Galileo's Daughter (29 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

Suor Maria Celeste further nursed Galileo by plying him with every new plague preventative she could fabricate in her apothecary shop or procure by other means. Although she did not explain how she managed to obtain it, she sent him a bottle of healing water from the venerated Abbess Ursula of Pistoia—a liqueur that Ursula’s own followers placed on a par with holy relics and dared not distribute to outsiders. “Therefore I urge you, Sire, to put your faith in this remedy, because if you believe as strongly as you have indicated in my poor prayers, then all the more greatly can you trust in a soul so saintly, assuring yourself that by her merits you will escape every danger.”

She could not similarly endorse another offering—an electuary of dried figs, nuts, rue leaves, and salt, “held together with as much honey as was needed”—but still she prepared it for him, pressed it on him, and prescribed its usage: “You may take it every morning, before eating, in a dose about the size of a walnut, followed immediately by drinking a little Greek or other good wine, and they say it provides a marvelous defense.” Indeed, this formula carried the official endorsement of the Magistracy of Public Health.

Galileo reciprocated with periodic gifts of money and food— including meats, sweets, and even a special spinach dish he cooked himself especially for her—as well as by giving her a warm quilt to replace the one she had yielded to Suor Arcangela, miscellaneous containers and glass vials for her apothecary work, and citrons that she returned to him as quickly as she could, candied to his liking. When he forgot to send a promised telescope, she reminded him to put it in the basket next time. This gentle reprimand—her only surviving mention of any scientific instrument—hints that she may have borrowed a peek at the moons of Jupiter or the horns of Venus, despite the duties that ate up all her time.

Galileo apparently accompanied the tokens of his paternal love with frank praise for her abilities, though she deflected these compliments: “I am confounded to hear that you save my letters,” she remarked, “and I suspect that the great love you bear me makes them seem more accomplished than they really are.”

In December 1630, the

tramontana

—the cold wind from the Apennines—beat into Tuscany with force, effectively locking Galileo indoors. Unable to visit the convent as he had wished, he sent news of his health via his new housekeeper, La Piera, whose prudence and capability impressed Suor Maria Celeste. Now she calmed herself to think that her father was well looked after, even if the attention came from a hired employee instead of her brother’s family.

Suor Maria Celeste had disapproved of Vincenzio’s flight but held her tongue for fear he would leave anyway, and that her intrusion would only upset him. Now she worried what might happen to her brother’s empty, unguarded house in his absence. At the same time she encouraged Galileo to continue to play the generous father—“especially in perpetuating your beneficence toward those who repay you with ingratitude, for truly this action, being so rife with difficulty, is all the more perfect and virtuous.”

In early January, the magistracy sent out nuncios and trumpeters to declare a general quarantine of forty days’ duration, beginning on the tenth of the month. Sensing a decline in the epidemic’s virulence, the authorities hoped to hasten it to its end by this drastic measure. The imposition of the general quarantine limited travel in or out of the city even more strictly than before, and also forbade ordinary household visits among neighbors and friends. The only permissible reasons for venturing out of one’s doors now were to go to church or to buy food or medicines. Since the ordinance applied to Florence and all its surrounding communities, including Prato, Vincenzio could not have returned easily during these six weeks even if he had wanted to.

Vincenzio’s new baby, Carlo, arrived on January 20, but Galileo did not hear a timely announcement of the birth, or any word at all from his absent son and daughter-in-law regarding their welfare in this time of constant sorrow. Suor Maria Celeste’s concern naturally stayed focused on the firstborn, nicknamed “Galileino,” who had been introduced to his aunts and cousin at the convent in his infancy. Now she repeatedly asked her father to bring the boy back to visit her again, as soon as it was safe to do so. “I want you to give one more kiss,” she would say in closing a letter, “to Galileino for my love,” and she sent him pinecones to play with, expecting he could amuse himself extracting the nuts. She baked little cookies for the other child now in Galileo’s care—his grandniece Virginia, the daughter of Vincenzio Landucci and his sickly wife—but Suor Maria Celeste could not help her father place “La Virginia” at San Matteo.

