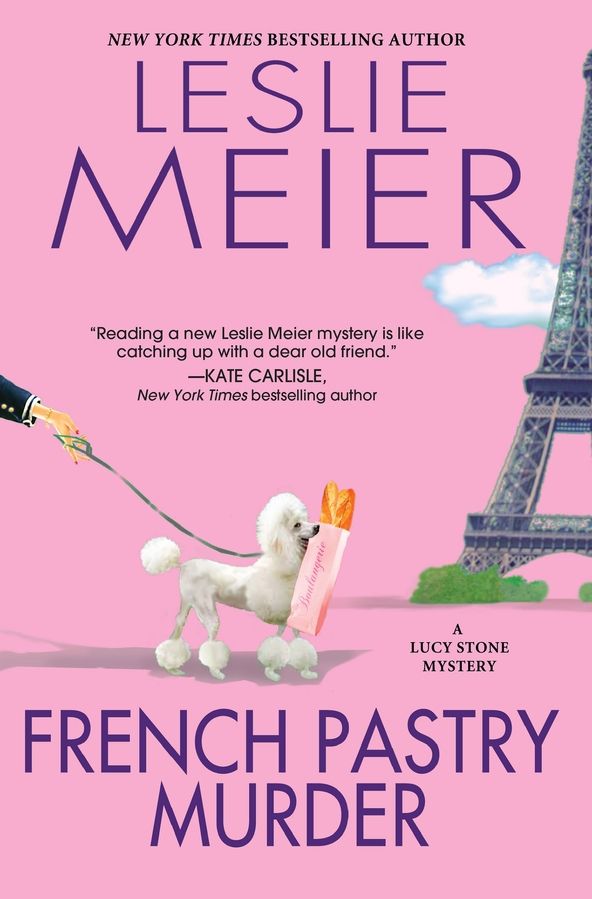

French Pastry Murder (A Lucy Stone Mystery)

Read French Pastry Murder (A Lucy Stone Mystery) Online

Authors: Leslie Meier

BOOK: French Pastry Murder (A Lucy Stone Mystery)

9Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Books by Leslie Meier

MISTLETOE MURDER

TIPPY TOE MURDER

TRICK OR TREAT MURDER

BACK TO SCHOOL MURDER

VALENTINE MURDER

CHRISTMAS COOKIE MURDER

TURKEY DAY MURDER

WEDDING DAY MURDER

BIRTHDAY PARTY MURDER

FATHER’S DAY MURDER

STAR SPANGLED MURDER

NEW YEAR’S EVE MURDER

BAKE SALE MURDER

CANDY CANE MURDER

ST. PATRICK’S DAY MURDER

MOTHER’S DAY MURDER

WICKED WITCH MURDER

GINGERBREAD COOKIE MURDER

ENGLISH TEA MURDER

CHOCOLATE COVERED MURDER

EASTER BUNNY MURDER

CHRISTMAS CAROL MURDER

FRENCH PASTRY MURDER

TIPPY TOE MURDER

TRICK OR TREAT MURDER

BACK TO SCHOOL MURDER

VALENTINE MURDER

CHRISTMAS COOKIE MURDER

TURKEY DAY MURDER

WEDDING DAY MURDER

BIRTHDAY PARTY MURDER

FATHER’S DAY MURDER

STAR SPANGLED MURDER

NEW YEAR’S EVE MURDER

BAKE SALE MURDER

CANDY CANE MURDER

ST. PATRICK’S DAY MURDER

MOTHER’S DAY MURDER

WICKED WITCH MURDER

GINGERBREAD COOKIE MURDER

ENGLISH TEA MURDER

CHOCOLATE COVERED MURDER

EASTER BUNNY MURDER

CHRISTMAS CAROL MURDER

FRENCH PASTRY MURDER

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

A Lucy Stone Mystery

FRENCH PASTRY MURDER

LESLIE MEIER

KENSINGTON BOOKS

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Books by Leslie Meier

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Copyright Page

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Copyright Page

For Anne Toole

Chapter One

L

ucy Stone shut her eyes tight and rolled over, trying to ignore the ringing phone on her bedside table. When that didn’t work, she wrapped a pillow over her ears and held it tight, but the ringing continued. She knew who was calling, and it was beginning to be a nuisance, these phone calls at five and six in the morning. Sighing, she glanced at the clock, which read 6:30, noting a small improvement in timing. She picked up the handset and pressed it to her ear, bracing for the coming verbal onslaught.

