Forgotten Voices of the Somme (24 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

Sergeant Frederick Goodman

1st London Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps

When I first got to France, the very first time I saw real casualties, they were a German captain and one of our sergeant majors. They'd met each other over the top, they'd fired simultaneously and shot each other. I had to pick them up. We got them into the dressing station – and I fainted. It was the first time I saw blood in the 'real sense'. After that, I had to pull myself together, and as time went on I became quite callous. But we saw so much, and we had to get used to some very awful things.

Being a stretcher-bearer was a very arduous job. We had to carry stretchers for a hundred yards, up to our knees in mud, and there would be other men to take the man back to the advanced dressing station. And then, further back, there would be a main dressing station, and finally a casualty clearing station. There were times when we had so many casualties coming in at one time that we didn't always have adequate staff to deal with them. We did the best we could with them. We would do a first field dressing – rip up their tunic, and

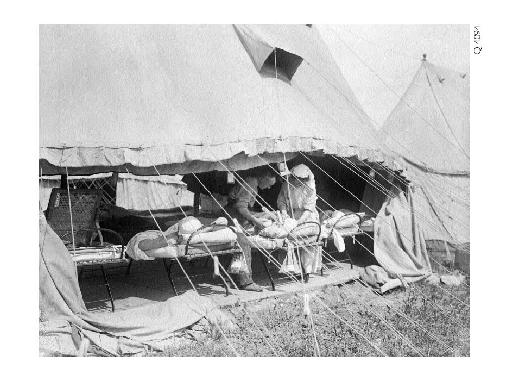

Stretcher-bearers bringing in a casualty.

An

advanced dressing station

at Fricourt.

whack on the dressing – but if it was more serious than that, we'd put them on a stretcher. We did the best we could.

I had a great friend at school, who was rather partial to my sister. He was a very discerning young chap! They got on very well together. Well, he went off to join Princess Louise's, the 13th London, and one day I was called to give some assistance, and one man had some shrapnel, so I ripped up his tunic and applied the necessary. And as I was doing this, he looked up and he said, 'Good Lord! It's you, Fred! Well, I'm damned!' It was the very same chap.

On one occasion, we had a small truce. We had so many dead over the top – and so did the Germans – that we called a truce. An hour or two would be allowed, to go over the top and bury the dead. This was carried out, and eventually someone started firing again and that was the end of that. And we had a message from headquarters, saying that they knew what had happened and they didn't approve of it. We were fraternising with the enemy – and that must not be! And I can understand it too! We didn't want to fraternise with them! But we had to attend to our chaps. There were so many dead. The memory of it is awful. Dreadful. You have no idea.

Lieutenant Phillip Howe

10th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment

There were so many casualties on the Somme that they wanted to get rid of them to England, to keep the

hospitals

in France empty as far as possible to deal with the really serious cases. Myself being only walking wounded, they shoved me onboard a boat, which was over-laden with wounded, and hundreds of German prisoners too. It was a very slow crossing from Le Havre to Southampton.

Private Harold Hayward

12th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

I got sent home to Blighty, and went to

Lincoln General Hospital

. I was very well treated, except for one thing. In this ward, there was a lady from one of the county families, who used to come once a week, and she was rather nosey. She wanted to know everything. At first I told her that I was wounded, but she said she couldn't see any bandages. Well, they were under the bedclothes. I pointed down there, hoping that would be sufficient. The next week she came back, and again she said, 'Where were you injured?' I knew what

A casualty clearing station near Vaux.

she meant, but I said, 'Guillemont.' 'No,' she said, 'where on your body are you wounded?' I was a bit fed up by now, and I said, 'Madam, if you had been wounded where I have been wounded, you wouldn't have been wounded at all.'

That was the last time she visited. Some of the men on that ward guffawed quite loudly – and she stormed out of the ward, and never came back.

Private William Holmes

12th Battalion, London Regiment

In hospital, in England, I was given what these drug addicts take now.

Heroin

. I was in such agony that I couldn't get to sleep, and the nurse asked if I'd like a cup of tea – and no sooner had I drunk it, than she put the heroin into my thumb. And the whole scene changed. My eyes were opened. I could see flowers about twenty-five feet high, lovely fountains. I felt

so

well.

Signaller Leonard Ounsworth

124th Heavy Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery

When I was out of hospital, I was sent before a Standing Medical Board in England. There were two or three officers there and you filed past them. They were examining about a hundred men in an hour. You went before them and they said, 'What's the matter with you?' and I said, 'Gunshot wounds in the arm, in the neck and the jaw and the back,' and they said I was all right; I said I couldn't open my jaws properly yet, so he then said to me, 'Well, go down to Market Square in Ripon this evening – do you know it?' I said, 'No, sir, I only arrived last night, in a snowstorm, in the dark.' 'So go down there,' he said, 'find the prettiest girl you can, take her down a dark passage and get her to tickle you under the chin. You'll soon open your jaw then.' That's the advice he gave me, 'Next one!', and I was bloody disgusted.

