Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 (3 page)

Read Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 Online

Authors: Rana Mitter

Memories of the war against Japan can also heal scars left by another conflict, the painful civil war between Mao’s Communists and Chiang’s Nationalists. One of the most startling sights for anyone who remembers Mao-era China is the villa at Huangshan that once belonged to the chairman’s old foe Chiang Kai-shek. Today the villa is restored to look as it did during the war years, when Chiang lived there, writing of the Chongqing bombings in his diary. The displays inside give plenty of details of Chiang’s role as a leader of the resistance against Japan, all of them very positive, and none painting him as a bourgeois reactionary lackey. Of the Communists, there is very little mention. A generation ago, one might have seen this kind of praise for Chiang on Taiwan, but it would have been impossible to find on the mainland.

In the West, however, the living, breathing legacy of China’s wartime experience continues to be only poorly understood.

13

Many do not realize that China played any sort of role in the Second World War at all. Those who are aware of China’s involvement often dismiss it as a secondary theater. China’s role was minor, this assessment goes, and its government was an uncertain and corrupt ally that made little contribution to the defeat of Japan. In this view, China’s role in the war is a historical byway, not worthy of the full examination that is the due of the major powers involved.

One might guess that the West knows so little about China’s wartime experience because the events of the conflict took place far from American and European eyes and had little relevance for anyone other than the Chinese themselves. But this was not true at all. The reverberations of the all-clear signals wailing in Chongqing after the massive raids of May 3 and 4, 1939, were heard far beyond China’s borders. The agony of “Chungking,” as the city was then known in the West, became a symbol of resistance to people around the world, who were now certain that a global war could not be far off. At the time, the conflict between China and Japan was one of the most high-profile wars on the planet. W. H. Auden famously wrote a series of “Sonnets from China” in 1938, and one of them linked places “Where life is evil now./Nanking. Dachau.” For many progressives in the West, the war in China was linked inextricably with the Spanish Civil War, and many observers—Auden, along with his companion Christopher Isherwood, the photographer Robert Capa, and the filmmaker Joris Ivens—went seamlessly from one war to the other, reporting on them as connected sites in an overarching global struggle by democratic (or at least progressive) governments against fascism and xenophobic “ultranationalism.” In Britain, the China Campaign Committee raised funds for the defense of China. Even

Time

magazine’s Theodore White, later one of Chiang’s most powerful detractors, declared that the battle for Chongqing “was an episode shared by hundreds of thousands of people who had gathered in the shadow of its walls out of a faith in China’s greatness and an overwhelming passion to hold the land against the Japanese.”

14

And unlike Spain, where the war ended in 1939, the war in China became part of a global conflict that would engulf Asia and Europe too.

15

For almost any major country in the Americas, Europe, or Asia—the US, Britain, France, Germany, Japan—it would be ludicrous to suggest that the experience of the Second World War was

not

relevant in shaping that society in the years since 1945. From the United States’ sense of itself as global policeman, to Britain’s attempt to find a post-imperial role as a reluctant European state, to Japan’s desire to recast itself as a peaceful nation still living in the shadow of the atomic bombs, the war’s present-day legacy is clear. In contrast, the role of China, the very first country to suffer from hostilities by an Axis power, has remained obscure in the decades since 1945. Contemporary China is thought of as the inheritor of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, or even of the humiliation incurred by the Opium Wars of the nineteenth century, but rarely as the product of the war against Japan. Today, the names of battles and campaigns where China’s fate was at stake—Taierzhuang, Changsha, Ichigô—lack the immense cultural resonance of Iwo Jima, Dunkirk, the Bulge, Saipan, Normandy. Why did China’s wartime history fade from our memories, and why should we recall it now?

