Fusiliers (54 page)

Despite the urgency of this public advocacy or the Deputy Adjutant General’s private entreaties it would take years for the formation of proper light infantry corps and the ‘revision’ of Dundas’s old regulations to the point that they became a dead letter. During the time the Duke of York occupied himself with myriad schemes for improving the efficiency of the army. Military education was to be put on a proper footing, recruiting standards raised and the soldier’s lot improved. The climate for this work improved immeasurably as the threat of French invasion produced a national consensus about strengthening the army. The old partisanship of Whig and Tory began to wither. With greater unity in Parliament, York was able to carry his reforms into sensitive areas such as preventing abuses of the commissions system, for many of the maladies that Horse Guards sought

to treat (such as commissioning boys or allowing them promotion without any military experience) were ploys favoured by wealthy landowners to buy their sons status.

Fear of Bonaparte’s legions was to have a more powerful effect on the landowners than their desire to protect their army privileges. However the yeoman Briton’s dread of social upheaval following the French revolution would also see some of the more benign or enlightened customs of the eighteenth-century army swept away. It became far harder to obtain a commission from the ranks, as those sterling serjeants of the 23rd, Richard Baily, William Robinson (killed at Guilford) and George Watson, had done. As the wars against France progressed, it even became unofficial policy to post such men away from the regiments where they had hitherto served, lest their elevation to a gentleman’s rank cause too much embarrassment for all concerned. The application of the lash or capital punishment also become more systematic as the officer class sought to crush any unrest.

In the mid-1790s Britain sized up the French revolutionaries and decided it despised them. During the late 1790s, Calvert and the others who ran the army from Horse Guards were engaged in a dizzying wave of reforms necessary to raise the redcoat’s game so that it could confront them.

Early in 1799, Calvert was made Adjutant General of the army. In June of the same year he married Caroline Hammersley – a love match, albeit to a banker’s daughter, and a family connection that would eventually allow Calvert’s first-born to inherit a baronetcy. His social credentials had been vouchsafed at last. With Calvert matured into a man of substance in the world of army politics, the boy whom Fusiliers spotted disembarking in New York two decades before was quite different in appearance. Frequent attendance at the Duke of York’s lavsh table had helped him pile on pounds, his complexion was often florid and the recession of his hairline, something that had begun in his twenties, left him with a bald pate. Calvert’s bright eyes, though, still radiated their strong intelligence, and his manner reinforced the impression. Not long after his appointment to the head of one of the main branches of the staff, General David Dundas was appointed to the other. Although it is clear that Calvert’s friends and mentors were doing their best to subvert Dundas’s tactical ideas, the Adjutant General maintained a professional working relationship with the older man.

As Calvert received one promotion after another from his patron he

became a valuable ally to some of the old Fusiliers he had known decades before in America. Frederick Mackenzie benefited handsomely, for the veteran of Lexington had reached an age too advanced for active soldiering. Calvert had Mackenzie appointed as secretary to the Royal Military College, the new institute of military learning created under the Duke of York’s aegis. The College, which started its work in a tavern but soon moved to more salubrious surroundings, was just one symptom of the great change brought about in the last years of the eighteenth century. A more professional army was taking shape.

It was late in 1808 when Roger Lamb finally bowed to the entreaties of his friends and family. Lamb’s meagre pay as schoolmaster had provided but a poor living to his wife and six children. If he had started his family so late in life, was it not due to his service to the Crown? And might not that beneficent Sovereign see fit to grant the former serjeant of Fusiliers a pension? Lamb’s relatives urged him to petition the commander-in-chief of Ireland, for was that not the same noble personage who owed his life to Lamb’s quick thinking at the battle of Guilford Courthouse when Serjeant Lamb had seized the bridle of the general’s horse and guided him back to British lines? The ageing schoolmaster had rejected such suggestions for many years.

In September 1808, however, Lamb finally relented. He had been reading the newspaper, when he noticed an announcement signed by ‘Harry Calvert, Adjutant General’. Lamb was by this time fifty-two and feeling the effects of his advancing years. ‘It immediately occurred to me’, Lamb reflected, ‘that this officer served in the 23rd and had always shewed himself my friend.’ The teacher’s family urged him to write immediately. Lamb petitioned the adjutant general, describing his ‘humble confidence’ that Calvert would answer his plea.

