Fusiliers (46 page)

When Greene suffered a defeat near Charleston several weeks after Colonel Hayne’s death, Major Frederick Mackenzie marvelled at that general’s perseverance: ‘The more he is beaten, the farther he advances in the end. He has been indefatigable in collecting troops, and leading them to be defeated.’ That Fusilier officer had understood a vital truth as six years of war for America neared their climax: the enemy could withstand any number of drubbings, whereas Britain’s resolve to carry on would crumble in the face of one more major setback.

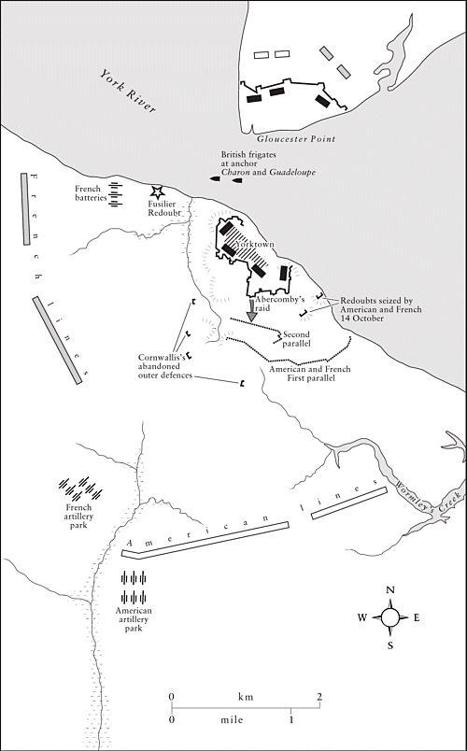

The troop dispositions at Yorktown

TWENTY-ONE

When Serjeant Lamb Shunned American Hospitality Once More

The French infantry’s white uniforms made them eminently visible at night, so, on the evening of 30 September, some Fusiliers posted as pickets in front of their redoubt, to the west of town, easily spotted their enemy through the murk, coming through the trees. There was a brief exchange of musketry, and the redcoat lookouts took to their heels.

The French troops pushed on up a wooded slope to open, flat ground in front of the Fusiliers’ Redoubt. Inside the work, its defenders, roused by the exchange of musketry, leapt to their firing positions. There were about 130 Fusiliers, thirty marines and some gunners who manned two 12-pounder cannon and some small mortars called coehorns. Serjeant Lamb, like many of the men in that small fort, was sick, but had not yet weakened to the point that he had been carried off to one of the many houses being used as makeshift hospitals. Captain Peter had gone down with fever, so the redoubt was under the command of Captain Apthorpe, the New Englander – and the only Fusilier officer still serving with the regiment at Yorktown who had been present at that St David’s Day dinner in Boston six and a half years previously.

The defenders waited until the French had trotted to just a few dozen yards from the redoubt before opening fire. Their assailants beat a rapid retreat across the open ground.

When morning came there were unmistakable signs of the French establishing works just 450 paces to the front of the Fusiliers’ Redoubt.

Elsewhere, at the town’s southern defences, the pick-and-shovel work began in earnest too, Earl Cornwallis having given up two redoubts which he felt were too exposed to be defended. Conceding these outlying posts caused much muttering in the British camp, and one French officer noted, ‘This … gave us the greatest possible advantage.’ The move against the Fusiliers’ Redoubt on 30 September may have been no more than a reconnaissance in force to see whether it too had been abandoned.

Certainly, the small fort on a cliff overlooking the York River would have been quite a prize for the French. If they could capture it, thus controlling the ridge upon which it stood, they would be able to fire their cannon into the heart of Yorktown, on lower ground to the rear of the redoubt. The game would be up if that happened. The place defended by the Fusiliers, though, was quite strong – a ditch 6 feet deep had been dug in front, its ramparts rose 6 feet above ground level, and sharpened tree trunks had been driven into the ground to thwart anybody climbing the steep walls. Inside this little world, just a hundred feet across, was the sheltered interior with its gun platforms, and firing steps. At quiet times, Fusiliers dozed on their blankets or used small fires to cook. When the alarm was sounded they would grab their muskets and step up to the firing positions.