Put simply, that history disappeared down a hole created by the early Cold War, from which it has only recently reappeared. The history of China’s war with Japan became wrapped in toxic politics for which both the West and the Chinese themselves (on both sides of the Taiwan Strait) were responsible. All sides aligned their interpretations of the war with their Cold War certainties. Japan and China traded places in American and British affections between 1945 and 1950: the former moved from wartime foe to Cold War asset, while the latter changed from ally against Japan to angry and seemingly unpredictable Communist giant. The question of what had happened in wartime China became tied up in the US with the politically charged question of “Who lost China?,” and in the poisonous political atmosphere of the time it became nearly impossible to make a measured assessment of the contributions and flaws of the various actors in China. After 1949, in the newly formed People’s Republic of China (PRC), on the other hand, official histories were quickly revised to attribute the victory over Japan to the “leading role” of the Chinese Communist Party. The role of Nationalists was dismissed: it was stated that the wartime government had been more obsessed with fighting the Communists than the Japanese, and was anyway badly run, corrupt, and exploitative of the Chinese people. Scholars in Taiwan, where the Nationalists had fled after 1949, did argue against this view, but in turn their views were often perceived as suspect because they were produced under a dictatorship ruled by Chiang Kai-shek, who was still concerned to rescue his tarnished reputation. Furthermore, archives from the wartime period on the mainland were closed to scholars. As a result, the nuances required for an understanding of the period never emerged. Instead of tragedy, the war in China was painted as melodrama, with villains and heroes cast in black and white. All sides became convinced that the war was an embarrassing period, irrelevant to the supposed glories of Mao’s New China, but also of no interest to the West, which sought to forge a peaceful postwar world. Few wished to recall a depressing period that seemed to mark a low point in China’s long modern history of disasters.

Of course, it was not unique for any society to stress those parts of the wartime narrative that helped to build its own national self-esteem. Until the 1970s many Western histories of the war concentrated on the Western European front, downplaying the crucial contribution of Russia. In turn, Russia made extensive use of the “Great Patriotic War” of 1941–1945 at all levels of society to remold itself in the postwar era and to seek gains in the international community. In contrast, the war against Japan was used very selectively as a national rallying point in postwar China. When the wartime period was referred to in public, the only parts of the experience that were discussed in detail were the events in the revolutionary base area with its capital at Yan’an (Yenan), where Mao had pioneered a peasant revolution. There was no mention of the bombing of Chongqing; of wartime collaboration with the Japanese; or of the alliance with the US or Britain. There was not even much discussion of Japanese war crimes such as the Nanjing Massacre.

This situation changed radically in the 1980s, however. The People’s Republic of China reversed most of the key parts of its narrative about the war years. The party decided to revive memories of the wartime period, when Nationalist and Communist fighters had stood together to battle a foreign invader, regardless of party differences. New museums of the war sprang up to commemorate Japanese war atrocities, including Nanjing; movies and other museums gave the Nationalist military a much more prominent role, moving away from the ahistorical position that the CCP had been in the forefront of wartime resistance; and huge amounts of new scholarship poured forth, using archives and documents that had been locked away for decades.

This book is a beneficiary of the remarkable opening-up process in China. The new understanding of China’s role in the Second World War is not the product of a Western historical agenda being imposed on China, but draws on major changes within China itself. It is high time for a comprehensive and complete reinterpretation of China’s long war with Japan, and of China’s crucial role in the Second World War. Now that the Cold War is over, the question is no longer “Who lost China?,” with its implication of Communist infiltration and McCarthyism; but rather, “Why did the war change China?,” a more open-ended and fruitful question that avoids questions of blame and instead looks for causes. It also moves the debate away from being primarily about the American role and places the emphasis much more on China itself.

