Forever Barbie (28 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

The Mom doll's face, modified by Haynes, is almost as scary as the Mom doll's behavior. Mom makes Karen wear hip-huggers that

Karen believes make her look fat. Mom won't let Karen or her brother Richard move out."No matter how famous you all get,"

Mom says ominously, "you're going to keep living at

home."

Home is Downey, California—a grid of houses that resemble the Barbie doll's fold-up dwellings. As poignantly tacky as Karen's

songs, Downey's matchbox mansions are an emblem of the postwar prosperity that changed the relationship of middle-class consumers

to their food. After Haynes's camera has panned down a suburban block, it sweeps down a supermarket aisle—visually equating

prefab houses with packaged foods—while a voiceover explains how, after World War II, food became more convenient, varied,

and plentiful. But in defiance of this bounty, teenage girls began, in increasing numbers, to starve themselves.

Haynes makes an ironic connection between anorexia's symptoms and the content of the Carpenters' lyrics. After explaining

the "high" that some anorexics get from constant hunger, Haynes cuts to the voice of Karen singing, "I'm on the top of the

world looking down on creation . . . " And during Karen's short-lived marriage, the soundtrack plays "Lost in the Masquerade."

Yet even when Haynes uses the Carpenters for social commentary—they crooned their escapist lyrics at the White House the year

Richard Nixon ordered the Christmas bombing of Cambodia—he never lets the political overwhelm the personal.

Superstar

contains many frightening images: shots of bombs falling and a red, white, and blue Ex-Lax box that flashes across the screen

like a malignant American flag. But by far the scariest shot is filmed from the Karen doll's point of view. It shows her family

hovering over her as she wakes up after fainting from malnutrition. "You're going to be under Mom's constant care," the Richard

doll says, his face whittled into a malevolent grimace. "She's going to fatten you up."

Like puppets in a performance piece,

Superstars

dolls are never intended to be seen as anything other than dolls. The film is innocent of slick special effects. "This work

is part of a tradition of independent, antimainstream, anticommercial filmmaking," explained John G. Hanhardt, curator of

film and video at the Whitney Museum of American Art. "It's made by an individual with a limited budget. And rather than that

becoming a problem, it's the aesthetic of the piece.

"These dolls are sold as representing a way of looking, a way of appearing, a way of dressing, and a way of living," Hanhardt

continued. And what Haynes does is rupture the seamlessness of that appearance. "He shows the complexity of the Carpenters

as people," Hanhardt said, "and how they had to remake themselves into these popular icons—these things to sell."

Psychotherapist Laura Kogel remembers that the movie gave her chills. "They had to do with Karen not being seen as a person,"

she said. "And consequently she didn't see herself that way. You come to see yourself as a person through the eyes of those

who raise you."

But the endorsement of critics and therapists was not enough to keep

Superstar

in circulation. "When the film came out, we had many rentals to clinics and classes that dealt with eating disorders," said

Christine Vachon, a producer at Apparatus, the film company Haynes founded. "Everybody felt the subject was treated respectfully.

It moved many people to tears." Because Haynes hoped the Carpenter family would allow clinics to show the film, he offered

to donate all its profits to the Karen Carpenter memorial fund for anorexia research. "And they said no," Haynes said. "That

really disappointed me."

IF PROFESSIONAL MODELS WERE FORCE-FED

SUPERSTAR,

fashion magazines might look very different. In a 1993

People

cover story, top models Kim Alexis, Beverly Johnson, and Carol Alt discussed the prevalence of eating disorders among models

and how they had starved themselves to stay thin. Not to be outdone by her sister, Christine Alt, now a five-foot-ten-and-a-half-inch,

155-pound, "large-size" model, revealed that she had pared herself down to 110 pounds and developed an ulcer. "When Karen

Carpenter died of anorexia," Christine said, "I remember seeing her picture in

People

and thinking, 'God, how lucky she was because she died thin.'"

JAUNE QUICK-TO-SEE SMITH, "PAPER DOLLS FOR A POST-COLUMBIAN WORLD WITH ENSEMBLES CONTRIBUTED BY U.S. GOVERNMENT," 1991

COURTESY STEINBAUM KRAUSS GALLERY, prevalence of eating disorders among

M.Y.C.

