Forever Barbie (31 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

Some artists have used the dolls to make personal rather than political statements. Roger Braimon, who received an M.F.A.

in painting from the University of Pennsylvania in 1992, used Ken and Ken-like dolls for a series of representational paintings

stylistically evocative of the work of fidouard Manet. Although the dolls are fully dressed and their poses not sexually explicit,

the paintings have a powerful homoerotic charge—in part because of a narrative element he repeated in the images, what he

terms the "glossy decapitated portrait of a hunky male" that is packaged with Calvin Klein underwear.

"Coming out in my second year of graduate school was a big thing for me," Braimon told me. "I was comfortable with it—but

not in my painting. So these Ken dolls were a perfect tool for me to express how I felt about male relationships. And sort

of distance myself—by not actually painting a real person."

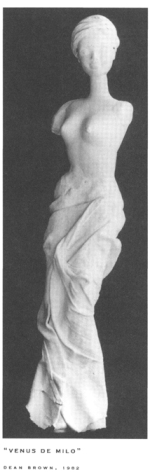

Photographer Dean Brown also makes a personal statement with Barbie, but it is about art history. He began using her as a

model in 1980, while he was stationed with the United States Information Agency in Pakistan. Americans were not popular there

at the time, and Barbie was less likely to smash his camera in a rage than were the people he photographed on the street.

The result of his efforts was

A Capricious History of Western Art,

a portfolio that begins with a pastiche of the Lascaux cave paintings and ends with a variation on Marcel Duchamp's

Nude Descending a Staircase.

Brown also includes a gallery scene in which contemporary Barbies and Kens gaze at miniatures of his pictures.

In addition to Brown's wit, the first thing that strikes the viewer is how far the 1950s ideal of female beauty, which Barbie

embodies, deviates from the classical ideal—not to mention from Vitruvian mathematical standards of human proportion. No way

is that doll's foot one-sixth of her height; at just under an inch, it is closer to one-twelfth. The second is the extent

to which Barbie is a natural model for works that derive their erotic energy from the display of breasts: Delacroix's

Liberty Leading the People,

Manet's

Olympia,

and the

Venus de Milo.

Painted by Eugene Delacroix, whom Anne Hollander termed "the greatest Romantic expositor of complex passion through mammary

exposure," the original Liberty's fascination owes much to "her gloriously lighted bare breasts." Brown's Liberty does not

thrust her flag forward as Liberty does in the Delacroix version. She demurely picks her way over a sprawled G.I. Joe. She

is above the battle, not within it; the vacuity of her expression precludes passionate engagement. She is a distant Liberty

for a distant video-game war—and, significantly, the photograph is now in the collection of a female reporter to whom some

Iraqi soldiers had surrendered during the ultimate video skirmish, the Persian Gulf War.

The

Venus de Milo

is another sculpture in which breasts are strongly eroticized, though Brown's version is more unnerving than voluptuous.

Barbie is way too skinny to pass muster as a Greek goddess; she looks as if she has been placed on a rack and stretched. Nor

does Barbie's legginess work for her. Draped female legs, like those of the original Venus, were considered beautiful in classical

art; exposed ones, by contrast, connoted not beauty but strength, and were found on depictions of Artemis, a hunter and warrior.

Brown worked hard to transform Barbie into Venus; he chopped off her hair, wrenched off her arms, and bundled her legs in

"a man's big white handkerchief" slathered with Elmer's glue. From clay he fashioned arm shards, nipples, and a navel; then

he covered his handiwork with white paint. None of these affectations, however, diminished the perkiness of her expression

or, for that matter, of her breasts.

In terms of body type, Barbie was far more suited as a stand-in for Manet's

Olympia.

Manet had painted a contemporary courtesan; in Brown's version, Barbie has never looked tartier—every bit a descendant of

the sleazy

Bild

Lilli. By shrewdly posing his Olympia with crossed legs, Manet managed to avoid the issue of depicting pubic hair, eliminating

what would have been a dramatic contrast between a human model and Barbie. And of course because Brown has used a current

edition of the doll, his Olympia fixes the observer with the dead-on stare that so flustered viewers of Manet's original.