ucy Stone shut her eyes tight and rolled over, trying to ignore the ringing phone on her bedside table. When that didn’t work, she wrapped a pillow over her ears and held it tight, but the ringing continued. She knew who was calling, and it was beginning to be a nuisance, these phone calls at five and six in the morning. Sighing, she glanced at the clock, which read 6:30, noting a small improvement in timing. She picked up the handset and pressed it to her ear, bracing for the coming verbal onslaught.

“Mom! It rang and rang. I thought you’d never answer. I thought something had happened. . . .”

If only,

thought Lucy, imagining herself someplace far away. A desert island, perhaps. “No. I’m fine. I’m right here, in bed. You woke me up.”

thought Lucy, imagining herself someplace far away. A desert island, perhaps. “No. I’m fine. I’m right here, in bed. You woke me up.”

“I’m sorry. I can’t get the hang of this time difference. France doesn’t switch to daylight savings for a couple more weeks. . . .”

Lucy wasn’t up to making complicated time zone calculations, but she knew the clock had sprung forward last week. “It’s six thirty here, in the morning, and I was asleep.”

“I’ll try to remember . . . but it’s just . . . well, I . . . I . . .”

Lucy gritted her teeth, wishing she could avoid hearing the sobs of her oldest daughter, Elizabeth. “There, there,” she murmured. “It’s not so bad. . . .”

“It is! It’s h-o-o-orrible!” exclaimed Elizabeth, her voice wobbling through her sobs. “I ha-a-ate Paris!”

Despite her affection for her oldest daughter, Lucy was finding it hard to sympathize with her constant complaints about her new situation. After working in Palm Beach for the luxurious Cavendish Hotel chain, Elizabeth had recently been promoted to assistant concierge in the Paris hotel. To Lucy, it seemed like a fantastic opportunity, especially since she herself had always dreamed of going to Paris but had never managed to make the trip.

“I know change is never easy,” admitted Lucy, in a consoling tone.

“Everything they say about the French is true,” declared Elizabeth. “They’re rude and bossy, and they talk too fast, and when you ask them politely to ‘

Répétez, s’il vous plaît,

’ they give you a condescending little smile and switch to English. How am I supposed to improve my French if they always speak to me in English, huh?”

Répétez, s’il vous plaît,

’ they give you a condescending little smile and switch to English. How am I supposed to improve my French if they always speak to me in English, huh?”

“They probably think they’re being helpful,” said Lucy.

“No, that’s the last thing on their minds. They’re putting me down. That’s what they’re doing.”

“It’s easy to feel a bit paranoid when you don’t quite understand what people are saying,” suggested Lucy.

“Paranoia? Is that what you think? That I’m paranoid?” She paused. “You know what they say about paranoia. You’re not paranoid when they’re really out to get you.”

“Who’s out to get you?” asked Lucy.

“They all are, especially my coworkers. I know they’re just aching to get rid of me and take my job, they don’t think I deserve it.”

“Maybe you’re the one who doesn’t think she deserves it,” said Lucy, hastening to add, “But you do. You did a super job in Palm Beach.”

“That’s yesterday’s news,” muttered Elizabeth. “Nobody here knows, or cares, about Palm Beach.” She sighed. “I really miss my cute little apartment with all my nice stuff.”