Christine's remarks make one wonder about the Alt family. Sibling rivalry takes many forms, but sisters don't usually compete

to see who can lose the most weight without dying. As near as I could tell, the problem with these models was that they only

saw themselves as objects. True, by defin-ition, a model commodifies her body, but that commodification doesn't have to erase

the person inside.

Still gorgeous at fifty, Lauren Hutton is proof that models can retain a sense of themselves as subjects—which, for older

models, may make the difference between working or fading away. In an industry where "live dolls" used to be discarded when

they showed signs of age, Hutton has made the transition from beautiful "girl" to beautiful "woman." She seems more visible

as a model now than she was twenty-five years ago.

"When I first started modeling, I mostly worked for bad stylists in bad catalogue houses trying to get a break," Hutton told

me. "And it was amazing. People would treat you like this sort of anonymous doll. They would touch you and be talking to each

other—and I wasn't used to people touching me. I have dimples in my earlobes and I had a stylist try to smack a pair of pierced

earrings through my dimples. She had her head turned talking. And I just went straight into the air because there were no

holes there.

"The reason you become a successful model is because you learn how to make people see you as a person," she continued. "Not

anonymous. You find a way of making contact. Of course, once I became famous, people were terrified of touching me in any

way. But that's a whole other category."

Throughout her career, Hutton has defied the doll-like uniformity traditionally associated with models. On the advice of

Vogue

arbitrix Diana Vreeland, she refused to "correct" the now legendary gap between her front teeth. And in 1988, when she became

the centerpiece of a Barneys New York ad campaign, she shattered the rule that live dolls don't age. "I thought it would be

cool to show that someone who had been around awhile could be atrractive," Glenn O'Brien, creative director of Barneys, told

me. "In a way, Hutton looks better now. Her character has kind of jelled. She isn't just a mannequin."

Significantly, Hutton has refused offers from toy companies to make a doll in her image. The first request came at the beginning

of her career; the second in the late eighties, about the time Matchbox Toys issued its "Real Model Collection" with likenesses

of Christie Brinkley, Cheryl Tiegs, and Beverly ("I ate nothing. I mean nothing") Johnson. "I had this instant repulsion at

the idea," Hutton said. "And it was a weird feeling because I was flattered and repulsed at the same time."

In part, this had to do with her childhood distaste for baby dolls. "They looked larval," she told me. "What I really liked

to do was to take their heads off and try to figure out how their eyes opened and shut. I never found out, because once you

have the head off, you can't ever get the eyeballs back in. But with each doll, I convinced myself that this time, I would

find out their secrets. So I decapitated many."

After some reflection, however, she discerned what really bothered her. "Giving little girls anything that makes them want

to emulate a totem or an individual—rather than a generic idea of girlhood or womanhood—seems to be very unhealthy," she said.

"It's like bad karma. If the greatest destiny is to find your own unique path, then one of the worst things you can do is

suggest that people follow your way. I am not a totem. I have three younger sisters that I helped to raise, and when I started

modeling, I wouldn't let my mother put my pictures up anywhere in the house."

Hutton was sixteen when Mattel brought out Barbie, a doll that didn't exactly win her heart. "I thought it was even creepier

than the larvae I had beheaded," she said. "But when Brigitte Bardot came out, I remember thinking that she and the doll were

sort of similar. You could say the first great international icon was Bardot. She was always pictured in a bouffant gingham

skirt—spaghetti straps, big bouffant, and a tiny, tiny waist. She had that long fine neck and these long, long bones. And

she'd be up on real high heels. And we were all trying to look like that."

Except that unlike most of her peers, Hutton was successful at it—which galled other women. "I would have women be incredibly

rude to me right to my face. Rude and feline and mean—when I was as innocent as a lamb, just standing there. I've always liked

women, so when they were rude, I would assume I'd misheard them." But as Hutton's celebrity grew, she had to acknowledge that

her ears worked fine: "You'd go to dinner and the wife would shake your hand and her opening words would not be, 'Hello, how

are you?' They would be, 'Oh, I hate you. When my husband said you were going to dinner, I said, Oh, my God, not

her.

