Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 (55 page)

Read Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 Online

Authors: Rana Mitter

Colonel David Barrett (left) and diplomat John Service outside their Yan’an lodgings. The two were part of the American “Dixie Mission” into Communist territory.

Song Meiling (Madame Chiang) on the rostrum of the US House of Representatives, Washington, January 18, 1943. US aid was critical to China’s war effort, but Chiang’s reputation faded during the war, despite Song Meiling’s attempts to restore it.

(

left to right

) Chiang Kai-shek, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Song Meiling at the Cairo Conference, 1943. This was the first (and only) conference in which China participated as an equal Allied power.

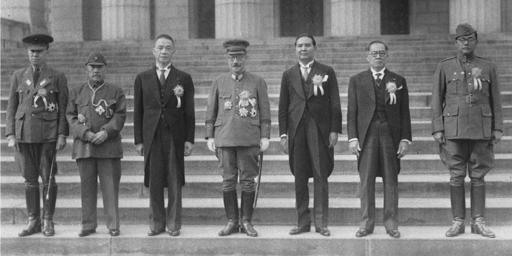

Participants in the Greater East Asia Conference, Tokyo, November 1943 (

left to right

): Ba Maw, Zhang Jinghui, Wang Jingwei, Tôjô Hideki, Wan Waithayakon, José P. Laurel, Subhas Chandra Bose. The conference aimed to project an idea of a Japanese-dominated Asia in contrast to the Allied vision for the region.

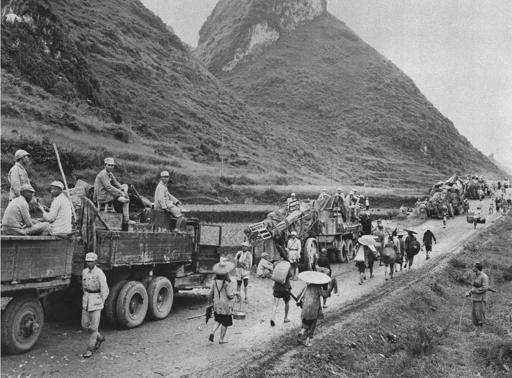

Refugees on foot, November 1944. The Japanese Operation Ichigô tore through central China in 1944 and devastated huge areas that had been held by the Nationalists.

Chinese-manned American tanks enter Burma, January 1945. The Allies had insisted on Chinese participation in the recapture of the country they had lost in 1942.

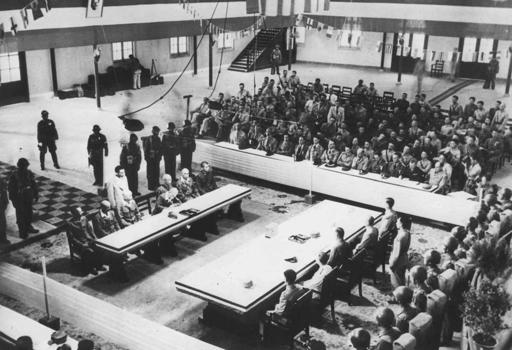

General Okamura Yasuji, head of the Imperial Japanese Army in China, during the surrender ceremony, with the Chinese delegation under General He Yingqin, Nanjing, September 9, 1945.

(

left to right

) Zhang Zizhong, Mao Zedong, Patrick Hurley, Zhou Enlai, and Wang Ruofei, en route to Chongqing for negotiations with Chiang Kai-shek after the Japanese surrender, 1945.

Chinese paramilitary policemen carrying wreaths of flowers march toward the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall in Nanjing on December 13, 2012, to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of the atrocity.

Anti-Japanese demonstration during the Diaoyu islands dispute, Shenzhen, September 16, 2012.

Chapter 17

One War, Two Fronts

H

UANG YAOWU’S FIRST AIRPLANE

flight took place in a troop convoy to India in June 1944. He knew that the Hump flight was dangerous, but he was young, ready for adventure, and not overly concerned. What bothered him much more was the cold. On the ground, the temperature was high, but in a Douglas C-47 Dakota some 9,000 meters above ground the soldiers were all chilled to the bone, wearing just one layer of clothing. “I was dizzy, my head pounding,” Huang recalled. Miserable, he fell asleep, with only the warm air on his body alerting him to their final arrival in India.

1

Huang’s Cantonese parents had immigrated to America but had returned to China after 1911, fired by a desire to help build the new republic. Huang had been born in 1928. His parents died early in the war, and needing to support himself, he signed up for the army, aged only fifteen. He had vivid memories of the early days of his service. His group of recruits sat in front of pictures of Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Zedong, and He Yingqin, placed on the wall as if they were all members of the same party and the bitter conflicts of the 1930s had never happened. Later, he and his friends went out into the mountains and swore blood brotherhood with each other, vowing never to return home until they had killed all the Japanese invaders. Within a few months, Huang would play a crucial role in one of the most heroic and tragic years in China’s war against Japan.

China would fight on two fronts. Although on one front it would win a tainted victory, on the other front it would face a disaster that would come close to destroying the Nationalist state. On New Year’s Day 1944 Chiang had sent a telegram to Roosevelt, warning that the strategy decided at Teheran, reversing the one proposed at Cairo, would provoke the Japanese to seize their chance in China. “Japan will rightly deduce that practically the entire weight of the UN forces [i.e., the Allies] will be applied to the European Front, thus abandoning the China Theater to the mercy of Japan’s mechanised land and air forces,” he declared. “Before long Japan will launch an all-out offensive against China.”

2

Western intelligence sources disagreed, convinced that the Japanese would take a more defensive position. At the Fourth Nanyue Military Conference in February, Chiang expressed his frustration that his position was not taken more seriously by his allies. “They do not consider the Chinese army to stand equal,” he admitted. “This is the most shameful thing . . . The basic reason is that our army is still not strong enough.”

3

By the spring, there were signals that something was brewing in east China. The American ambassador to China, Clarence Gauss, informed Secretary of State Cordell Hull on March 23 that credible intelligence indicated that “Japan is preparing for new drive in Honan.”

4

But General Stilwell’s attention had turned in a different direction. On February 14 a scorching article had appeared in

Time

magazine, discussing the opening of a supply road from India to Burma: