Forgotten Voices of the Somme (34 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

The shattered remains of Mouquet Farm. Pronounced Mucky Farm by the British, and Moo-cow Farm by the Australians.

There was a terrific amount of shelling going on. Then there came a lull, and we decided to go to this ridge. We crouched down as low to the ground as we could, he carrying his telephone and telephone line, and we dashed into this little valley in front of no-man's-land.

The valley was filled with dead and dying, who had failed in their assault that morning. It was

pathetic

. I remember, particularly, a sergeant. He was lying on the ground, dead, and he had his hand on his Bible. Open. It was a Douai Bible, and from that I knew he was a Catholic. There was shrapnel pouring over our heads. It didn't matter. I took his address from that Bible, closed his eyes, closed the book, put it in my pocket, and then we crawled back to the front line.

I sent that Bible home to his widow, and I kept up with her for quite a long time.

Second Lieutenant Tom Adlam VC

7th Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment

The attack on Schwaben Redoubt was going to be, I believe, at one o'clock. Our company had done most of the fighting the day before. They put us in the last line of the attack. And three other companies were in front. But we got in position at twelve, and we chattered away to keep the spirits up. You see, waiting for an hour for an attack is not a very pleasant thing. We told dirty stories and made crude remarks. I remember quite well that there was a nasty smell about. And, of course, we all suggested that somebody had had an accident. But it wasn't. It was a dead body, I think. Well, we joked in that way, in a rather crude manner, to just keep alive.

And then when the shells started they put everything in. You'd never think anything could have lived at all in the bombing that went on at Schwaben Redoubt. And the old earth piled up. And we went forward. And you'd see one lot going to a trench. Then another line going to a trench. Three lines had all met and mingled together. Some of them were killed, of course, so they weren't so strong as when they went in. And then we caught up with them, and by the time we got quite close to the Schwaben Redoubt, there was a huge mine crater there, about fifty feet across. And it was all lined with Germans, popping away at us. So I got hold of the old bombs again, and started trying to bomb them out.

After a bit we got them out of there, and we started charging up the trench,

all my men coming on behind very gallantly. And we got right to within striking distance of Schwaben Redoubt itself. Just at that minute, I got a bang in the arm and found I was bleeding. So having been a bombing officer who could throw with both arms, I used my left arm for a time. And I found I could bomb as well with it as I could with my right.

We went on for some time holding on to this position, and working our way up the trenches as far as we could. And when we were going along the trenches, the men would lose all control. There was a German soldier just at the dugout. He'd been wounded. He was in a bad way. He was just moaning 'Mercy

kamerad

! Mercy

kamerad

!' And this fellow in front me – one of the nicest fellows I had in my platoon – said, 'Mercy, you bloody German? Take that!' And he pointed point-blank at him. But he jerked, and he missed him. And I gave him a shove from behind, and I said, 'Go on! He won't do any harm. Let's go and get a good one!' But it was so funny, the fellow said afterwards, 'Sir, glad I missed him, Sir.' It was just in the heat of the moment, you see.

And then my commanding officer came up, and he said, 'You're hurt, Tom!' I said, 'Only a snick in the arm.' And he said, 'Let's have a look at it.' And he put a field dressing on it. He said, 'You go on back, you've done enough.' And so I sat down for a time. And the fight went on. But what happened afterwards, how they did actually catch Schwaben Redoubt, I don't know.

Major Alfred Irwin

8th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment

We were to go and occupy the Schwaben Redoubt on the night of September 29. We went on to ground that was utterly unrecognisable. Staff officers, back in comfortable offices, had detailed us to certain parts of the line that simply weren't there. There was a quarter moon, and very little light at all.

Whiteman

, one of my best subalterns, was commanding his best company, and when he'd got into what he thought was the correct line of trenches, he was heavily attacked by the Boche with flame-throwers, and driven back for some distance, but he led a counter-attack himself. He was a powerful man and a very good bomb thrower, and he got it all back again.

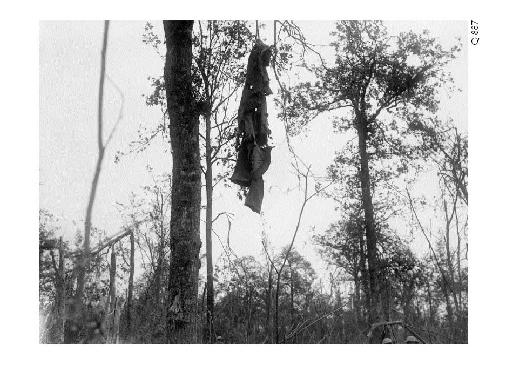

A German soldier's overcoat hangs suspended from a tree.

A dead German soldier lying outside his dugout.

Second Lieutenant Tom Adlam VC

7th Battalion, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire

Regiment

My commanding officer said, 'You've got to go back. Take this batch of prisoners back!' So I took about a dozen prisoners back with me. They filed in front of me. They were all unarmed. And I just had my old gun. I came to a little dugout, and there was a body lying on the floor there. I said, 'Why is that stiff down there? Why don't you get him out of the way?' 'He ain't a stiff, sir. He got at the rum jar. He's tight as an owl.' He looked dead.

You know they say the shell-holes were full of water? Well – they were full of blood and water. Everywhere was crimson, you see.

