Fusiliers (15 page)

Jeffrey Grimes, who had fought at Lexington as a corporal, had by late 1775 been promoted to serjeant, after a service of just five years in the army. To the knot on his shoulder, the serjeant added a sash, coloured scarlet with a stripe of royal blue to tie around his midriff. Grimes was moving up the ranks swiftly for the serjeant’s duties were considered onerous.

‘A serjeant should … be able to instruct’, one expert opined, ‘and he will not only be required to inform his inferiors alone but sometimes his superiors likewise. He must understand writing and accounts and must be well informed in the whole

routine

of the service and customs of the army.’ Another military savant believed it was essential for such non-commissioned officers to display ‘honesty, sobriety, and a remarkable attention to every point of duty’.

The burden on serjeants during those weeks on Staten Island was certainly great. Daily, they schooled the new recruits and drafts, getting them to fit into their company, answering words of command as it wheeled about the fields. In many such groups of the 23rd there was only a single lieutenant with any idea of his business, the captains being elsewhere and the 2nd Lieutenants as green as the men.

Those serjeants or corporals who failed to maintain the standards required of them could be broken by regimental court martial. In contrast with the more serious general court martial, this was called for misdemeanours such as spitting, slovenliness or drunkenness. A man would be judged by his own corps, and the proceedings, often held in a tent in the field, dealt with the business in a matter of minutes. They would face the ignominy of having the knot ceremonially cut from their shoulder in front of the regiment, being reduced to the rank of private. It had happened to enough men in the 23rd and it was certainly regarded as a humiliation. It did not happen to Serjeant Grimes.

Throughout July and the early part of August, the regiment bivouacked on the island, living under canvas and marching about between the prosperous farms and orchards. By day there was drill

and marching. At night the aroma of cedar and sassafras drifted into the tents.

While the companies went about their business, the regiment itself was almost bereft of leadership. Lieutenant Colonel Bernard had never fully recovered from being shot in the thigh the previous year. He occasionally presented himself for duty, but languished at other times for weeks on his sick bed. One friend of Bernard’s noted months previously that ‘he is confined and not likely to get better’ and upon asking why the colonel did not join all the other wounded officers going home, the old gentleman opined he did ‘not think he would be better there than here’.

It may be that Bernard stayed because he hoped for some promotion, or that he wanted to keep a fatherly eye on his boy, who still did duty as a lieutenant in the regiment. Disaster struck in early August though. Benjamin Bernard the younger was laid low on Staten Island by one of those ‘camp fevers’ that afflicted armies under canvas, and by the 12th had died aged just twenty-two. In such difficult times, the regimental major should have been on hand to command, but Blunt had sold the majority to William Blakeney the previous year and that Irishman chose to remain in England. Blakeney was opposed to the war and, having taken a wound at Bunker Hill, was not going to expose himself to the dangers of another campaign. Instead he resorted to ever more fanciful flights of imagination to explain his refusal to return to the 23rd. This unsatisfactory situation left the regiment under the superintendence of an unsatisfactory officer, that boozy Scot Grey Grove.

There can be little doubt that this combination of Captain Grove’s taking charge with Lieutenant Colonel Bernard appearing occasionally from his sick bed would have been felt by all ranks. ‘The state of the regiment in every military point of view’, noted one serjeant of the Royal Welch, ‘depends on the exertion and vigilance of the officer commanding.’ In one aspect though they were fortunate, for the strokes being planned by General Howe involved warfare on a huge scale, and the 23rd would at least be ably supported in the battle that was about to come.

In his headquarters, the British commander-in-chief eyed the prize of New York like some rare flower surrounded by beds of thorns. Staten was just one of several outlying islands that separated America’s principal trading post from the open sea. The long British build-up had

allowed George Washington plenty of time to lay out defences. Cannon were sited on the harbour, denying the Howe brothers any chance of sailing straight up to land their men at the city quays. The approach would have to be indirect, overland, so there were lines on Long Island. Where that land came close to Manhattan at Brooklyn, redoubts had been thrown up to guard the most obvious landward route towards the city. Other forts guarded likely landing places or strong ground both above the city of New York and on the Jersey shore.