Lucy was busy listening between the lines, suspecting Elizabeth didn’t actually miss her West Palm Beach apartment all that much but did miss her boyfriend, Chris Kennedy. Elizabeth hadn’t been talking about Chris much lately, and Lucy suspected the relationship hadn’t survived the long-distance separation.

“The place I’ve got here is tiny and grotty,” continued Elizabeth, “and I really do have the roommate from hell. Sylvie has taken the bedroom all for herself, and I have to sleep on a fusty old futon. I think I’m allergic to it. And she smokes!”

“It’s a big adjustment, but you’ll manage,” said Lucy, yawning and thinking longingly of her morning cup of coffee. “And you’ll be a better, stronger person for rising to the challenge.”

“Mom, that doesn’t sound like you,” said Elizabeth, finally lightening up. “What have you been smoking?”

“Nothing,” insisted Lucy, “nothing at all. But I did watch Norah on TV yesterday. She had one of those motivational people on. ‘If you dream it, you can do it.’ ”

“It’s not that easy,” said Elizabeth. “Sometimes your dreams turn into nightmares. Or

cauchemars.

That’s what the French call them.”

cauchemars.

That’s what the French call them.”

Lucy found herself smiling, satisfied that once again she’d talked her daughter off the ledge. “Hang in there, sweetie. Mommy loves you. And Daddy, too.”

“I know,” replied Elizabeth. “Thanks for listening.”

“Anytime,” said Lucy. “But preferably after lunch. Call me after you’ve had lunch. I should just about be finishing my shower then.”

“I promise, Mom. Bye.”

Lucy replaced the handset in its holder and flipped back the covers, getting out of bed. Winter tended to linger well into spring in the coastal Maine town of Tinker’s Cove, and it was chilly in the upstairs bedroom on this mid-March morning, so she quickly put on her robe and slippers and hurried downstairs to join her husband, Bill, in the toasty warm, bacon-scented kitchen.

Bill was a much-sought-after restoration carpenter who fixed up vacation homes for old-time Yankee families from Boston and Wall Street hotshots. He was already dressed for the day in a plaid flannel shirt, jeans, and work boots. His still sported a healthy head of hair and a full beard, but the brown was now mixed with gray. “Elizabeth again?” he asked, filling a mug with coffee and handing it to her.

Lucy cradled the mug in both hands and took the first, life-giving sip. “Yes. She hates everything in Paris—the people, her roommate, her job.”

The toaster popped, and Bill buttered a couple of pieces of toast, arranged them on a plate, and added the eggs and bacon he’d been frying. He sat down at the table and took a bite of bacon. “An improvement,” he said philosophically. “Yesterday it was the entire country, all forty million Frenchmen, or however many there are now.”

Lucy joined him at the table. “You are an optimist,” she said with a sigh. “I’m disappointed in Elizabeth. I really am. This is a wonderful opportunity, and I don’t think she’s taking advantage of it.” She paused, taking another sip of coffee. “You know, I took French in high school. I bet I could get along just fine in Paris.”

That thought remained in Lucy’s mind as she got herself ready for the day and saw her two younger daughters, who were still living at home, off to school. Zoe usually caught a ride with her friend Renée, shunning the school bus now that she was a junior at Tinker’s Cove High School. Sara drove herself to nearby Winchester College in an aged, secondhand Civic. Lucy’s oldest child and only son, Toby, lived on nearby Prudence Path with his wife, Molly, and their just-turned-four-year-old son, Patrick.

Since it was Thursday Lucy didn’t have to get to work early; the deadline for the

Pennysaver

newspaper, where she was a part-time reporter and feature writer, was noon Wednesday, and the paper came out on Thursday, giving the staff of three a brief reprieve before they started work on the next week’s edition. For years now she’d met three longtime friends for breakfast on Thursday mornings at Jake’s Donut Shack; they all considered this weekly get-together a top priority.