Calvert replied, recommending Lamb to the quartermaster general in Dublin. When the ageing teacher went to that man’s offices, Lamb realised that something stood in the way of his employment. The officer implied that a job could come the way of a non-Methodist, and Lamb realised that his new-found faith was objectionable to these men.

So on 7 January 1809, Lamb wrote once more to his old comrade, stating his ‘very great reluctance in giving you so much trouble’. Lamb did not mention the colonel’s attempts to stifle his Methodism, rather he asked the general in London to pass an enclosed memorial of his services to the Duke of York, in the hope that he might receive a pension.

At the time Lamb’s second letter arrived on Calvert’s desk in Horse Guards, fifteen years of hard work by the Duke of York and his staff was bearing fruit in astonishing ways. Lieutenant General Arthur Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington, had defeated the French in Portugal the previous summer. General Sir John Moore had beaten them again at the gates of Corunna, early in 1809, losing his life at the moment of victory. Regiments of riflemen and light infantry were taking to the field, outshooting and outsmarting the French tirailleurs. The Frederickian dogmas of the Prussian service, meanwhile, had crumbled with Napoleon’s smashing of their armies in 1806. The 23rd Fusiliers was destined to return from the Caribbean, sharing in the armies’ epic campaigns in the Iberian peninsula and fighting at Waterloo.

In the hour of excitement of early 1809, the Corunna expedition had no sooner landed than preparations were under way to undertake another major expedition to the Iberian peninsula. Despite the work deluging Horse Guards, General Calvert recommended Lamb’s case to the Duke of York, and fulfilled the promise he had made to that Irish serjeant in 1784 upon their return from America. On 25 January, little more than one week after receiving the former serjeant’s plea, a reply was fired off from Calvert’s office, informing Lamb that he would receive his pension.

Lamb, cannily enough, did not put his entire dependence on this patronage. He also set pen to paper, writing two memoirs of his army service that were published in 1809 and 1811. In one of these works he reflected upon his long relationship with Calvert, and noted undying gratitude for the bond created between them so many years before in the Royal Welch Fusiliers:

Attachments of persons in the army to each other terminate but with life, the friendship of the officer continues with the man who has fought under his command, to the remotest period of declining years, and the old soldier venerates the aged officer far more perhaps he did in his youthful days: it is like friendship between school-boys, which increases in manhood and ripens in old age.

The Royal Welch Fusiliers went into battle at Lexington in 1775 as a typical example of the eighteenth-century British military machine. That army quickly showed itself to be a creaky old device, an assembly of people ill-suited to the task at hand where the time-servers, boozers

or shirkers got in the way of those who were trying to do their duty. The regiment evolved through years of difficult service into a pattern for the whole army – employing novel tactics to devastating effect at Camden, while being led by zealous young officers as well as bright, motivated serjeants.

The cause on which the Fusiliers were engaged was unpopular with many at home but the army in America was inspired by men like Cornwallis to fight for is own self-respect, for the love of comrades, for pride in the red coat. In this way, it was the very effrontery of the American rebels or the malign enthusiasm of British Whigs that prompted that army to set aside ideology and evolve into a modern, professional force. It is, after all, the prosecution with honour of an unwanted war that places the hardest demands upon a soldier.

Such was the

esprit de corps

fostered by Cornwallis in particular that regiments that had stumbled in 1775 or 1776, even when outnumbering their enemy, charged headlong into the Carolina backcountry in 1781 despite knowing how badly stacked against them the odds were. Even ten years after the event, the men who could speak of this epic with the authority of veterans were a very small band indeed. Cornwallis had so few regiments of redcoats to start with – the 71st had been disbanded after the war, leaving only the 23rd, 33rd and Guards.

Had the War Office wanted to scatter this precious cadre to the winds they could not have gone about it more thoroughly: so many of the experienced rank and file were discharged during 1783–5; lots of the young officers were encouraged by the promotion system to head off to other regiments; and the tactics evolved at such cost were suppressed by Dundas and his ilk.