Private Harold Hayward

12th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

I had to report to

Horfield Barracks

, not two miles from my parents' home. I was being 'rehabilitated' and that really broke my

patriotism

. We were drilled up and down the square by these fellows who got at us. To think these people, who'd been in England, were doing this to us, who'd been out in the trenches, and they treated us as though we were less than the dust. I lost a lot of my patriotism then.

Major Alfred Irwin

8th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment

People in England had no idea whatsoever what was happening in France. I was sitting in a restaurant in London, with my wife. We'd been married a very short time. My wound was recovering, and I was still on medical

leave

. A girl came in, with

white feathers

, and I was in civvies. There was nothing to show that I'd taken any part in the war, and she presented me with a white feather. My wife was

so

furious.

Corporal H. Tansley

9th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

There were strikes going on in England at the time, because people were losing their pint of beer, or not getting this-and-that. They used to ask, why didn't we press the war and get on with it? Well, that showed a proper ignorance of the feelings of the soldiers at the front. We had pressures behind us that people at home could hardly dream of.

Second Lieutenant Edmund Blunden

11th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment

On leave [in 1917] I was asked to stay with some dear relations. They were very kind but they asked me how things were going. They pointed out the scale of the British victory. I had to confess that I didn't think that the victory amounted to very much since we hadn't got anywhere – and wouldn't. I gave an account of

Passchendaele

. This, I found, was a horrible offence against the natural order. My relative said, 'I fancy that this is quite enough, young man! You're fighting for the Germans! You'd better make up your mind where you'll be staying tomorrow night!' So I left the house under those conditions. That was a bit of a puzzle. It showed me that I hadn't been thinking enough of the people at home. Neither, for that matter, had they been thinking of us very much.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

The first night I came home to England on leave I got into my old bed and do you think I could sleep? No. Sleep wouldn't come. It was the first bed I'd laid in since I joined the army. And when my mother brought my cup of tea up in

the morning she found me fast asleep on the floor. I got so used to sleeping hard that I couldn't sleep on a soft bed.

30th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

On my first leave in England, there were two army nurses walking along, talking to each other, and so you know, I hadn't heard an English woman talking for fourteen months and I was so impressed and interested. I just walked behind them and listened to them talking. I don't know what they thought of me. I've never forgotten it.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

Life in France was a life apart from anything that you'd done in civilian life. You'd become a gipsy, you'd learned to look after yourself: whereas in your civilian life your mother did all the chores, now you had learned to do everything for yourself. You'd learned how to cook for yourself, make do, darn your own socks, sew on your own buttons and all things like that. You could speak to your comrades and they understood – but the civilians, it was just a waste of time.

16th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment

W

hen I was convalescing after July 1, I was home at my home in

Bournemouth

, and my father wanted to see the film

The

Battle of the Somme

, so we went to the Electric Theatre and we saw it. I saw the mine go up again – I had actually seen it go up! I saw our division being inspected by the general on the day before the battle. I didn't recognise anybody. We had known they were taking films, because we had seen them doing it. They'd had special places built to protect them from shells.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

I'd always been a great lover of the country and before the war I used to do a lot of cycling. Pretty well every weekend in the summer I'd be out cycling. And one of the first things I did, when I was home on leave, was to resurrect

my old bike, pump the tyres up, oil it and clean it, and I rode round the old country visiting the old scenes that I knew in peacetime. That to me was the most enjoyable thing.

Sergeant Frederick Goodman

1st London Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps

One day, my colonel said, 'You know, I can't give you any Blighty leave, but if you and your pal want some leave, I'm quite prepared to give you a fortnight's leave here in France. Would you like to take it?' 'My dear sir,' I said, 'I would! Of course!' 'Where would you like to go?' 'Sir, there's only one place I want to go! I want to go to

Nice

! The south of France!' I'd always liked the idea of the Promenade des Anglais. And they gave me a pass.

I wrote to

Thomas Cook

– they were in existence – and I told them that I wanted to go to a place where I'd be looked after in a hotel, but I didn't want to be subject to a lot of discipline from officers. In other words, I wanted them to put me in a sergeant's place, somewhere appropriate to me. Well, they did. They fixed me up with a private flat, attached to an English restaurant. A girl used to come in every day, and make the beds and do the chores, and my pal and I would go downstairs to have our meal. I went to

Monte Carlo

where I sent my parents a card, and we joined up with some Women's Institute-type ladies who invited us to their homes, and we met a couple of girls . . . We had a wonderful time. Why not? Wouldn't you?