On the morning of 1 October there was a sense in both camps that the siege was getting under way in earnest. French officers superintended the unloading of their heavy guns at a landing point on the James River six miles to the south. Once these 24-pounders and heavy mortars were in place, the real smashing of Cornwallis’s defences could begin. The Allies divided their line, as they sunk their first parallel, Americans on the right or east, French on the left or south and west. Across the water, at Gloucester, a combined Franco-American force also began its investment. In all the two nations would commit 20,000 troops to the land battle (about 9,000 of them French), while Cornwallis’s army of about 7,500 was swollen by about 2,000 men as sailors and others disembarked to join the defence.

In Yorktown itself, the selection of hungry mouths, that ruthless expedient necessary to withstand a siege, had begun. By orders the previous day, all horses except those belonging to the cavalry were to be turned over to the quartermaster general. The lame or sick animals were quickly killed on the beach, some being shot or bled to death, others led out into the surf and drowned by their drivers. It would not

be long before the eyes of those directing the defence would fix upon the hundreds of negroes crammed into the town.

As the sick multiplied, medicines began to run out. ‘We have already resorted to using earth mixed with sugar to deceive the poor invalids, which is used as an emetic,’ wrote Captain Ewald. ‘When they are bled, the blood of everyone is vermilion, and it does not take long before the land fever turns into putrid fever.’ Officers did not fare particularly well, with Ewald himself resorting to ‘the most dreadful remedy in the world’, mixing his rum with China powder – the composition of which is uncertain, but it was probably an opiate.

With the siege lines opened, firing into the town began in earnest. American sharpshooters used their long rifles to pick off British gunners or sentries. Field guns were used to annoy one another’s forward positions – but the real bombardment would only start when the French assembled the heavy artillery being brought across the peninsula. There were some skirmishes too, particularly on the Gloucester side, where Charles Mair, an officer serving with the 23rd’s light company, reinforcing Tarleton, was killed on 3 October.

Three days later, just after dark, the French decided to push their advance once more against Apthorpe’s redoubt. This time they were trying to construct a battery, a little forward of their trench, in order to receive the heavy guns. The working party, which consisted of members of the Touraine infantry and Auxonne artillery regiments was met with a hail of fire. ‘A rocket rose from the redoubt at once,’ wrote a German officer in the British lines, ‘whereupon the cannon fire from all our positions in the line began and continued throughout the night.’ Six of the Touraine regiment’s grenadiers were hurt, as were two artillerymen, one, a young officer, having his leg shot off, later dying from his wounds.

The contest between Apthorpe and the regiments in front of him went on much as the wider struggle, a battle of wits between gunners and engineers as they jockeyed for the best firing points, offering the angles and ranges that would allow them to start blowing holes in Yorktown’s earthworks. Unfortunately for the British, the French were much better at this technical business, which meant day by day they advanced their plans despite the defenders’ best efforts. Apthorpe’s battery could fire 12-pound shot or coehorn shells, exploding grenades the size of pineapples, into the battery being built in front of him. Once the French filled their gabions, big wickerwork baskets full of

stones and soil, piling up earth on the enemy side of them, the 12-pound balls had little effect. The coehorn shells shot high into the air over such obstacles, but getting them to fall exactly where the French were working was a tricky feat of marksmanship.

Lieutenant Louis de Clermont-Crevecoeur of the Auxonne Regiment was directing the working parties under fire from the Fusiliers’ Redoubt that night of the 6th. A keen officer from an impoverished aristocratic line of Lorraine, he lamented the fatal wounding of his brother officer, but noted phlegmatically, ‘The English gave us quite a pounding but did us little harm.’ As his men consolidated their earthen walls, they became safer still, and the lieutenant found that one of his principal problems was digging in soil so full of tree roots.