Pennysaver

newspaper, where she was a part-time reporter and feature writer, was noon Wednesday, and the paper came out on Thursday, giving the staff of three a brief reprieve before they started work on the next week’s edition. For years now she’d met three longtime friends for breakfast on Thursday mornings at Jake’s Donut Shack; they all considered this weekly get-together a top priority.

This morning she was eager to share her anxiety about Elizabeth with the group and get their input, as they were all mothers and had plenty of experience guiding their children through young adulthood. When Lucy arrived, she found Rachel Goodman and Pam Stillings already seated at their usual table. She gave a wave to Norine, the waitress, and joined them.

“Another phone call,” she began as Norine set a mug of coffee in front of her. “At six thirty this morning. Elizabeth is driving me crazy.”

“She’s all alone in a strange country,” said Rachel, who was a psych major in college and had never gotten over it. “She feels alienated,” she said, twisting a lock of long, dark hair. “She needs lots of support.”

Lucy took a swallow of coffee, then shook her head. “I can’t believe she’s not rising to the occasion. I mean, what I wouldn’t give to be in her shoes.”

“I know,” agreed Pam Stillings, who was married to Lucy’s boss at the

Pennysaver,

Ted Stillings. “Imagine being young and beautiful and in Paris!” Pam was a free spirit; she still clipped her hair into a ponytail and often wore the poncho she’d picked up during her junior year in Mexico.

Pennysaver,

Ted Stillings. “Imagine being young and beautiful and in Paris!” Pam was a free spirit; she still clipped her hair into a ponytail and often wore the poncho she’d picked up during her junior year in Mexico.

“It’s not that simple,” insisted Rachel, adjusting the horn-rimmed glasses that covered her huge brown eyes. “Life isn’t like perfume ads. Elizabeth is in a completely foreign culture. They even speak a different language. It’s no wonder she’s struggling to find her footing.”

“I guess so,” grumbled Lucy, looking up as Sue Finch arrived.

Sue was the glamorous member of the group, and this morning was no exception. Her glossy black hair was styled in a flawless pageboy, and she was wearing skinny black jeans and a bright color-blocked tunic. “What do you guess?” she asked, slipping into her seat.

“That it’s entirely normal for Elizabeth to be miserable in Paris,” answered Lucy.

“

C’est dommage,

” cooed Sue, adding a translation for the others. “It’s too bad. I love Paris. I love everything about Paris. . . .” She curved her scarlet lips into a smile, seeing Norine approaching with a coffeepot. “Except the coffee cups are too small and everyone smokes.”

C’est dommage,

” cooed Sue, adding a translation for the others. “It’s too bad. I love Paris. I love everything about Paris. . . .” She curved her scarlet lips into a smile, seeing Norine approaching with a coffeepot. “Except the coffee cups are too small and everyone smokes.”

“Regulars for everyone?” asked Norine. Receiving nods all round, she left the pot on the table and trotted off, scribbling on her order pad.

“That’s one of Elizabeth’s major complaints,” said Lucy, picking up the conversation. “She says her roommate smokes all the time and stinks up their apartment, which is tiny.”

“I can’t seem to work up much sympathy,” said Sue.

“You are hard-hearted,” teased Pam as Norine arrived with a sunshine muffin for Rachel, yogurt topped with granola for Pam, and hash and eggs for Lucy. Sue never had anything more than black coffee and lots of it.

“No, I’m not,” insisted Sue. “In fact, I have some amazing news. Norah is doing a show about women who make a difference. . . .”

They all knew that Sue’s daughter, Sidra, was a producer for Norah Hemmings’s Emmy-winning daytime TV show. “And you’re one of those women?” asked Lucy, jumping to a conclusion.

“No. At least I don’t think so. But Sidra says Norah wants to tape the show right here in Tinker’s Cove.”

“Here? Why here?” asked Rachel.

