Galileo's Daughter (30 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

publish such a work

Between August of 1630, when the plague began permeating the streets of Florence, and the autumn of 1631, when Galileo settled in Arcetri, he gradually and with great difficulty broke the impasse that had stalled the publication of his

Dialogue

for another year.

Soon after Prince Cesi’s sudden midsummer death in 1630, Galileo made arrangements with a new publisher and printer in Florence. In September he secured official local permission from the Florentine bishop’s vicar, the Florentine inquisitor, and the grand duke’s official book reviewer and court censor—just as he would have done had he never gone to Rome. But then he felt obliged to inform Father Riccardi at the Vatican of these developments. The master of the Sacred Palace had, in all fairness, invested considerable time in reading and discussing the

Dialogue

with His Holiness and had raised specific points for Galileo to treat in the text. It was only proper to inform him by letter how the demise of the Roman publisher, Prince Cesi, coupled with the disruption of communications up and down the peninsula due to the plague outbreak, necessitated publication in Tuscany.

Father Riccardi’s reply let Galileo know that he had not relinquished his hold over the

Dialogue.

He still controlled its fate; in fact, he now wanted to read it again, and asked Galileo to send it back to him forthwith.

But how to send a bulky manuscript to Rome in these troubled times? The grand duke’s secretary of state warned Galileo that even ordinary letters might be stopped and confiscated at checkpoints, let alone whole volumes emanating from regions tainted by the epidemic.

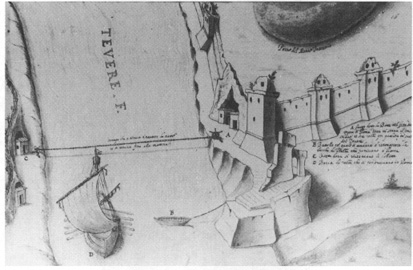

Plague barrier across the Tiber River where

boats were halted for inspection

Galileo wrote to Father Riccardi a second time, offering as a compromise to send him only the contested parts of the manuscript: the preface and the ending. Father Riccardi could change these however he saw fit—cutting, rewording, even inserting caveats “giving these thoughts of mine the labels of chimeras, dreams, paralogisms, and empty images.” As for the rest of the work, Galileo suggested it be reviewed this time within the city walls of Florence, by some authority of Father Riccardi’s choosing. Father Riccardi agreed.

In November 1630, Galileo duly turned over his

Dialogue

to the new designated reviewer in Florence, Fra Giacinto Stefani, who read the work minutely. “Indeed,” Galileo could now justly boast, “His Paternity has stated that at more than one place in my book tears came to his eyes when seeing with how much humility and reverent submission I defer to the authority of superiors, and he acknowledges (as do all those who have read the book) that I should be begged to publish such a work.”

But still Galileo could not publish it—was most assuredly prohibited from publishing it—until Father Riccardi blessed the preface and the ending. While Galileo waited, Father Riccardi dallied. The whole winter came and went without a word from Rome. “In the meantime the work stays in a corner,” Galileo observed bitterly, “and my life wastes away as I continue living in constant ill health.”

In March, Galileo appealed to the grand duke for help, “so that while I am still alive I may know the outcome of my long and hard work.” Ferdinando, feeling ever kindly disposed to the aging court philosopher who had tutored him in childhood, interceded. And Father Riccardi, who, as a native of Florence took special note of the grand duke’s interest, agreed at last in late May that all but the preface and conclusion could go on press while he continued to refine those parts.

“I want to remind you,” Father Riccardi wrote to the Florentine inquisitor on May 24, 1631, “that His Holiness thinks the title and subject should not focus on the ebb and flow of the sea but absolutely on the mathematical examination of the Copernican position on the Earth’s motion. . . . It must also be made clear that this work is written only to show that we do know all the arguments that can be advanced for this side, and that it was not for lack of knowledge that the decree [the Edict of 1616] was issued in Rome; this should be the gist of the book’s beginning and ending, which I will send from here properly revised.”

Thus the slow work of producing the large run of one thousand copies began in June. It took the entire month to set and print the first forty-eight of the

Dialogue

s five hundred pages.

Father Riccardi pronounced his last word on the subject July 19, when he forwarded the preface and ending particulars to the inquisitor at Florence. “In accordance with the order of His Holiness about Signor Galilei’s book,” Father Riccardi wrote in a brief cover letter, “I send you this beginning or preface to be placed on the first page; the author is free to change or embellish its verbal expressions as long as he keeps the substance of the content.” Father Riccardi’s enclosure, originally written by Galileo, had been very lightly edited. And Galileo now changed only one word; otherwise the suggested preface and the later published version agree exactly.

Rather than dictate the precise wording of the ending, after all that had transpired, Father Riccardi simply tacked on a coda to his text for the preface. “At the end,” these instructions stated, “one must have a peroration of the work in accordance with this preface. Signor Galilei must add the reasons pertaining to divine omnipotence which His Holiness gave him; these must quiet the intellect, even if there is no way out of the Pythagorean arguments.”

Father Riccardi knew just how compellingly Galileo had presented the “Pythagorean arguments,” as he called the Copernican view. Indeed, by the time readers turned the

Dialogue

s last page, they might well believe that Pythagoras and Copernicus had trounced Aristotle and Ptolemy for good. But of course Galileo was not allowed to leave the matter hanging there, as though admitting the absolute truth of the Copernican opinion. Short of divine revelation, only hypothetical truth would serve.