“I am terribly disturbed by my inability to grant you satisfaction as I would have liked to do in taking custody here of La Virginia, for whom I feel such fondness, considering all the sweet relief and diversion she has been to you, Sire. However I know that our superiors have declared themselves totally opposed to our admitting young girls, either as nuns or as charges, because the extreme poverty of our Convent, with which you are well acquainted, Sire, makes it a struggle to sustain those of us who are already here, let alone consider the addition of new mouths to feed.”

With her sister-in-law Sestilia in hiding at Montemurlo and still incommunicado after the quarantine ended, Suor Maria Celeste resumed the upkeep of Galileo’s wardrobe. “I am returning the bleached collars, which, on account of their being so frayed, refused to turn out as exquisitely as I would have wished: if you need anything else please remember that nothing in the world brings me greater joy than serving you, just as you for your part seem to devote yourself to doting on me and satisfying any request, since you provide for my every need with such solicitude.”

If her claustration posed no impediment to their emotional closeness, the distance between Bellosguardo and Arcetri now raised a formidable barrier. “I find my thoughts stay fixed on you day and night, and many times I regret the great remove that bars me from being able to hear daily news of you, as I would so desire.”

Galileo suffered this same lonely longing. The prospect of the mule trek from his house to her convent, though it hadn’t seemed so lengthy or arduous at first, of late too often held him back. He decided to move to Arcetri.

With her characteristic ingenuity and energy, Suor Maria Celeste canvassed the local real estate market from inside the walls of San Matteo. She discovered only a few available properties, however, because wealthy city dwellers cherished their villas in Arcetri as weekend escapes to the country, and because the working farms of the region passed down through families, as they had for generations. Moreover, some lands were deeded to the Church under a variety of legal situations, so that the question of their ownership generated considerable dispute.

“As far as I have been able to determine,” she reported of her earliest efforts, “the priest of Monteripaldi has no jurisdiction over the villa of Signora Dianora Landi save for a single field. I understand, however, that the house was assigned as a dowry to a chapel of the Church of Santa Maria del Fiore, and this is the reason that our same Signora Dianora finds herself in litigation. . . . I have also learned that Mannelli’s villa is not yet taken, but is available for rent. This is a very beautiful property, and people say its air is the best in the whole region. I do not believe that you will lack the opportunity to secure it, Sire, if events turn out as well as you and I so strongly desire.”

At Eastertime, when the plague appeared to have spent itself, Galileo’s prodigal son returned at last with his family and joined in the househunting activities, which continued all through that spring and summer. From his city home, Vincenzio could walk up to Arcetri in just a quarter of an hour to appraise prospective sites on Galileo’s behalf.

“Sunday morning brought Vincenzio here to see the Perini’s villa, and as Vincenzio himself will no doubt tell you, Sire, the buyer will have every advantage. . . . I come to beg you not to let this opportunity slip through your fingers, for God knows when another such as this will present itself, now that we see how people who own lands in these parts cling to them.” But Villa Perini fell into another’s hands.

Then, in early August, her searching turned up a property literally around the corner from the convent—even closer than her mother’s house on the Ponte Corvo had been to Galileo’s Via Vignali home during her childhood in Padua.

“Because I do so desire the grace of your moving closer to us, Sire, I am continually trying to learn when places here in our vicinity are to be let. And now I hear anew of the availability of the villa of Signor Esau Martellini, which lies on the Piano dei Giullari, and adjacent to us. I wanted to call it to your attention, Sire, so that you could make inquiries to see if by chance it might suit you, which I would love, hoping that with this proximity I would not be so deprived of news of you, as happens to me now, this being a situation I tolerate most unwillingly.”