Now retired and living in suburban Maryland, Brown is currently working on "the original women's lib thing," Judith with the

head of Holofernes, for which he bought a detached Ken head at a Barbie convention in 1987. Far from wishing to extirpate

her eleven-and-a-half-inch rival, Brown's wife is trying to dissuade Brown from his latest venture: Barbie's funeral. "I've

got a casket all made, and my wife doesn't want me to do it," he complained. "She doesn't like the idea of Barbie dying."

But having given Barbie a navel—and, by implication, mortality—Brown has made the macabre scene logically inevitable.

(Photographer Felicia Rosshandler, by contrast, has had no inhibitions about killing Barbie and her kind; her chilling

Twilight of the Gods

features a close-up of an arched fashion-doll foot, tagged as if it were on a slab in a morgue. "To me, Barbie dies when she

puts on her wedding dress," Rosshandler said. "She never ages; she never becomes a mother.")

Charles Bell's mural

The Judgement of Paris

also deals with death—and love. The famous scene, rendered by dozens of painters, depicts the first beauty contest, in which

Paris, portrayed by a Ken doll, is forced to choose between Minerva, portrayed by a Barbie doll; Juno, portrayed by a Miss

America doll; and Venus, portrayed by a Marilyn Monroe doll. Paris, of course, selects Venus—that is to say, love—and his

choice leads to a megadisaster, the Trojan War.

The painting is different from Bell's other work—huge, photorealistic canvases of metal toys and pinball machines. And it

is bittersweet; the myth he dramatizes is about opting for passion, even when it is fatal. "In the era of AIDS, I'm overwhelmed

by the temporariness of life," Bell told me. "In the context of discovering our own mortality, things that had seemed important

become less important. Eventually human kindness—and love—are the only things that really endure."

If Mattel has its way, however, corporate control of its icon will endure. A mere note from the toy company squelched

The Barbie Project,

an unauthorized theater piece that dramatized Mattel's corporate history and how children play with the doll, which was produced

in 1980 at the Theater for the New City on Manhattan's Lower East Side. The show's director, Lauren Versel, who had initially

petitioned Mattel for permission to film a documentary, didn't think her vision would ever be compatible with the company's.

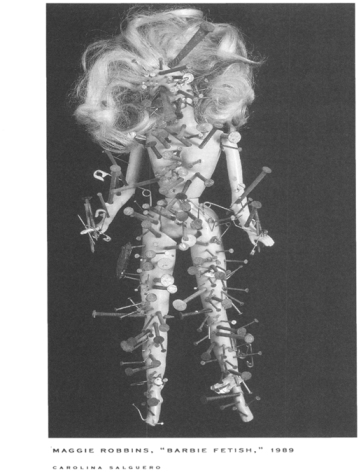

Mattel has frozen other projects—Robin Swicord's musical comes to mind—but with visual art, its current tack seems to involve

sponsoring authorized shows. In 1994, Mattel Germany opened a display of corporate-approved Barbie art in Berlin. Exhibited

at the Werkbund-Archiv in the Martin-Gropius Bau (a gallery with a history of interest in commercial design), the pieces tended

to be flashy but empty. Most involved clothing Barbie in exotic outfits. Yet there were a handful of images that made one

look twice, and that might have raised Jesse Helms's blood pressure. These included depictions of lesbianism (after commenting

in the exhibition catalogue that Barbie, at thirty-five, was "at last grown-up," artist Elke Martensen showed her in a leather

helmet caressing the bare breast of another Barbie), fetishism (artist Holger Scheibe constructed an image of a sweaty, bare-shouldered

adult male directing his puckered lips toward a Barbie clutched in his fist), and bestiality (artist Peter Engelhart placed

Barbie in a "lovematch" with King Kong). And for crude sexual puns and sick-making imagery, Frank Lindow's

Barbie, ich hah dich zum Fressen

gem! (Barbie, I would like to eat you!)

stood out: It featured blond Barbie and Asian brunette Kira "pickled" like fetuses in mason jars. But with these exceptions,

the overall effect was bland.

