Forgotten Voices of the Somme (28 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

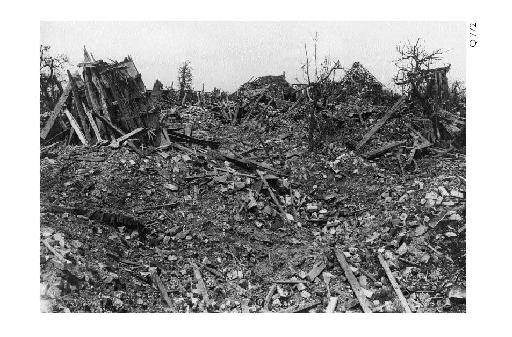

Destroyed German barbed wire with Mametz in the distance.

The shattered remains of Mametz.

bottle full of rum. He poured it down me. I was spluttering, and it cut whatever was in my throat. I was able to breathe again.

On July 14, the planned assault (which came to be known as the

Battle of Bazentin Ridge

) was carried out by five divisions, with the intention of securing the positions between

Delville Wood

and

Bazentin-le-Petit

. In addition, the

2nd Indian Cavalry Division

was ready to advance quickly through any breaches in the German lines. In a change of tactics, the attack was preceded by a five-minute 'hurricane' bombardment of highexplosive shells. The lesson had been learnt that a shrapnel barrage did not cut wire. Other lessons had been learnt; in this attack, more emphasis was placed on a creeping barrage – moving forward fifty yards every minute and a half – and in addition, the troops crept forward under cover of darkness to assume starting positions close to the German lines. The element of surprise that this provided would prove crucial. The German defenders were still climbing out of their dugouts when the trenches were stormed by the British attackers. As a result, the attack was a success. Four miles of German second-line trenches were taken. The cavalry, however, could not exploit the success, and was withdrawn on the following day.

Private William Holbrook

4th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

Before the attack on Bazentin-le-Grand, I felt a little bit shaky. I was always worried about being blinded. I'd seen people killed and wounded, and it didn't worry me, but I was afraid of being blinded. One fellow, a bit older than me, he started crying out during the shelling. I thought he was going mad; crying and shouting. There were people who were so shaky, they couldn't hold their rifles.

The fellow next to me was killed before he got over the top. He fell dead on the parapet. The battlefield was pretty flat. There were some factories on the right, and houses on the left, but we were concentrating on what was in front of us. There was some shelling, but the machine-gun fire was deadly. We had to hop from shell-hole to shell-hole. We couldn't make one run at it. A lot of

the Germans had gone back to another line, so we didn't get much resistance when we got there. When we got into the dugouts, we found a general and his staff inside, and they were in their pyjamas. They'd been asleep. We took prisoners and sent them back.

Corporal Henry Mabbott

2nd Battalion, Cameron Highlanders

After an attack, I brought a very young German boy, who had no uniform. When we got into our own front line, I piggy-backed him to the dressing station, and I got into trouble for it.

Signaller Leonard Ounsworth

124th Heavy Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery

We were out all day. We stuck the flag up at times to send messages through, and we got shelled. We went further along, and there were some parties of Jerries coming along with their arms up; well, we didn't want them. 'Go on! Bugger off out of here!'

And so we went on and on and night came. Well, we got no orders and we'd no water. We'd given it all to wounded men. So I found a field battery, and begged the sergeant major to let me fill up these water battles. I said, 'We're on forward observation about a mile up in front.' So I got them filled and then when I got back, the next thing I knew was a shell burst. It knocked the lamp out of my hand, and I'm left with the sending trigger, and that was the end of the lamp. I thought it was a bloody good job that we didn't have to do any more signalling.