Haig had never lost sight of his hope for a breakthrough to end the attrition. The enemy third-line trenches had now been taken and, believing in an imminent German collapse, Haig planned a sweeping advance on

Bapaume

, and from there on to

Cambrai

to join up with a simultaneous advance to the north. At the beginning of October, however, heavy rain started to fall, which within days had turned the ground to glutinous mud. As conditions became difficult, so casualties continued to mount. And whilst the Germans were being pushed – slowly – back, and their morale was undoubtedly low, they continued to fight doggedly. The resistance encountered in the Schwaben Redoubt is testament to the German soldier's tenacity. The weather and an unreasonably obstinate enemy forced Haig to delay his plans.

Nevertheless, the offensive momentum was maintained. Prisoners were taken, and Le Sars was captured on October 7. The next day, however, the 1/5th Battalion,

London Regiment

was cut to pieces whilst attacking west of

Le Transloy

. As the weeks passed, and the weather worsened, so British morale fell and continued attrition seemed inevitable.

Nevertheless, on October 26, Haig formulated plans for another offensive. He would have to wait until the weather improved, but attacks

continued in the meantime. On November 5, the 16th Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps attacked near Le Transloy, achieving its objective. Three days later, Haig set the date of his final push for November 13. His objective was no longer a breakthrough – he would now settle for an advance of a thousand yards. With an eye on an upcoming Allied military conference, he wanted the British army to give a good account of itself.

The Battle of the Ancre lasted five days. On the first day, the Hood Battalion of the

Royal Naval Division

took Station Road, south of Beaumont Hamel (which was also taken – almost five months after it had been first attacked on July 1), and the

Seaforth Highlanders

captured Y Ravine within the German lines. Beaucourt was taken on the second day, by the

63rd Division

.

As the battle drew to a close, so the temperature fell. The final assault of the battle was launched in whirling sleet. The 8th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment, the battalion that had punted footballs towards the German lines back in July, now attacked the snow-covered

Desire Trench

. On the following evening, the

19th Division

failed to take the village of

Grandcourt

and, with that final action, the Battle of the Somme came to an end.

Corporal Don Murray

8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

On October 1, there was a lot of German prisoners coming down, and they'd built a special marquee for them. And this fellow said, 'Hey, Yorkie, there's a lot of Germans coming down, and they've been out in no-man's-land for a long time. They're nearly all wounded. Get jugs of hot tea and coffee, but don't give a drink to anyone with a body wound! Only to those with superficial wounds!' So I went into this marquee, and the place stank! Oh, it was awful! You know when you've had a sore finger, and you've bandaged it, and it's white when you take the bandage off? Well, they were like that, all over! Their face and everything. Wrinkled and white, from being out in the open. They were saying, '

Kamerad! Kamerad! Trinken! Trinken

!' And I didn't look whether they had body wounds, or what; I gave them their hot drink.

The next morning, I was told that they all had to have their boots taken off. They had no socks on – just rags on their feet. I said, 'I'm not doing that!' I was told, 'No,

you

don't do it! Get a big German out, and get him to bend

down, and the one with the boots puts his foot on his backside, and a third one pulls the boot off!' 'How do I tell them that in German?' I asked. 'Oh, it's easy. Just say, "

Stoopen! Stoopen

!" ' I believed it, too!

Anyway, there was one man who'd been mouthy all night. He'd been shouting, and going on, and I didn't know what he was on about. I called him out, and he came and stood to attention, and I said, '

Stoopen!

' '

Stoopen?

' he said. In the end, I bent him over and showed him what I meant, then I called the smallest one out and demonstrated what I wanted. Every time he pulled a boot off, he turned round to me; I thought he wanted to eat me! He was shouting at me, and going on, and all the prisoners were laughing. For all that they were so ill, they were laughing their heads off. Then, the parson came in the door, and he started laughing as well. 'Look, padre,' I said, 'there's such a joke going on here, and everyone's having a good time, but me!' 'It's no wonder!' he said. 'You've got the colonel pulling their boots off!'

1/5th Battalion, London Regiment

The night of October 8. As we went towards the front line, there was literally hundreds of bodies we passed, of all different regiments. You could tell from their uniforms and regalia. They had died on the first few days of the July advances. We went up though the communication trenches, up to the front line, and you saw dead men and pieces of limbs sticking out of the trench. To us young soldiers, it was very disconcerting.

So we went up. Each of us was taking it in turns to do sentry duty. That's staying on the fire-step, while the others lay about in the trench, best they could, and tried to get as much rest as they could.

I was resting on a box, and I woke up with a shot. I looked round, and there was a corporal laying down in the trench, with one hand hanging off, his face was spattered with pock-marked pieces of shell, and one ankle almost severed. I looked round and I saw another chap, who'd been sitting at the end of the fire bay. His head was blown off.

What had happened was that one of Jerry's shells had come through just where this chap was sitting, come straight through the parapet, taken his head right off, and burst in the trench. There were several other people wounded as well, but I was astounded because I wasn't touched.

I'd had training in first aid, as a stretcher-bearer, so I started patching this

chap up. I made a tourniquet and stopped the bleeding. Then an officer came along and gave him a tablet of morphine. Officers used to carry these things in their pocket. Anyone who was wounded, to take the pain away, they'd put this little sweet on their tongue, and they sucked it, and it sort of sent them off into unconsciousness. We got this chap on a stretcher, but we had to leave him there because word got around that, at three o'clock in the afternoon, we was

going over the top

.