American photographer David Levinthal was not included in the German show, but he is among the artists participating in Mattel's

upcoming official coffee-table book—and the difference between the images he produced for that project and the ones he did

for himself says much about the problems of working with corporate-controlled icons.

Levinthal is perhaps best known for

Hitler Moves East,

a book collaboration with Garry Trudeau that he began while at Yale Art School, from which he received an M.F.A. in 1972.

In it, he photographs toy soldiers so that they look like real ones, ominously charting the course of the Second World War.

His subsequent work has also pushed boundaries. In 1991, he executed a series called

Desire,

made up of enlarged Polaroids of miniature Japanese dolls that depicted Caucasian women in bondage. In soft focus, their surface

was beguiling and seductive, but their content was disturbing— particularly to women. "I wanted people to look at these images,

which I thought were very beautiful, and sort of halfway think, 'Wait a minute, I'm looking at an image of a woman tied in

a chair, there's something wrong.'''

In graduate school, Levinthal began investigating sensitive sexual themes with Barbie and G.I. Joe. "I did a sort of narrative

where Barbie had this straight preppie boyfriend. But she's attracted to this rough Vietnam vet," he explained. "The 'seventy-two

ones just hit you because it's right there. . . . The race thing was very much in evidence in the late sixties, early seventies—

the idea of Barbie as the Aryan virgin, and this character breaking through that. I called him G.I. Jose—that was at the height

of my political incorrectness."

Yet his work for the authorized project, while it has an abstract beauty, lacks bite. "There was in the contract that there

would be some editorial review, and I think anyone could use their own good sense and realize that you would try and make

the work more accessible and less confrontational," he told me. "I wasn't going with the idea of saying, 'Let's really challenge

with what we've got here.' " And he didn't.

F

iona Auld credits Elizabeth Taylor with introducing her to Barbie. In 1990, after correctly identifying Taylor's favorite

color (purple), her first film

(There s One Born Every Minute),

her most famous jewel (the Krupp diamond, given to her by Richard Burton), Auld, from Paisley, Scotland, won first prize in

a contest sponsored by Taylor's Passion Perfume.

Soon she and her husband, a computer programmer, were on an all-expenses-paid trip to Las Vegas, San Diego, Los Angeles, and

Hollywood. "I stayed at the Beverly Hilton; I had champagne; I had caviar; I was driven around in a limousine," she told me.

But it was in Anaheim, California, that Auld's life changed. She visited a doll museum and became an almost instant convert

to Barbie-collecting.

Auld began to amass dozens of dolls, virtually turning over her dining room to Mattel. Her five-year-old daughter was warned

to steer clear of the treasures: "She has her own Barbies; she knows that she can look at but not touch mine." And when Auld

placed an ad in

Barbie Bazaar,

requesting "BARBIE LOVING PENPALS FROM THE U.S.A.," there was no turning back. Thirty-five people responded, six of whom she

met for the first time at the 1992 Barbie-doll collector's convention in Niagara Falls.

Auld did not conceal her heritage at the conference. Sporting a tartan and a tam-o'-shanter with a red pom-pom, she appeared

in the life-size doll-clothing fashion show as Barbie in Scotland. Like the Native American Barbie, which doesn't replicate

the costume of a particular tribe, Mattel's Scottish Barbie doesn't wear the tartan of a specific clan. Auld, however, personalized

her costume by wearing the pattern of her own—MacLennen—clan.

Nor was Fiona the only non-American-born collector on the runway. Ex-beauty queen Corazon Ugalde Yellen, daughter of a Philippines

air force general under Ferdinand Marcos, executed a few theatrical turns as Barbie in the Philippines. Unlike the other participants,

for whom the show appeared to be a goof, Yellen strutted crisply and imperiously—hips tucked forward, shoulders thrust back—as

if she were vamping down a Paris runway. Before moving to Beverly Hills, she was a professional model, having posed for Macy's

and Western Airlines.

Next came Rebecca Taylor, a wispy young woman from Tyler, Texas, dressed as Casey, the Mod waif with a single earring whom

Barbie befriended in 1968. With one ear tinted kelly green, Taylor elicited first a groan, then applause from the crowd. The

earrings on most vintage dolls stain their lobes with an unsightly emerald-colored eczema that, because it cannot easily be

scrubbed off, is the bane of many a collector's existence. Taylor was followed by Judy Roberts of Spokane, Washington, who

persuaded her husband Gary to model "Business Appointment," an outfit from the days when Ken still shopped at Brooks Brothers.

No two collectors are identical. Some women started amassing the dolls when they were children; some women began when they

had

children; and others aren't women at all—roughly a third of the delegates in Niagara were men.

Nor can one generalize by disposition or demographics. Some are misers, who puff up when describing the financial worth of

their collections; some are innocents, who do not see the dolls as constructs of class or gender but as awe-inspiring miniatures;

and some are sophisticates, who see the doll and her paraphernalia as campy artifacts of middle-class life—or "life," since

camp sensibility requires a certain sardonic detachment. There are celebrity collectors like Danielle Steele, Roseanne Arnold,

Demi Moore, and Norris Church. Many, however, seem to be like Auld—for whom Barbie is not an end in herself, but a pretext

for making friends around the globe.

At the 1992 convention, I felt as if I were on a theme-park ride. I ate lunch the first day at a table hosted by an African-American

collector, who lured me to her room for a peek at a prized possession—an issue of

Hustler

from July 1976 that featured a photo spread entitled "Vulva of the Dolls." I do not recall the images clearly, but in my notebook

I jotted: "Bugs Bunny violates Francie with plastic carrot." Also at my table were Bob Young and Richard Nathans from Tempe,

Arizona. Long before Mattel issued

Dance!

Workout with Barbie,

Young had been animating the doll, frame by frame, manipulating Barbie in an aerobics routine with his grammar-school-age

niece.

The convention food seemed straight out of childhood: red Jell-0 with fruit and, at the Saturday night banquet, pineapple-glazed

ham. Mattel's presentations also had a grade-school quality, like filmstrips for social studies class. The most surreal was

a slide show, narrated by designer Carol Spencer, that traced the evolution of her Classique Collection from its inception

(she designed the outfits while watching

Murder She Wrote)

to its production in Mattel's two plants in China. "The bicycle is the most common transportation means in China," Spencer

recited as slides of Chinese peasants and bicycle racks appeared on the screen. "It's my understanding that they're not allowed

to own automobiles." Next came shots inside the factory: Asians peering at tiny objects in front of large machines. "This

is the heat setting of the rhinestones on the tights of Hollywood Premiere Fashion," Spencer said. "They're placing the rhinestones

with tweezers onto a special fixture, and positioning the fabric over the rhinestones, and then the press goes down and heat

actually sets the rhinestones onto the garments."

Other processes included face-painting and eyelash-rooting ("an extremely difficult operation . . . the operator was trained

for two months"). The crowd applauded wildly when Spencer's Benefit Ball Barbie—the Georgette Mosbacher look-alike—had her

eyelashes installed and clipped.

The convention had one redemptive moment. Doll authority Sarah Sink Eames had been rumored to have information about a prototype

for "Colored Skipper"—Barbie's African-American sister, who antedated Black Barbie by several years. Eames not only confirmed

that such an object existed, but that it was in her collection.

Many collectors told me that the 1993 convention in Baltimore, hosted by doll artist, illustrator, and former window-dresser

Mark Ouellette, was a splashier production than the one in Niagara. It had six hundred participants and a waiting list of

three thousand. But such extravaganzas are a recent phenomenon. The first Barbie conclave, held in October 1980, attracted

under two hundred people. It took place in Queens, New York, at the Travelodge International Hotel, not far from Kennedy Airport.

Sybil de Wein, who, with Joan Ashabraner, published

The Collector's

Encyclopedia of Barbie Dolls and Collectibles

in 1977, was another key figure in the first wave of collectors. Referred to by Cronk as "our Barbie Dean," De Wein floated

through the 1992 convention like a sort of dowager empress. Even with a broken elbow, the doughty widow from Clarksville,

Tennessee, managed to comport herself with the dignity one expects from a Southern Lady. She graciously signed copies of her

book when new collectors came to pay court.

Although doll aficionados had probably been stockpiling Barbies since 1959, they didn't get organized until the seventies.