“Sidra says she thinks it’s because Norah has that fabulous vacation house here and she’s exhausted and wants a bit of a break. So she’s going to tape the last show of the season here, and then she’s going to turn off the phone and lock herself in her twenty-two-room mansion by the sea for a period of silent rest and recuperation.”

“She’s got millions of dollars and dozens of assistants who do everything for her, including walking the dog and running her bath. How can she be exhausted?” asked Pam.

“It’s the constant pressure to perform. I’m sure it’s terribly stressful,” said Rachel. “She needs time and space to get in touch with her authentic self.”

“Just turning off the phone sounds wonderful,” said Lucy. “With twenty-two rooms, do you think she’d have one little room for me?”

“I doubt it,” said Sue, grinning wickedly. “But Sidra says we can all have free tickets to the taping.”

“Aren’t they always free?” asked Pam.

“Don’t quibble,” admonished Sue. “Just think, you get to see the show live without having the expense and trouble of traveling to New York.”

“Wow,” Pam said cynically. “Can’t wait.”

As it happened, Pam didn’t have long to wait. In a matter of days a crew of workmen arrived and began constructing a temporary enclosure on the Queen Victoria Inn’s spacious outside deck overlooking the cove. A stage with a seating area for guests was placed in front of large glass windows that provided a fabulous view of pine trees and a scattering of houses with steeply pitched roofs, and a glimpse of the harbor, where a few boats bobbed in the choppy waves, newly freed from the ice, which had melted only a few weeks ago. Heavy-duty power lines were installed for cameras and lights, and propane heaters and theater seats were added for the comfort of the audience.

Lucy covered the entire process for the

Pennysaver,

which got only a few letters demanding to know why Norah hadn’t used local workmen instead of sending her own crew of carpenters. Most Tinker’s Cove residents were caught up in the excitement, eagerly awaiting the glamorous TV star’s arrival and looking forward to seeing the show live in their very own hometown. The free tickets quickly became a hot commodity, and those lucky enough to hold them got cash offers from people who wanted to see the show, but few gave in to the temptation to sell, refusing even fifty and a hundred dollars per ticket.

Pennysaver,

which got only a few letters demanding to know why Norah hadn’t used local workmen instead of sending her own crew of carpenters. Most Tinker’s Cove residents were caught up in the excitement, eagerly awaiting the glamorous TV star’s arrival and looking forward to seeing the show live in their very own hometown. The free tickets quickly became a hot commodity, and those lucky enough to hold them got cash offers from people who wanted to see the show, but few gave in to the temptation to sell, refusing even fifty and a hundred dollars per ticket.

When the big day finally came, Lucy and her friends were seated in the very first row.

“It pays to have connections,” said Sue. “I’m sure Sidra got these seats for us.”

She pointed to her daughter, who was holding a clipboard and conferring with a lighting technician. Tall and New York City thin, she looked terribly professional in tailored black slacks, a gray cashmere sweater topped with a chunky necklace, and leopard-print ballerina flats.

“The lighting is always beautiful on the Norah show,” said Rachel. “I don’t know how they do it, but the people in Norah’s audience always look terrific.”

“Norah always looks amazing,” said Lucy. “She’s no spring chicken, that’s for sure.”

“I bet she’s had plastic surgery,” snorted Pam. “It’s easy to look good when you can afford face-lifts and facials and professional makeup.”

“I think it’s the hair,” said Sue. “When your hair looks good, you look younger. Frizz makes you look older.”

“Really?” asked Lucy, who was suddenly painfully aware that she hadn’t bothered to style her hair that morning but had given it only a good brushing.

Other books

The Fighting Man (1993) by Seymour, Gerald

The Laughter of Strangers by Michael J Seidlinger

Fan the Flames by Rochelle, Marie

Hold Your Breath 02 - Unmasking the Marquess by K.J. Jackson

All of me by S Michaels

Designer Genes by Diamond, Jacqueline

Dorothy Eden by Lady of Mallow

Something Like Redemption (Something Like Normal #2) by Monica James