Forgotten Voices of the Somme (30 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

Private William Holbrook

4th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

We were sent to the trenches

at Delville Wood

on July 22, and as our company were making its way there, along the cart track, in the dark, an officer named

Lieutenant Cook

came and told us that this was a hell of a place. He

said, 'Make very little noise. There's a German machine-gunner a hundred yards to your right. Any noise you make, you'll be under fire, so be as careful as you can.' He'd only just said these words, when a lot of Very lights shot up in the air. It was just like daylight. We didn't know what had happened, or where they'd come from. And the machine gun opened up on us, and they started shelling us, and about ten of us were killed. I went to help the wounded, and I saw one man lying on his back and I recognised him. I hadn't seen him since I joined the army, as a boy, back in 1908. And there he was, lying badly wounded. I bent down and he looked up – I know he recognised me – but he died. He was in my company and I didn't even know it. We found out what had happened. A fellow was carrying all these Very light pistols in his pack, and something hit his pack and set them all off. And turned everything to daylight.

When we got to the trenches at Delville Wood, we'd never seen anything like it. There was no entrance to the trench, and we had to slide in over the side. There was thick mud, and there were bodies lying everywhere. There were no duckboards, and the bodies squelched under you as you walked along. It was one hell of a place. I was orderly to our company commander, Captain Sparks, and when he saw that there was a fifty-yard gap between our lines, he said to me, 'I'll go along and see what I can do to close this gap.' I asked him if I should come with him, but he said, 'No, see what's been left behind. See if you can find anything to drink.' So he went off, and I looked around, and I found some concentrated cocoa and I started to make it up.

Captain Sparks

was a long time coming back, and I stopped someone and asked where he was, and I was told that he'd been killed. Killed by a whizz-bang.

We were holding the trench under heavy rifle fire, and I was told to take a message back to

Carnoy Valley

. So I left the Delville Wood trenches, and I was creeping along this ground when I met another fellow going down and we went on together. We came to a sunken road where we found over a hundred British troops, all lying dead. They were black from the sun. No one had ever found them. There was one man lying on a stretcher with one leg missing, and holding each handle of the stretcher was a dead man. All of them must have been killed by the same shell.

22nd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

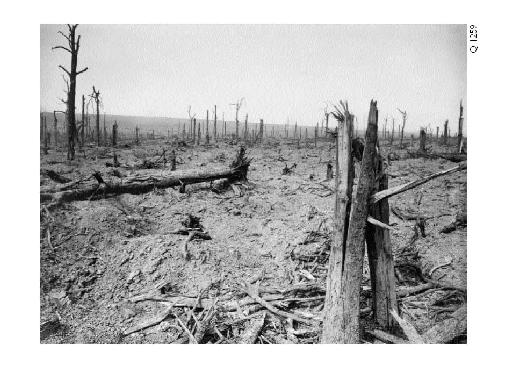

Delville Wood was a beastly place. It was badly mutilated. The trees were stumps. The fighting was going on in the wood itself and it was taken, back and forth, several times. There were extremely heavy casualties, and I don't remember there being a proper line of trenches. There were bodies lying around the place – quite horrifying. I can remember stepping over them, in order to advance. I remember being given instructions to retire, and we having to move back several hundred yards.

Lieutenant Duce

1st Battalion, Royal West Kent Regiment

We were detailed to go over the top, in an attack on High Wood, on July 23. I had Number Five Platoon, B Company, and we were detailed to go all the way through. I was darned annoyed because I was going over first. We were to go over at three-fifteen on Sunday afternoon, and while I was waiting there was nothing to do but go to sleep, and I found that I was able to sleep at the side of the trench. When we went over, I was quite fortunate. Of the three officers of my company, two were killed and I was only wounded. Out of 480 men, 160 were killed, 160 were wounded and 160 got through. It was rather extraordinary. As I was stepping over the wire, I was shot straight through the foot, which knocked me down. If I'd put my foot down before, I'd have got it right through the knee. I laid out there for some hours, and then as I started to crawl back, parallel to the German line, a German came over the top and stood, looking out, holding his machine gun. I just had to freeze. I can tell you, it's quite a nervous tension to lie there for ten minutes without moving, so that he thinks you're a dead body. Gradually, I turned my head round to look and saw that he had gone, and I crawled back. As I was crawling back, I followed a small trench and I came across a dead man in the trench. All I could do was crawl straight over him. It wasn't a pleasant thing.

2nd Battalion, 1st Division, Australian Imperial Force

Without doubt, Pozières was the heaviest, bloodiest, rottenest stunt that ever the Australians were caught up in. The carnage is just indescribable. As we

Delville Wood. A beastly and mutilated place.

were making our attack, we were literally walking over the dead bodies of our cobbers that had been slain by this barrage.

I can't imagine anything more concentrated than the artillery barrage of the Germans at that particular stunt. The bay on our left went in, two or three chaps were killed; the bay on our right went in. I said to this chap, 'It's our turn next!' I hadn't said it before we were buried. I was quite unconscious, buried in what had been the German front-line trench.

Lieutenant William Taylor

13th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

The woods had been very much knocked about. We took up a line of trenches – quite good old German trenches – on the edge of High Wood, waiting for instructions as to whether to attack or whether we merely had to defend. We were there for about a week. During that time, apart from being shelled, there was no action. The Germans did not counter-attack, and we were not ordered to attack further. One had no idea of the general strategy as to what was going on along the front. You might get orders to attack in the morning, or you might get nothing at all. One never knew. We couldn't see the German front line at all. We were facing the wood, about two hundred yards from the wood, and the German line must have been the other side of the wood, because we couldn't see them at all.