Washington was certainly outnumbered, having something like 19,000 men at his disposal, and his predicament was made all the more awkward by the dispersal of troops necessary to cover various possible landing places. He would require immediate word of any British move and excellent staff work to get his men to the threatened sector. His only real advantage lay in occupying a central position from which he might quickly move reserves to where they were needed.

General Howe, though, would have an army at his disposal large enough to stage multiple landings or outflank his enemy. So large was it, the brigades formed in Halifax were grouped together into divisions. The Hessians formed one (with a second on its way at sea), and Earl Charles Cornwallis, a general of undoubted gifts and zeal, was given the plum job of commanding the

corps d’élite

containing the grenadiers and light infantry. Generals Percy and Clinton were also available to lead divisions, but their chief had other ideas. Indeed Howe would keep all of the respected senior officers in the army close to himself, commanding elite forces in the coming battle.

Those who led the brigades made up of marching regiments of foot were of a lower quality altogether. Major General Robertson, at the head of the 1st Brigade, was already acquiring a reputation for corruption on a grand scale. Pigot, who had the 2nd, was competent but uninspired and had at least survived his baptism of fire at Bunker Hill. It was, however, the commander of the 4th Brigade, James Grant, who was destined to lead a division in which the 23rd would be employed.

Grant was, depending upon one’s perspective, a canny political operator and generous host or a braying buffoon with little idea of generalship. During the siege of Boston, he had given lavish parties, sustaining many an impoverished officer. Grant himself had grown fat and gouty from overindulgence, savouring the delicacies prepared by Baptiste, his black cook, who accompanied him on campaign. As a

veteran of the Seven Years War in America and former governor of Florida he also knew the colonial political scene.

Although Grant’s letters revealed a sharp mind, he succumbed easily to hubris and had moments of dreadful judgement. As a Member of Parliament he had made a notorious speech early in 1775 in which he predicted the Americans ‘would never dare to face an English army’, and that he would be able to march from one end of the continent to the other with 5,000 men. These public utterances were surpassed by blistering private rhetoric, Grant writing to one correspondent as the New York campaign began that ‘if a good bleeding can bring those Bible-faced Yankees to their senses – the fever of Independence should soon abate’.

Officers who considered themselves more sane on the subject of dealing with the rebellion bemoaned Grant’s influence over General Howe. Earl Percy noted tartly, ‘Brigadier General Grant directs our Commander-in-chief in all his operations. Mr Howe is I believe the only man in his army who does not perceive it.’ Percy and others thought Grant and one or two other influential Scots such as Captain Nisbet Balfour, one of Howe’s aides-de-camp, pushed their chief to take brutal measures against the Americans. Certainly it was clear by mid-August, with 350 ships and tens of thousands of men, that the tables had been turned since the march to Lexington, and that General Howe was ready to bring overwhelming force to bear on the rebellion.

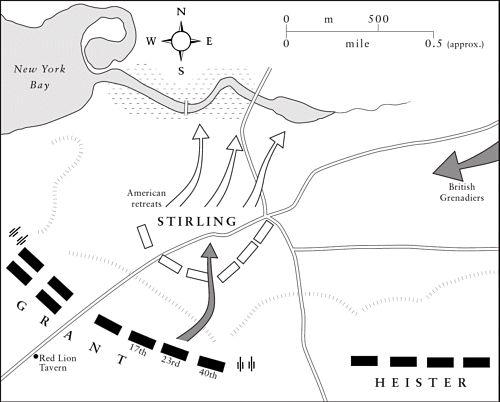

For Major General William Alexander the first real intimation of battle came when he was roused at 3 a.m. on 27 August. Alexander, or Lord Stirling as his men called him, since he had claimed right to an old Scottish earldom, had been placed in charge of the American right at Long Island. Five days earlier, the British had moved over from Staten Island using seventy-five specially built flat-bottomed boats. It was a textbook operation in which 15,000 soldiers were ferried across in a day.