Yet when Hutton herself matured, she understood the resentment. "It took me about seven years to turn forty," she said. "I

went from thirty-eight to forty-five and it was so horrible and so painful. I had been a celebrated 'girl,' and suddenly I

was a woman and there was no place for women in our society— unless they had made some incredible mark, usually by imitating

a man, in a business way. When I was turning forty, sometimes I would see a beautiful young girl and I would get so confused

I'd want to hide. I suddenly understood what a lot of the feelings toward me had been about. And I had real sympathy. I would

feel jealousy deep inside—and I would be very ashamed of myself because I've always loathed that in me, at any time about

anything. I was seeing someone young and beautiful and I didn't feel that I was young and beautiful. And in fact, I wasn't:

I was no longer a girl."

"But you were still beautiful," I couldn't help blurting.

"The beauty of women was not accepted or celebrated," Hutton explained. "It had no credentials, was not certified, was not

allowed, did not exist in our society. It's a brand-new idea and it's just happening now in America."

If Hutton is right, this could mean a new challenge for Mattel: Mature Barbie. Not Crone Barbie or Decrepit Barbie, but a

Barbie who's been around the block, and looks better for the wear.

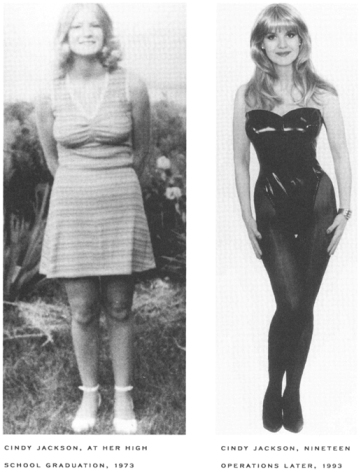

C

indy Jackson, the Fremont, Ohio-born founder of the London-based Cosmetic Surgery Network, may be the ultimate Barbie performance

artist. She has had more than twenty operations and spent $55,000 to turn herself into a living doll. She has had chemical

peels, tummy tucks, facelifts, eye-lifts, breast implants, and liposuction. She has even had two nose jobs.

"I'm registered with the British Internal Revenue as the Bionic Woman," she explained. "I run my cosmetic surgery bureau as

a firsthand experience, so all my operations are tax-deductible. . . . The BBC even paid for my boob job." But no longer is

she satisfied merely remaking herself. Her mission, which evolved while assisting other women through Barbie-izations, is

to create "a bionic army."

In Barbie's early years, Mattel struggled to make its doll look like a real-life movie star. Today, however, real-life celebrities—as

well as common folk—are emulating her. The postsurgical Dolly Parton looks like the post-surgical Ivana Trump looks like the

postsurgical Michael Jackson looks like the postsurgical Joan Rivers looks like . . . Barbie. This chapter will not deal with

body image, ethnic identification, or self-esteem. It is about nuts and bolts—Mary Shelley—scalpels, silicone, and sutures.

Cindy has earned a section of her own.

When we met at Sfuzzi, a restaurant on Manhattan's Upper West Side, for dinner in 1993, Cindy's lower lip was the only part

of her body that had not been modified—and she had spent the afternoon talking to a Park Avenue doctor about enlarging it.

She also wanted a fat transplant in her cheeks. "I have dents here which need filling in," she explained. "See my cheek here

is flat—but I have dents underneath."

"I can't see them," I said.

"But they're there," she assured, craning forward so I could get a better view. Then she scrutinized me. "You don't need your

eyes done," she said. I had discussed my drooping lids—and fear of pain—in a phone conversation months earlier. "Everybody's

eyes will sag after a certain point." My jawline, however, was another story. "You might do a little liposuction there. But

I wouldn't say it's an emergency case. Work on keeping your chin up a little."

As I involuntarily thrust my jaw upward, Cindy pulled out a hefty album of her "before," "after," and "during" photos. "This

is what you look like when your eyes need doing," she explained, pointing to a snapshot of herself at twenty-seven, about

ten years ago. She did indeed have slits for eyes and a posture reminiscent of Ruth Buzzi's character on

Laugh-In.

Blond, slender, and almost nondescript in her "prettiness," Cindy today is not Barbie's twin, but she does look more like

the doll than she did when she started. She also favors Mattel fantasy clothes: glittery earrings, sleek, short skirts. We

ordered dinner—a vegetarian pizza. Like the 1989 Animal Lovin' Barbie, Cindy is an ardent antivivisectionist. She has "adopted"

a whale, belongs to "Cheetah Watch," and doesn't eat meat.