While we were there, we were improving our defence all the time. I can remember receiving a note from the adjutant one night, telling me that we had to work all through the night to strengthen the wire in front of our trench, and that it would be brought up by a fatigue party, dumped at a certain spot on our line, and we had to put this wire up during the night. We did it all night. After all, these were ex-German trenches and any wire we had was on the other side. We were wide open. It was barbed wire and concertina wire with the usual corkscrew stakes that we screwed into the ground, and trained the wire. I was commanding the company (my company commander had been hit) and I suppose that we had sixty or seventy men only. So we all worked on the wire, the whole night long. We weren't shot at. I don't think we had any casualties. We had no intention of staying there for a period, so the latrines weren't dug at all. There were plenty of shell-holes in the area, and we used those. Any dead bodies had been buried.

There had been severe fighting in High Wood early on, and every day we

expected that there might be a counter-attack by the Germans. But nothing happened, other than shelling. We had a certain number of casualties, wounded by shelling, but I don't think we had any killed. I was promoted to acting captain, and I was commanding the company whilst we were in High Wood, but some weeks later, when we were behind the line, an officer came from another company, who was senior to me. He took over. I was disappointed, but I was still a second lieutenant, and he was a lieutenant. He'd been on the Western Front longer than I had. But there were other occasions when I was commanding the company, and a captain came out from home, who hadn't been out before, who had been promoted whilst at home, and I had to hand over to him. One was very upset about it. It happened again and again, and I rather resented it.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

On the night of August 4, we moved up to what I now know was the Pozières Ridge. Just imagine a huge saucer, and the lip of the saucer was the ridge, the village of Pozières was over the top of the ridge and it was known as the Pozières Ridge. Whoever held that ridge – at that time it was the Germans – overlooked a huge part of the whole Somme battlefield so it was very, very important that this should be taken.

So that night, we were moved up into a newly dug slit trench. Our objective was uphill, somewhere between two hundred and three hundred yards. We lost a few men going up the communication trench – but not many. When we got into this assembled trench we settled down there, sat down on the bottom, and the order came, 'Platoon sergeants to come to headquarters.'

Company headquarters was in the same trench, and we went along, and there was

Captain Cazalet

, and this is the sort of order we got: 'It is now eightfifteen, at nine o'clock we go over the top. We're going behind curtain fire.' Curtain fire was shrapnel bursts, and as you advanced the guns went farther in front. You advanced behind a 'curtain of fire', you see. Captain Cazalet went on, 'I will go over with the first wave, and

Mr Firefoot

, the second in command, will go over with you, Sergeant Quinnell. You'll be in the second wave. Now go along and tell your men to be ready and as soon as the curtain fire starts, we move.'

Back along the trench we went, and I told the men what to do. I gave them

the tip, 'Run like hell, and catch up with the first wave!' That wasn't an order – it was just a tip because my experience told me that when you're out in noman's-land, you're standing there naked, but if you catch up with the first wave, the sooner you'll get your job done and the fewer casualties you'll have. So that's what we did. We caught up with the first wave behind this curtain fire, and we were into the Germans with the first wave. We ran like hell, too.

When we got to the German trench, there was this German kneeling on the floor of the trench and the poor bugger was dead scared. While I'm standing, wondering whether to stick him or shoot him, a German jumped out of the trench away to my left, and another one to my right, so I jumped down on top of this German, pinned him down, knelt on his shoulders, shot the German on the left, worked my bolt, put another one up the spout and shot the German who was running away on the right.

By this time, all our men had reached the trench and I went along to report to the captain that we'd arrived. He said, 'Good, now let's have a quick rollcall.' So I counted my men and I'd only lost three coming over, which was a marvellous performance. It was the surprise attack, you see. The Germans didn't have time to drop their barrage down. But once we were in the German trench, the barrage came down behind us, and my tip of getting my men to catch up with the first wave paid off, otherwise they would have caught the barrage.

The battalion on our left had not got through, the companies on the right of our battalion had not got through, and we were the only battalion to get our objective. So we had a quick consultation, two platoon sergeants, Captain Cazalet and Mr Firefoot, his second in command, and it was agreed that we'd make a barricade on our right flank and a barricade on our left flank and hold it.

This we did, but all this time we were being sniped at from behind. We expected the shots from the front, but we were being sniped at from behind as well. We thought it was our own people sniping at us. In fact, there was over a hundred Germans in a little slit trench that we'd jumped over.

On the morning of August 5, we had our first experience of

liquid fire

. Over the barricade on our right flank came a German with a canister of liquid fire on his back, squirting it out of the hose. He burnt twenty-three of our chaps to death. I plonked one into his chest, but he must have had an armour-plated waistcoat on. It didn't stop him, but somebody threw a Mills bomb, which

burst behind him, and he wasn't armour-plated behind so he went down. But he'd done a lot of damage. Plenty of our chaps were wounded, as well as those that were killed, and it practically wiped out

Tubby Turnbull

's platoon.

Then we got an order from the captain. I hope I never hear it repeated. He gave us an order to make a barricade of the dead – the German dead and our own dead. We made a barricade of them and retreated about forty yards back. I'd got a barricade on my left to look after, there were plenty of Germans to the front, and the sniping from behind, so we had to have our sentries facing both ways. And this barricade of the dead. We only had two bombs apiece, in our tunic pockets. Everybody handed their bombs in to the right-hand flank because we decided it was the danger point, and all our bombs were taken along to the barricade there.

Over the next three days, we would face five attacks either at dawn or dusk from over this barricade, but that afternoon the Germans in the trench behind us were winkled out, and that night our pioneer battalion dug a sevenfoot deep communication trench, hundreds of yards, from the old British front line to where we were. As soon as that trench was dug, up came a

Stokes

trench mortar with plenty of rounds of ammunition, and a specially trained crew. As well as boxes and boxes of rifle grenades.