trail, with nothing left for screaming, for calling for help. They were behind her – she could feel them. One, two, maybe more, she wasn’t sure, and it didn’t matter. All that mattered was the trail.

This shouldn’t be happening when the sun was high.

Surya

time was safe. During Surya time, the sun burned their hides and rendered them blind.

Her heart pounded. Her foot tangled in a root, and she stumbled, righted herself, and kept running.

Stupid, stupid, she’d been so stupid.

But then the trail widened. Her heart lifted with hope. She was almost home.

They came from the side, hitting her hard and taking her down. Her nails raked earth as they dragged her backward, her final, bloodcurdling scream cut off as they tore out her throat.

Priya hoisted the large

matka

filled with water over the threshold of her hut. The water in the large urn sloshed onto the floor, and she cursed under her breath. Her ankle-length skirt caught on one of the long iron nails hammered into the sides of the threshold; she cursed again as she ripped it free and stumbled into the kitchen.

Ma looked up from the stove where she was cooking

chapatis

. Priya sighed at the sight of the traditional flatbreads. Lord, what she wouldn’t give for some fluffy white bread like Mala and her family baked. They would dip it in thick, fragrant meat stew and—

“Stop dreaming, child, and bring it in.” Ma ushered her in, pointing to the clothes basin. “Clothes won’t wash themselves.”

If only.

She did as she was told and filled the basin with water, grabbed the washboard and soap, and began to lather up. “Why can’t I just do this at the river like everyone else?”

“Because I don’t want your head filled with nonsense. Goodness, the gossip of those women, it’s enough to give you earache.”

“I would gladly put up with earache simply not to have to make two trips to the well.”

Ma brandished her chopping knife in Priya’s direction. “Hush your moaning. At this rate the sun will have set by the time those clothes are washed.”

Priya knew when she was beaten. The gossip of the river would have to remain a mystery for a little while longer. She washed while Ma cooked, and for a time they worked in companionable silence. The smell of potato and eggplant curry filled the small space, and despite her irritation with their vegetarian diet, Priya’s mouth began to water.

She’d just finished the last tunic and was gathering the clothes to hang out to dry when the silence was filled with the toll of a bell.

They exchanged shocked glances. The bell hadn’t been used for at least a year, maybe more.

Dropping the clothes, Priya ran out of the hut and into the square where people had already begun to gather. They looked dazed and uncertain as to why they had been summoned, even though it should have been obvious.

The bell meant death.

The bell meant

rakshasas

They ate in silence. Priya’s eyes were gritty and swollen from crying, and Ma kept shooting her concerned glances. Papa was solemn. He’d come across the remains while searching for roots and medicinal herbs in the forest in his role as the village

villee

. At first he’d been confused, unsure of what he saw, but then he’d seen the jewelry. The village police inspector had used that to identify her. The demonic rakshasas weren’t bothered with gold and gems—they craved flesh, and of that they’d left little.

Priya choked on her food and took a gulp of water.

“

Beti

, are you all right?” Ma asked.

“Of course she’s not all right,” Papa said. “This is unprecedented. It was surya time.” He tutted. “Poor girl. Her parents are devastated, and Guru . . . he’s inconsolable.”

The name of Mala’s betrothed brought a wave of mixed emotions. Priya swallowed the lump in her throat. “May I be excused?”

“You’ve hardly eaten anything,” Ma chided, but there was concern in her reproach.

“Leave the girl. Go, beti. Go rest,” Papa said, waving her off.

Priya uncurled her legs from under her, stood, and escaped to her tiny room at the back of the hut.

She lay on her narrow bed and listened to her parents speak in hushed whispers. Ma worried that Papa had lost a whole day of work. The villagers paid in grain for the herbs, roots, and fruit he gathered from the forest, but the majority of his finds went straight to the

vythian

, the village doctor, for use on the sick and ailing. Unlike other able-bodied men, Papa was unable to work in the fields for the

zameendar

. Papa’s damaged leg wasn’t strong enough to handle field labor for a landowner, so he paid for his portion of grain by filling a slightly more dangerous role. Every day he went into the forest, he risked a rakshasa attack.

Like the one today.

She reached out and traced the words etched into the wall by her bed: Mala, Guru, and Priya. She remembered clearly the day they’d defaced the wall. It had been her eighth birthday. Ma had made a real birthday cake, just like the ones Mala always had, and Mala and Guru had been allowed to sleep over for the night. Ma had made it clear that this would be Guru’s last sleepover. She’d said that soon he’d be a man. Priya recalled looking at him, a skinny boy with floppy hair and a cowlick at the top of his head, and wondering how he could ever be a man like Papa, who was tall and broad with whiskers on his chin. That night they made a pact: No matter what happened they would be friends forever. The etching had been a promise. Even Mala’s betrothal to Guru, although it had hurt, did little to diminish their closeness. But now Mala was dead.

Priya covered Mala’s name with the palm of her hand, tears snaking down her cheeks. “Sorry,” she whispered. “I’m so sorry.” She turned her back on the wall and closed her stinging eyes. One question drifted through her exhausted mind before sleep pulled her under: What had Mala been doing in the forest alone?

The next morning Priya rose at dawn as usual. After washing and lighting the prayer incense, she lit the cooker by stoking the fire underneath. She put water on to boil for tea before rousing Ma and Papa. While they dressed and prayed, she made tea and unwrapped some savory breakfast biscuits.

Breakfast was always a quick, quiet affair; there was always so much to do—chores and more chores, all day long. She missed the school days when Master Munim would walk up and down the neatly arranged rows of children, slapping his cane in his palm and glaring at them over the tops of his half-moon spectacles.

School days had been over for years, and now at nineteen, Priya was almost an old maid. It had been all right for Mala; she’d been younger by two years and still at an acceptable marriageable age. The thought of Priya’s dead friend brought a fresh wave of grief. She swallowed it with her tea and gathered the cups for washing.

“Beti, can you help Papa in the market today? His leg is acting up.”

Priya perked up. The market was a much better prospect than household chores, but one look at her frail mother and she was riddled with guilt.

“Let me fetch water first and feed the chickens and milk the cows.”

Ma shook her head. “No time. The sun’s up and morning prayers will be over. The stall needs putting up.”

Priya was already at the door with the bucket. “Then let me fetch water at least. I’ll be quick.” She didn’t wait for permission, but rushed through the village to the well. There was already a queue, and she waited impatiently, tapping her foot.

Nita and Miriam stood at the front of the queue, chatting. Nita worked for the

munsiff

of the village, and Miriam was the

pujari’s

wife. Because of their close associations with the village’s major and priest, they were both high-ranking women in the community, which explained why no one was urging them to wrap up their conversation and be on their way. Priya gnawed on her bottom lip. Up ahead she could see other traders already setting up their stalls. The barber had even claimed his first customer of the day. Being late meant loss of business. Papa grew the best tomatoes and eggplants, healthy and large, and Ma created the most beautiful pots and vases. But if he were late to display his wares, then one of the other sellers would get the business.

She craned her neck to look at Nita and Miriam. Nita had already filled her matka and had it balanced on her hip. They were laughing, completely indifferent to the other women queuing for water.

Taking a deep breath, Priya called out, “Excuse me? Nitaji, Miriamji, will you be much longer?” She was careful to add the required ‘ji’ to their names when addressing them, as a mark of respect for their status in the community.

The women stopped talking and turned to look at her, sizing her up as if she were an annoying gnat.

“Who is that?” asked Nita as if she didn’t already know. Being the village gossip meant she was a walking directory of information.

“It’s Priya, the villee’s daughter,” Miriam said.