The men of Auxonne and Touraine toiled away day after day building platforms for their guns: four 12-pounders, two 24-pounders, six howitzers and one heavy mortar. This was the battery that opposed the two 12-pounders and coehorns in the Fusilier Redoubt. It is true that Clermont-Crevecoeur’s mission was to hit the frigates in the York River just to his left, as well as batter the redoubt, but the imbalance in firepower will give some idea of the situation that the Fusiliers in particular, or British defenders in general, found themselves in.

Clermont-Crevecoeur had spent three of his twenty-nine years at the Metz artillery school, widely admired as the world’s finest academy of its kind. Apthorpe, that loyalist Yankee, by contrast possessed plenty of tactical sense about how to handle infantry, developed in countless affairs or skirmishes, but he was no master of field engineering. What he could give his men was dauntless leadership under fire. But what value were heroics in the face of science? The French lieutenant knew that he would soon be bringing a vastly greater weight of shot to bear on the redoubt in front of him than it could possibly return. Its defeat would simply be a matter of time.

At headquarters in New York, unwelcome reports from Virginia had been received in tandem with those of the naval gentlemen filing in from the dockyards. A fleet under that plodder, Admiral Graves, that had been roughly handled off the Virginia Capes early in September had returned to New York to repair and refit. Major Frederick Mackenzie observed the comings and goings at headquarters, growing steadily more angry. He knew that the fate of far more than his regiment was at stake, writing, ‘We are certainly now at the most

critical period of the war.’ As a veteran of the defence of Newport in Rhode Island three years earlier, Mackenzie knew that decisive action could still turn the situation to Britain’s favour

Faced with looming crisis, Clinton held meetings. Boards of generals decided that something must be done to relieve Cornwallis. Mackenzie had managed to rub along with his querulous commander-in-chief by working diligently and keeping certain opinions to himself. Privately, he was cynical about how far Clinton really wanted to extract Cornwallis from his predicament, believing that ‘should [Clinton] remain … without undertaking something, he will be blamed by everyone, let the matter end as it may; and it will be said that he remained an unconcerned spectator of the fate of that Army’.

Henry Clinton made his decisions in committee so that responsibility could be shared. As one meeting of grave-faced officers followed another, he started to insist that everything would depend on the navy. Troops who had been embarked for a cherished scheme of Clinton’s to attack Rhode Island were given new orders to be in readiness to sail south.

When could they set off? An initial estimate of 5 October was given. On 28 September Admiral Graves, however, told the commander-inchief that this must be revised to 8 October. Just two days later, the admiral opined that 12 October might be more a manageable departure date. As one excuse about hemp, cordage or yards followed another, relations between the services became strained. ‘If the Navy are not a little more active,’ Mackenzie observed bitterly, ‘then it will be too late. They do not seem to be hearty in their business or to think that the Army is an object of such material consequence.’

On 6 October, the same day that Lieutenant Clermont-Crevecoeur threw up his battery opposite the Fusiliers’ Redoubt, Major Charles Cochrane, one of Cornwallis’s ADCs who had come to New York, was sent back with a message for his master. Cochrane would take the risky passage south in a vessel so small that it might run the French blockade of the Virginia capes without arousing suspicion. He was carrying dispatches from the commander-in-chief, telling Lieutenant General Cornwallis what might be done to save his army.

The Fusiliers in the redoubt received their rude awakening around 3 p.m. on 9 October. The great battery in front opened up for the first time, not on them but at the

Guadeloupe

, a Royal Navy frigate

anchored a few hundred yards to their right and rear. The army’s optimists had been asserting for weeks that the French had no siege guns, but soon enough those who peered over the parapet of their redoubt watched the

Guadeloupe

getting peppered by big-hitting cannon.