Back then, camaraderie took precedence over commerce. Collector Ann Nawricki "got us started on the right foot by reminding

us that no matter how we love dolls they are still inanimate objects and are never as important as people (and friendship),"

Cronk, editor of the Barbie collectors' bimonthly newsletter, wrote to its six hundred subscribers in September 1979.

By January 1980, Cronk's bulletin,

The Noname Newsletter,

had a fancy new title—

The International Barbie Doll Collectors Gazette

—and a stylish logo with drawings by artist/collector Candy Barr. Cronk, however, maintained an unprepossessing tone, often

telling stories in an Erma Bombeck voice about her own Barbie-related mishaps. At one point, a network TV crew asked her to

demonstrate her dolls, including the 1979 Kissing Barbie. "They had me holding her at a very difficult angle," Cronk wrote,

"and in the process of struggling to hold her still and press the plate, I pulled her bodice down, leaving her topless on

CBS's film." Then there was the time she tried to conserve money for Barbieana by making her children purchase the family's

shampoo. "Before leaving for Girl Scout camp, I found myself shampooing with something called strawberry Earth Born Shampoo,"

she writes. "The following day I was pursued by about 1,000 bees, all trying to pollinate me! The next time Scott's turn rolls

around to buy shampoo I just pray it doesn't turn out to be Banana or I will make sure I avoid the zoo!"

Cronk also offered her opinions on new products. "The thing that really rings my chimes," she wrote in February 1980, "is

the new commode. . . . We can truthfully say Barbie has everything now as her pink commode has real 'flushing' action! It

is pink and there is no mistaking who it belongs to as her name is on the tank! Part of the dream furniture grouping, it comes

with a small chest with towels (what, no toilet paper?). Another new item is a round bathtub with continental shower. . .

. Where does the water go? Hmm, come to think of it, where does the water go in the toilet?"

But for Cronk, the highlight of 1980 was meeting Charlotte Johnson at Barbie's twenty-first birthday party during Toy Fair

on February 11. Johnson, who had just retired, regaled

Gazette

editors with war stories, including the trials of designing a Barbie-sized mink coat for Sears. The

Gazette

ran her photo in front of a revolving display of historical Barbies. It was among her last public appearances; felled by Alzheimer's

disease, Johnson is currently in a nursing home.

Collecting has changed a lot in the fourteen years since that first convention, however. "There used to be a preponderance

of older women whose children had Barbie and they wanted it," said doll dealer Joe Blitman. "Now it's different. There's a

new guard of people in their late twenties to early forties—probably two to one, female to male. And it's a more urban group."

Whether they amass Barbies or bric-a-brac, Kens or incunabula, Francies or Faberg6 eggs, collectors frequently share certain

personality traits— acquisitiveness, obsession, and an intense connection to objects, sometimes at the expense of people.

In

Collecting: An Unruly Passion,

psychoanalyst Werner Muensterberger locates the beginning of the collecting impulse in early childhood—"in the objects that

are always there when the child's need for comfort... is not immediately met; when the child does not have a mother's breast,

or a loving pair of arms to allay frustration." For many grown-up collectors, to pile up treasures is to stave off childhood

feelings of abandonment, to erect a tangible (yet frangible) hedge against ancient anxiety. The urge begins with a child's

first "not-me" objects—Winnicott's transitional objects—a category into which, as we have seen earlier, Barbie sometimes falls.

But even when objects are not intended as playthings they often function that way within their collector's psyche. "What else

are collectibles but toys grown-ups take seriously?" Muensterberger asks.

Sometimes the lust to amass new and snazzier objects can dominate a collector's life, just as betting dominates the life of

a gambler. It can even supersede work and family, Muensterberger says. "It's an addiction," explained Jan Fennick of J'aime

Collectibles, an antique-doll dealership on Long Island. "There are a lot of layaways. They'd sooner buy Barbie clothes than

buy clothes for themselves. They see something they want at the prices they want, they figure they won't be able to find it

again. The shoes can wait; or the house can wait; or the car can wait. . . . Nobody's starving or homeless because of Barbie,

but people joke about it."