We were out all that night, and the next day we'd no more rations, so we set off to come back. On the way, we picked up a field artillery lad; he'd got himself lost. So we walked on with him and it was reasonably quiet, but suddenly they started shelling us and we flung ourselves down, only we didn't get down quick enough, I suppose, because when we got up, the lad didn't get up. I could see a dull glow, and I said, 'Go and see if that's a dressing station,' and it was. It was an advanced field post, and we got a stretcher for the lad. I picked him up, and I thought, 'He feels funny,' and the captain in charge just put a blanket over his head. He was gone, and his blood had run off the stretcher on to my britches.

Well, it was a misty, dull morning, thick ground mist, you see, and we got

into Montauban. There was a dyke alongside the road, there were some fallen trees there, and we were under a big tree across the dyke. A blooming shell hit this tree and split it in half. Nobody got a scratch and we were covered with pulverised wood. It wouldn't come off your tunics. A yard or two either side, if it had missed the tree trunk and exploded in the dyke, we should all have got it.

We set off again. We were walking over this open ground and we heard a voice yelling to us, 'Get down, you silly so-and-sos!' So we dropped flat, and crawled up a bank, and we saw some infantry. It was the 8th East Yorks. There was about two hundred of 'em left out of eight hundred. They'd lost seventyfive per cent from machine-gun fire.

A little later we were in a shell-hole, and somebody was making a run behind, and he was hit right in the ear, and he pitched up amongst us, and just for a few moments – I suppose his heart was still beating – blood was spurting out of his ear, then gradually died away.

Well, then, the next thing was Jerry put a box barrage down, to cut off that section, so I said to this officer, 'We'd better get out of this, there'll be a counter-attack in a minute!' He wouldn't move, so I said, 'You bloody well stay there! I'm going!'

So we started crawling out. We had some rations with us. I had a sandbag with some tins of bully, and I put that across the back of my neck, and we were crawling flat on our faces to get through this barrage. It was shrapnel, fortunately, most of it going in the ground, not doing much damage.

Suddenly there's a terrific clout on the back of my head, knocked me out for a moment, and then I felt something move. What had happened – a big clod of earth had dropped on the back of my head as I'm crawling along, and bashed me. My nose was bleeding, my chin was cut, and we crawled on and got out of it.

We established another observation point, on a slope, for collecting information, and then on the far side we saw some infantry transport come up. There was a lieutenant quartermaster there, a man about fifty, not a fighting man at all. I went over and he said, 'How are you off for grub?' so I said, 'We've only got biscuits and bully,' and he gave us some bread and butter, jam, tea and sugar. He'd brought up all the rations, and he was practically in tears. He said his lads didn't need it. You see, the

Army Service Corps

in the back had sent up rations for so many men, and he'd lost half of his. What happens

to all that grub? You live like fighting cocks on what's left – for a day or two.

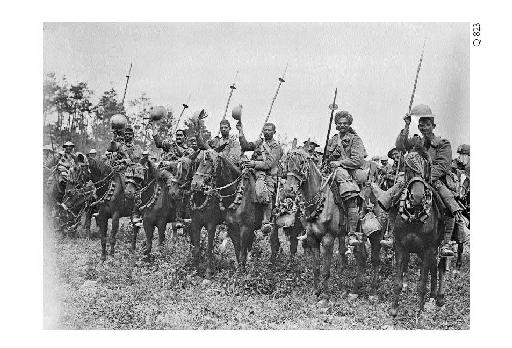

After that, I watched a

French

monoplane that kept diving down on to the corner of a field, as our cavalry – the

Deccan Horse

– approached. The plane kept on diving towards this corner and, suddenly, the officer in charge of cavalry cottoned on and he stood up in his stirrups, waved his sword above his head and charged across the field. The two outer lots of cavalry split, to make a pincer. The next thing we saw, they had encircled thirty-four Jerry soldiers, some of them with heavy machine guns, and taken them prisoner. The Jerries had been waiting, while the cavalry got nearer, and the plane had drawn their attention to the Jerries. It was over in a matter of seconds – but if it hadn't been for the plane – my God, it would have been slaughter.