As we studied a picture of her post-op face, bruised and looking troublingly like the eggplant appetizer on an adjacent table,

she told me, "I want patients to understand that it's major surgery. It's not like going to the beauty shop. There are real

dangers—complications that happen, rarely, but they do happen."

Then she moved on to her philosophy. "Men are really drawn to women for their looks," she said. "They can't stand a sick woman,

much less a sick, ugly, swollen woman. Besides, I think men worry that you're going to die on the operating table and there'll

be nobody there to make their dinner."

As if on cue, our dinner arrived. Avoiding animal products is the extent of Cindy's health regimen; she keeps "fit" through

surgery. "It's not me to go to a gym and exercise . . . I don't know that it's really good for you. You go to the gym and

you have to keep going. I'm careful who I sweat with, too. I don't like to go in those places and do all those things. Especially

now— people expect me to be perfect." She told me about her plans to have the loose flesh removed from her upper arms, an

operation in which the scarring itself causes the muscles to appear taut. Thinking of the hours I had logged on the Gravitron

to vanquish my own vexatious jiggle, the operation seemed almost a good idea. Then my eyes returned to Cindy's "in-between"

photo. Cowardice, I concluded, was the better part of valor.

Cindy believes her appearance in the

National Enquirer

in January 1993 may have been responsible for Roseanne Arnold's decision to have a total surgical overhaul: that, in a sense,

she recruited Arnold into her "bionic army." "ROSEANNE'S HUBBY IN PLOT TO ROB BANK: TOM ARNOLD'S OWN AMAZING CONFESSION" appeared

on the newspaper's front page, along with "AMY FISHER: I SHOULD HAVE SHOT MY LOVER" and "WYNONNA JUDD FIGHTS BACK: I'M NO

LESBIAN." Cindy and her transformation were prominently featured—hard for Arnold, had she seen the issue, to have missed.

And Arnold these days is certainly a fascinating surgical confection: a zaftig woman with the cheekbones of Audrey Hepburn.

Having once been applauded by feminists for her defiant refusal to look like a model, Arnold is now defensive about her makeover.

"Well, we're not in a perfect feminist world," she told Liz Logan in

The Ladies' Home Journal.

"And we never will be. And even if we were, I would still have plastic surgery. It makes you feel really good about yourself.

I mean, you have flaws that bother you and to erase them is great." A paraphrase, it struck me, of Cindy's surgery-is-power

philosophy.

Before I met Cindy, I watched her on

Maury Povich,

stoically enduring the taunts of audience members who suggested that her money might have been better spent on psychotherapy.

She was quick with snappy rejoinders— a skill essential for tabloid television.

"Jenny Jones

was my worst experience," she recalled. "They put me on with Queer Donna, who's a 360-pound gay man who parodies Madonna and

worships her. Also with Frank Marino, a guy who had surgery to look like Joan Rivers, and a Cher look-alike who was also a

man." Then a "plant" in the audience commented, "Everybody knows Barbie doesn't wear any underwear. Are you wearing underwear?"

"Yes," Cindy snarled, "are you?"

She scowled. "I didn't grow up to be Barbie to be victimized like that. When I do the shows, I get to go home—I get a free

trip, that's why I do it." "Home" now for Cindy is outside Chicago, where her sister lives. She is deliberately vague about

the location because her sister, a married executive, frowns on her surgical way of life; she won't even have her ears pierced.

"She has the perfect life and I have the perfect face and body," Cindy said.

Cindy does not have fond memories of her childhood in Fremont, where, as a teenager, she worked in a ketchup factory. There

was the indignity of catalogue-shopping—tracing the outline of her feet to order shoes that pinched, like the pennies that

were expended to buy them. But even amid the meanness, hope effervesced: in the form of a stylish doll with a bubble cut and

curvilinear shoes that hugged its curvilinear insteps. Barbie didn't have a husband or babies; Barbie had careers . . . and

options.

"I watched my mother give her life to be overrun by a man—my father," Cindy told me. "And not to fulfill her potential because

of men and children. If I didn't have that freedom, I wouldn't have that husband or partner." Cindy's boyfriend, an audio

engineer she met while performing in a rock band, is, she told me, very Ken-like—and to her, male good looks are as important

as female ones. Like Barbie, however, she seems to prefer freedom to marriage.