Trouble then was expected, as Alexander issued orders to his battalions and went forward to see what was going on. There was only a faint glimmer of light on the eastern horizon, over to his left, as he met Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Attlee, in command of the Pennsylvania Musket Battalion, a light infantry corps that furnished his outposts. There had already been some scattered firing as British scouts ran into Attlee’s outlying men. Alexander and Attlee conferred atop Gowanus Ridge, the feature forming the main American

defensive position on Long Island. It was ground well suited for defence, having the advantage of height, with sea anchoring Alexander’s right flank at Gowanus Bay and a thick wood giving some security to his left. The only drawback to this fighting ground was that the bay curved around behind some of it, and a swamp extended a little inland, making it hard for the general’s men, particularly on his right, to get away quickly if they had to.

The disposition of the

23

rd at Long Island

General Alexander was no defeatist however – far from it. He had called up his regiments from their bivouacs and would soon have them deployed. Before the general had finished conferring with the commander of his outposts, he spotted the first redcoats through the murk of the early summer morning, less than half a mile ahead, near the Red Lion Tavern.

A road ran down Alexander’s sector of Gowanus Ridge, towards the enemy, and as his troops marched up he directed Attlee to fall back to the left of the road, and re-form in the woods, while his two best regiments, from Delaware and Maryland, got into position, forming a

line ready to receive their enemy. At this point, dawn, Alexander’s forces in place topped 1,000. Far more redcoats could be seen in front of them, but the American commander could at least reckon on having the best men in the American battle line.

The ‘Delaware Blues’ were so nicknamed because they were virtually the only American regiment in the battle that were smartly uniformed in blue coats with red cuffs and lapels, as well as domed leather caps shaped a little like those of the Hessian fusiliers. The Maryland soldiers, noted as ‘men of honour, family and fortune’, wore an item more widespread on the lines that morning, a fringed hunting shirt. These garments were usually made of linen, often in its natural colour, sometimes dyed in some suitable forest colour. Washington had ordered these to be the uniform of the Continental Army, a move that was both practical, given the wide availability of such garments, and from a desire to play on redcoat fears, born of the previous year’s events in Boston, of American sharpshooters. ‘It is a dress’, wrote Washington, ‘justly supposed to carry no small terror to the enemy, who thinks every such person a complete marksman.’

Approaching these Americans were General Grant’s division, 2,650 men in nine regiments. Grant deployed his men into battle formation. On his left, he went for compactness, grouping four of them, two behind two. To the right, Grant extended his formation, pushing four battalions out in line, one next to the other. The 23rd were in this area, finding the 17th to their left and 40th to their right. Two pieces of field artillery were also unlimbered to the Fusiliers’ right (and another pair, far off to the left close to Gowanus Bay). One regiment was held in reserve, guarding the baggage. Grant’s cannon began to fire about 5 a.m., and the first hours of the battle consisted of bombardment and clashes of musketry where the British tried to explore or push into the American position.

Grant’s men probed first on the American right, then on its left. It was during these latter movements that the 23rd and 40th took position on a knoll close to the extreme inland point on Alexander’s line. That general’s troops meanwhile took great satisfaction from the results of these contests. Attlee, leading a mixed force of his own battalion with some Delawares and riflemen, went to contest the knoll to his front left. Initially his troops were staggered by the fire they received, but soon damned the British for their poor marksmanship and pushed on. ‘The enemy’, Attlee reported by letter, ‘fled with

precipitation, leaving behind them twelve killed upon the spot.’

Alexander’s men became exultant. The Delawares, Marylanders and other detachments that had joined them were standing in open battle against professional soldiers. Colours flying, they were enduring the enemy bombardment like veterans, and holding at bay a force several times their number. This happy reverie was broken at 9 a.m. when two distinct thumps of a heavy cannon were heard. What could it mean?