The Martellini villa on the Piano dei Giullari, or field of minstrels, occupied such an ideal site atop the western slope of Arcetri that it had been dubbed “II Gioiello”—the jewel. Built in the 1300s by gentry who were establishing a farm near the convent, it narrowly escaped total destruction during the Siege of Florence two centuries later, when the Medici returned to power by force after one of their periodic banishments from the city. Between October 1529 and August 1530, forty thousand mostly Spanish troops, controlled by the prince of Orange and the Medici pope Clement VII, camped in the hills around the city, unwilling to enter combat but hoping to starve the Florentines into submission. The bubonic plague, attacking again at that same time, helped the army carry out its plan. Despite the lack of open hostilities, the mere presence of all those soldiers for ten straight months left the landscape a scene of devastation.

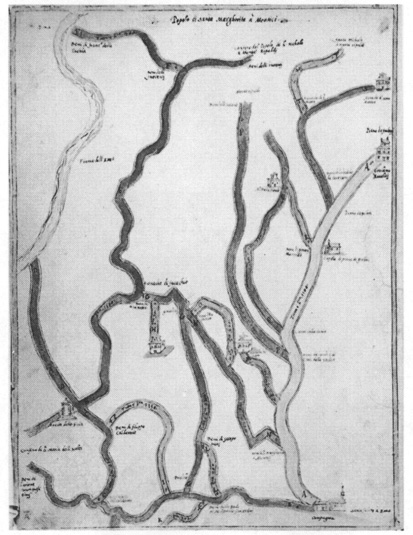

A fresco painted in the mid-1500s in the Palazzo Vecchio, where the triumphant Medici family resided before moving to the Pitti Palace, shows the region of the Piano dei Giullari during the siege, with military tents popping up like anthills and II Gioiello clearly identifiable among the neighborhood houses.

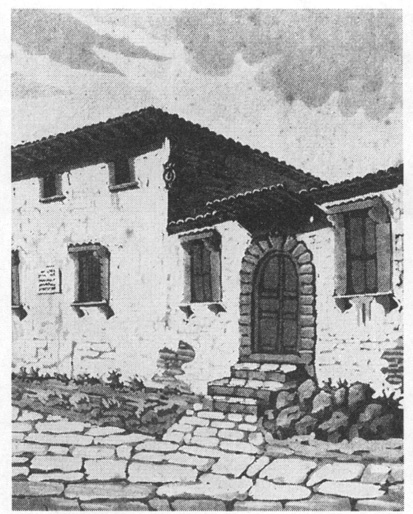

Galileo’s house, II Gioiello, in Arcetri,

where he lived from 1631 to 1642

II Gioiello stood in ruins for several years after the siege. Then it was refurbished and rebuilt, with thick stone walls that met at the corners of rooms in graceful arches called lunettes, with floors of brick laid out in herringbone patterns, with intricate wooden ceilings and wide windows that were shuttered, barred, and set so low they seemed to kneel into the street. Four very large rooms and three smaller ones shared the ground floor, with a kitchen and wine cellar below, and rooms for two servants above.

What Galileo loved best about the place was the sunny garden to the south of the house, reliably watered by the

tramontana,

and the semi-enclosed loggia facing the courtyard near the well, where potted fruit trees might pass the colder months in safety.

“We lament the time away from you, Sire, covetous of the pleasure we would have drawn from this day, had we found ourselves all together in each other’s company. But, if it please God, I expect that this will soon come to pass, and in the meanwhile I enjoy the hope of having you here always near us.”

Sixteenth-century map of Arcetri; the convent of San Matteo is at

lower right, II Gioiello at crossroads above

The contract Galileo signed with Signor Martellini on September 22,1631, set the rent for II Gioiello at thirty-five

scudi

per year— only a fraction of the hundred he had paid at Bellosguardo—due in two equal installments every May and November. Approaching his seventieth year, he expected to live out the remainder of his days in these idyllic surroundings.

From the window of the room Galileo chose for his study, he could see the Convent of San Matteo just a stone’s throw away, downhill to the left of the vineyard.

That I should

be begged to