Even though they have no financial relationship—Cindy considers surgery consultants in the pay of physicians to be unethical—one

compatriot on her surgical crusade is Dr. Edward Latimer-Sayer, an English plastic surgeon. "Although Cindy has always talked

about this Barbie-doll image, in England at any rate, the Barbie doll is associated with stupidity— a sort of nice body, vacant

brain sort of thing," Latimer-Sayer told me. "And Cindy is anything but that." Although she dropped out of art school before

moving to London to work as a photographer, she is well spoken and well read. She is also a member of Mensa.

Latimer-Sayer urged Jackson to get greater firsthand knowledge of surgical procedures. "He kept inviting me to operations

and I finally went," she said. "I can see I'm going to be a regular fixture in the operating room."

Most of Latimer-Sayer's patients are not like Cindy—who, because of her consumer watchdog organization, gets celebrity treatment.

"I think I'd starve to death waiting for the models and actresses to show up," he told me. "The majority of my patients are

housewives, nurses, hairdressers, secretaries. Ordinary people. They don't want to be out of the ordinary, but they just feel

that one particular part lets them down. An attractive young girl with a big hooky nose doesn't feel normal."

Significantly, Latimer-Sayer's patients don't choose their doctor; he chooses them. A satisfied patient, he believes, is one

with realistic expectations. When, for instance, I told him about my fear of pain, he suggested I might be a poor candidate

for surgery. Some procedures require greater screening than others. "Liposuction is an operation where you really have to

choose your patients well," he said. "You get a bulky patient and you try and get the fat off them, it simply doesn't work.

You end up with lumpy, irregular areas and the skin hanging in folds.

"I identify with the patient what the aims of each particular operation are," he told me. "I mean, I don't mind patients having

lots of operations. After all, I've got children to send through university." Latimer-Sayer also believes in using his time

efficiently—especially with things like breast implants. "Some people fiddle about for hours—one wonders what they're doing.

. . . But once you've done a few hundred, you ought to know where to cut the pocket and what size fits the pocket. In the

main, operations take less time this side of the Atlantic than they do in America. Because American surgeons are looking over

their shoulder for the lawyers all the time."

In talking with Latimer-Sayer, I got the sense that the hows of surgery were more important than the whys. Decisions to, say,

westernize Asian eyelids should rest with the patient, not the surgeon. "If you have the double fold—what they call the European

eyelid—you are considered more trustworthy, higher class, and you're more likely to do well in life," he told me. "If you

have the Oriental eyelid with the thick upper lid with no fold, it's like being a second-class citizen. . . . Now if there's

a little simple cosmetic operation to make somebody go from a second-class citizen on appearance to a first-class citizen

on appearance, no wonder it's popular.

"If for instance, someone had developed a technique to make black people white . . . they would have been swamped, wouldn't

they? Not because there's anything wrong with being black, but it's nicer to be white in a white society."

There is, however, one process he wouldn't touch with a ten-foot pole: penis enlargement. "A lot of men seem to want it,"

he said. "You take a bit of fat from somewhere where there's a bit to spare and put it in the penis and it's fatter. But the

trouble is that fat doesn't stay there; it tends to absorb, and sometimes you can get all sorts of other troubles with it.

It can generally turn into a horrible mess."

Cindy concurred: "As far as I'm concerned, with men who aren't very well endowed, it's cheaper to buy a Porsche and probably

more safe."

Latimer-Sayer did not install Cindy's breast implants; they were put in as part of a BBC documentary on the process. And they

have begun to cause trouble. They were supposed to have been placed behind the chest muscle, but one migrated; it has also

hardened, a process known as capsular con-tracture. "I'm not happy with the encapsulation of my own implants," she told me.

"I'm having them out." And yet, she said, pausing, "it's better to have had them and liked them than never to have had them

at all."

In her role as watchdog, Cindy is also following the class-action suits filed by unhappy implant owners against Dow Corning,

a maker of silicone implants. In April 1994, about a year after she and I had dinner,

The New

York Times

reported that the lawyers representing the patients had unearthed a 1975 study by company researchers that showed that the

silicone in the implants harmed the immune system in mice. Whether this fresh detail will slow recruitment for her bionic

army remains to be seen.

One thing, however, is certain: there are already a lot of bionic women out there. "I don't even think I want to walk down

the street in California," Cindy told me. "They've all done what I've done. Over there I'm just another Barbie doll."