“After an infinity of cares, finally the preface to your distinguished work has been corrected,” Tuscan ambassador Francesco Niccolini wrote to Galileo, rejoicing with him after Father Riccardi, who was his wife’s cousin, had consented at last. “The Father Master of the Sacred Palace indeed deserves to be pitied, for exactly during these days when I was spurring and bothering him, he has suffered embarrassment and very great displeasure in regard to some other works recently published, as he must have done at other times too; he barely complied with our request, and only because of the reverence he feels for the Most Serene name of His Highness our Master and for his Most Serene House.”

Certainly Galileo owed a great debt to the intervention of young Ferdinando de’ Medici. He began to repay it with the special compliment of dedicating the

Dialogue

to the grand duke in a verbal bow—immediately preceding the crucial “Preface to the Discerning Reader” that Father Riccardi had stipulated.

“These dialogues of mine revolving principally around the works of Ptolemy and Copernicus,” wrote Galileo to Ferdinando,

it seemed to me that I should not dedicate them to anyone except Your Highness. For they set forth the teaching of these two men whom I consider the greatest minds ever to have left us such contemplations in their works; and, in order to avoid any loss of greatness, must be placed under the protection of the greatest support I know from which they can receive fame and patronage. And if those two men have shed so much light upon my understanding that this work of mine can in large part be called theirs, it may properly be said also to belong to Your Highness, whose liberal munificence has not only given me leisure and peace for writing, but whose effective assistance, never tired of favoring me, is the means by which it finally reaches publication.

Meanwhile, the exhaustive process of printing the

Dialogue

wore on. By mid-August, when one-third of the pages had piled up, Galileo told friends in Italy and France that he hoped to see the rest finished by November. But it took even longer, so that a total of nine months passed from the start of printing to the book’s completion in February 1632. Its wordy title filled a page:

Dialogue

of

Galileo Galilei, Lyncean

Special Mathematician of the University of Pisa

And Philosopher and Chief Mathematician

of the Most Serene

Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Where, in the meetings of four days, there is discussion

concerning the two

Chief Systems of the World,

Ptolemaic and Copernican,

Propounding inconclusively the philosophical and physical reasons

as much for one side as for the other.

No written words of encouragement from Suor Maria Celeste sped Galileo through this last leg of publication—simply because father and daughter now lived in such proximity that they found no reason to write. A short walk took him from his front door to her parlor grille in minutes, and if he was too busy or too troubled by his pains, he could send La Piera with news and a basket of something. After Suor Maria Celeste addressed her last letter to Galileo at Bellosguardo on August 30,1631, she may have imagined she need never write to her father again. But his move did not end their correspondence. It merely introduced a pause that lasted almost one and one-half years—until early in 1633, when the shock wave initiated by the

Dialogues

publication boomeranged and shattered Galileo’s peace in Arcetri.

At first, everything augured well for the book, which met with immense and immediate success. Galileo presented the first bound copy to the grand duke at the Pitti Palace on February 22, 1632. In Florence the book sold out as quickly as it entered the shops. Galileo also sent copies to friends in other cities, such as Bologna, where a fellow mathematician commented, “Wherever I begin, I can’t put it down.”

Frontispiece of Galileo’s Dialogue; the three figures represent, from left to right, Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Copernicus

The copies destined for Rome, however, were held up until May on the advice of Ambassador Niccolini, who apologized that current Roman quarantine regulations required all shipments of imported books to be dismantled and fumigated—and no one wanted to see the

Dialogue

subjected to such treatment. Galileo got around this obstacle by sending several presentation copies into Rome via the luggage of a traveling friend, who distributed them to various luminaries including Francesco Cardinal Barberini. Galileo’s longtime confrere, Benedetto Castelli, now “Father Mathematician of His Holiness,” read one of these copies.

“I still have it by me,” Castelli wrote to Galileo on May 29,1632, “having read it from cover to cover to my infinite amazement and delight; and I read parts of it to friends of good taste to their marvel and always more to my delight, more to my amazement, and with always more profit to myself.”

A young and as yet unknown student of Castelli’s named Evangelista Torricelli

*

wrote Galileo in the summer of 1632 to say he had been converted to Copernicanism by the

Dialogue.

The Jesuit fathers with whom he had formerly studied, he told his new idol, had also taken great pleasure in the book, though naturally they could not corroborate the opinions of Copernicus.

Some Jesuit astronomers, however, especially Father Christopher Scheiner, the “Apelles” who claimed to have discovered sunspots before Galileo, reacted violently to the

Dialogue.

Scheiner’s own latest book, the long-delayed

Rosa Ursina,

which finally appeared in April 1631, had lambasted Galileo with offensive language. Now Scheiner was living in Rome, having learned to speak Italian, and he harangued Father Riccardi to have the

Dialogue

banned. On top of the anger he had apparently stewed in his breast since the sunspot debate two decades earlier, Scheiner felt newly annoyed by what he inferred to be a fresh personal slander against him in Galileo’s book.

Soon the

Dialogue

provoked Pope Urban’s ire as well. It came to his attention at a most inopportune moment, when his profligate spending on war efforts was well on its way to doubling the papal debt, and when his fears of Spanish intrigue against him had reached new heights of paranoia. At a private consistory Urban had held with the cardinals on March 8,1632, the Vatican ambassador to Spain, Gaspare Cardinal Borgia, had openly censured the pontiff’s failure to back King Philip IV in the Thirty Years’ War against the German Protestants. The pope’s behavior, Cardinal Borgia charged, evinced his inability to defend the Church—even his unwillingness to do so. Hasty efforts by Urban’s family cardinals to silence the Spanish sympathizer almost came to physical blows before the Swiss Guard entered the chamber to restore order.