The ability to reinterpret the story of China’s war with Japan enables us to move away from melodrama. Instead, the war should be understood as a disruption to a much longer process of modernization in China. By the 1930s, after nearly a century of foreign invasion, domestic strife, and economic uncertainty, both the Nationalists and Communists wanted to establish a politically independent state, with a government that penetrated throughout society, and a population that was stable, healthy, and economically productive. It was the Nationalists who first tried to achieve those goals, in the decade before the war broke out in 1937. But the Japanese invasion made it almost impossible for them to succeed: from tax collection to provision of “food security” to the ability to cope with massive refugee flows, the problems were probably too great for any government to manage successfully. The war, then, marks the transfer of power to the Communists, but there was nothing inevitable about the process. And for much of the early part of the war, before Pearl Harbor, there was an alternative: the possibility that Japan might win, and that China would become part of a wider Japanese Empire. A new history of China’s wartime experience must take account of the three-way struggle for a modern China: Nationalist, Communist, and collaborationist.

Such a history must also restore China to its place as one of the four principal wartime Allies, alongside the US, Russia, and Britain. China’s story is not just the account of the forgotten Allied power, but of the Allied power whose government and way of life was most changed by the experience of war. Even the massive loss of life in Russia that followed the German invasion in June 1941 was less transformative than what happened to China in one fundamental sense: the USSR was pushed to its ultimate test, but did not break. It fought back and survived. In contrast, the battered, punch-drunk state that was Nationalist China in 1945 had been fundamentally destroyed by the war with Japan. Western condemnations of the Chinese war effort, and the role of the Nationalists in particular, have been based on accusations that the regime was too corrupt and unpopular to engender support: a popular American wartime joke declared that the Chinese leader’s name was really “Cash My-Check.” The truth was more complex: the Europe First strategy meant that China was to be maintained in the war at minimum cost, and Chiang was repeatedly forced to deploy his troops in ways that served Allied geostrategic interests but undermined China’s own aims. The crippled and unsympathetic Nationalist regime that limped to peace in 1945 was not a product of blind anti-communism, refusal to fight Japan (a bizarre accusation considering the Nationalists’ role in resisting alone for four and a half years before Pearl Harbor), or foolish or primitive military thinking. The regime was overwhelmed by external attack, domestic dislocation, and unreliable Allies.

China’s war with Japan also repays reexamination because wartime conditions shaped society in ways that have persisted even to the present day. Constant air raids made it imperative that people should live and work in the same spot, as it was dangerous to move around; after 1949, “work units” would impose a similar system across China which would not be dismantled until the 1990s. Chinese society became more militarized, categorized, and bureaucratized during the harsh years of war, when government struggled to keep some kind of order in the midst of chaos. These tendencies, along with an almost pathological fear of “disorder,” continue to shape the official Chinese mind-set. The greater demands that the state made on society in wartime also created a reverse effect: society began to demand more from government. The war saw extensive experiments in welfare provision for refugees, as well as improvements in health and hygiene. Other societies at war, notably Britain, found that they had to promise a welfare state to repay the population for the suffering it had endured during the war. But in the end, the Nationalists had created demands that only the Communists would be able to satisfy.

16

In the early twenty-first century China has taken a place on the global stage, and seeks to convince the world that it is a “responsible great power.” One way in which it has sought to prove its case is to remind people of a time past, but not long past, when China stood alongside the other progressive powers against fascism: the Second World War. If we wish to understand the role of China in today’s global society, we would do well to remind ourselves of the tragic, titanic struggle which that country waged in the 1930s and 1940s not just for its own national dignity and survival, but for the victory of all the Allies, west and east, against some of the darkest forces that history has ever produced.

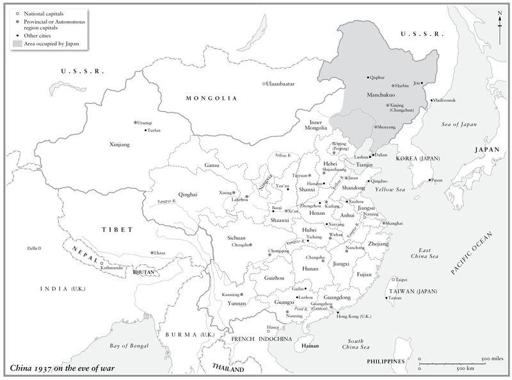

Maps