After that, I saw some more Jerry prisoners coming back. Terrible really. There were about two hundred of them, and a score of our chaps, guards, on the side and in front. There was a big German officer out in front, a proper square-head, a bloke about six foot three, and he's walking behind one of our corporals, who was leading. The Jerry suddenly grabbed the corporal's rifle from behind. The corporal turned round and yelled to the other guards, who ran back a few yards and started shooting at the Jerries. That quelled the mutiny, but it was a stupid thing to do. The Jerries were all disarmed.

Mr Noble, Mr Robbins and myself went into Trônes Wood. Well – good God – there were no trees intact at all, just stumps, tree tops all mixed together, barbed wire, bodies all over the place, Jerries and ours. Robbins pulled some undergrowth up, we were having to fish our way through it, you see, and there was a dead Jerry, shot away right up his hip, and all his guts were out, and flies on it, and Robbins just had to step back. This leg that was up in the tree became dislodged, and that leg fell across him on his head. Good Lord, he vomited on the spot, terrible.

We were walking across this open ground between Bernafay Wood and Trônes Wood, and there's a big communication trench goes right across it, and I'd stopped to cut some brass buttons off a dead man's coat – I mean, he won't want them any more. We were getting by with composition buttons at the time, awful things, so I thought, 'I'll have those brass buttons,' and I cut them off, and I've just got them in my pocket when I heard Jerry was sending over harassing fire. I thought, 'God! This one's coming close!' You always marked the nearest hole to dive into, so I dived for this trench and flung

The Deccan Horse at Carnoy Valley on July 14.

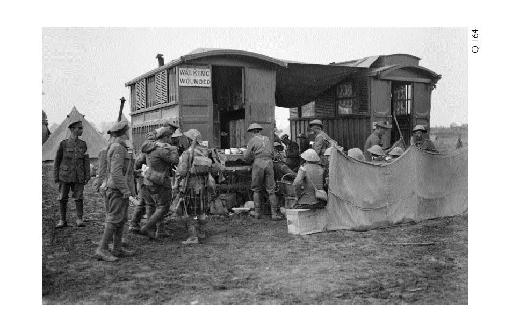

Refreshment caravans for the use of walking wounded during the Battle of Bazentin Ridge on July 14.

myself into it. And at that moment, a blooming shell landed in a corner of the trench. I'd have been better if I'd stayed on top.

Well, the blast blew me out of the trench. I bruised my hip on the edge of the trench as I flew out, and I landed two or three bays away. Mr Noble and Mr Robbins were in front, and they'd both dropped, and there was a huge cloud of smoke. 'By God,' I thought, 'that was bloody lucky.' They said, 'Are you all right?' I said, 'Yes,' and I started to walk after them.

I walked on a bit, and I felt my hand was wet, so I wiped it on my britches. There was blood running off my hand, so I thought, 'Oh hell!' I shouted to them, 'Half a mo' – I am hit after all!' and we sat down in a hole, and I got a field dressing from my tunic, and Mr Robbins started to bandage me up round my neck. I said, 'It's my arm,' and he said, 'No! it's here!' I didn't know it, but I'd got one through my jaw and one in the throat, just missed the jugular. I'd got another one in the back but they didn't find that till I got to hospital at Rouen. I'd stopped four pieces and never felt them. You feel it afterwards, mind you, but just at the moment you don't feel anything at all.

So then the two officers took me to an advanced field post, a dressing station in Bernafay Wood, and I was rebandaged there, and while we were there, there was a man brought in on a stretcher. They had to tie him down with wire on a stretcher; he'd got shell shock. God, he was raving mad.

When it got dark, I was put into a

horse

ambulance, a pair of horses, a covered wagon sort of thing, with two stretchers at the bottom and two stretchers at the top, and I was in one of the upper stretchers. From that point, we had to cross what had been no-man's-land for twenty-two months. Well, the road was in a hell of a state and this thing was lurching all over the place, and before long myself and the other lad on the top stretcher we were thrown into the floor. There was nothing we could do about it, and the driver got us to

Billion Wood

.