The knowledge of what a couple of thousand British soldiers had achieved in some far off pastures above Camden or on the hills of Guilford did not, however, die out. Cornwallis used his great authority in the army to undermine Dundas continually. Eventually that angry Scot lost the battle for the Duke of York’s ear to young Harry Calvert. It fell in the end to that man who had been taken into the Royal Welch Fusiliers as a boy, someone forged among its characters and system of fighting to recognise the precious experience he had enjoyed, and using the bitter lessons of America, to educate an army that one day would defeat Napoleon.

THE FUSILIER:

A 1776 sketch by Richard Williams showing a proposed light company uniform for the 23rd. The hat, with its Prince of Wales feathers, may be similar to that worn during the regiment’s later American campaigns.

The opening engagement of the wars in Lexington Green, where poor British troop discipline may have contributed to the outbreak of hostilities.

THE SOLDIERS:

Frederick Mackenzie in later life, when his intelligence and diligence marked him out for work at the new Royal Military College.

Thomas Saumarez was one of the longest-serving officers of the 23rd during the American war, and commanded the regiment’s captives after Yorktown.

George Baynton, painted in the mid-1780s in splendid Fusiliers dress uniform. He was one of the lieutenants selected by lot for captivity after Yorktown.

This caricature of Robert Donkin shows him as an aged general enjoying the fashionable scene at Bath. Donkin exemplified the eighteenth-century officer who knew how to play the system.

THE COMMANDERS:

Earl Cornwallis was admired by many of his officers for his aggression on the field and his desire to protect the army’s honour.

George Washington was not a great battlefield commander but a superior strategist to William Howe during the key campaigns of 1776–7.

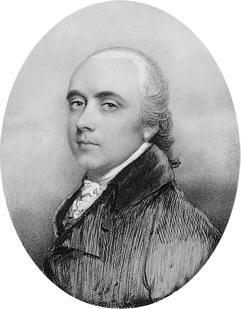

Harry Calvert (miniature) painted in his twenties, much as he would have appeared during the 1793 Flanders campaign.

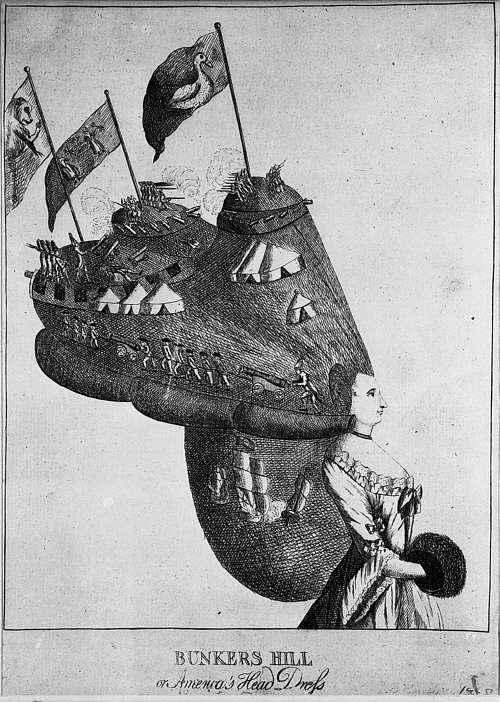

The British suffered a disastrous defeat at Bunker Hill in 1775. America’s success here was a gift to George III’s enemies, who lampooned Britain’s failure.

The opening of the battle of Germantown, with British troops around Cliveden manor. This drawing (detail shown) is one of a small number believed to show British uniforms accurately following Howe’s relaxation of dress regulations.

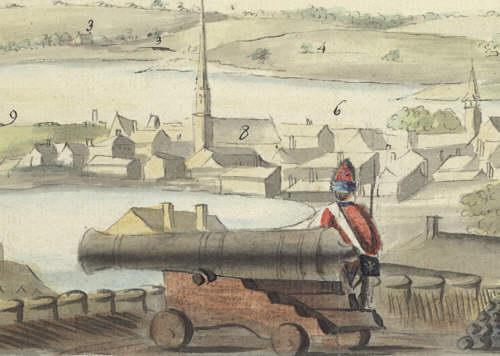

A detail from a Richard Williams sketch of Boston during the siege of 1775, in which at one point around 3,500 British soldiers faced an American force several times larger. The picture shows a soldier of the 23rd leaning against a cannon, apparently wearing his fusilier cap.