Galileo's Daughter (36 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

Even if Urban’s former love for Galileo had remained untarnished, instead of being tainted by betrayal, he could not now deny the obvious. The accused had defended a condemned doctrine. Nor could Urban risk any overt leniency toward Galileo, considering how the Thirty Years’ War had raised doubts about his own guardianship of the Catholic faith. And no matter how much Urban admired the achievements of Galileo’s lifetime, he had never shared his outlook on the ultimate goal of scientific discovery. Whereas Galileo believed that Nature followed a Divine order, which revealed its hidden pattern to the persistent investigator, Urban refused to limit his omnipotent God to logical consistency. Every effect in Nature, as the handiwork of God, could claim its own fantastic foundation, and each of these would necessarily exceed the limits of human imagining—even of a mind as gifted as Galileo’s.

Faith vested

in the miraculous

Madonna

of Impruneta

All the while Galileo sojourned in Rome, the plague regathered its strength in Florence. Suor Maria Celeste heard regularly from Signor Rondinelli of new developments and new cases reported to the local Magistracy of Public Health. Thus, as much as she pined to have her father back at II Gioiello, she counseled him, out of concern for his welfare, to enjoy the hospitality of his Roman hosts as long as possible. She even suggested he celebrate his eventual release from the Holy Office by making another pilgrimage to the Casa Santa in Loreto—anything to delay his homecoming until the pestilence deserted Tuscany altogether.

The walls of San Matteo continued to keep the plague at bay. Inside them, other sicknesses assailed the sisters, and all manner of non-health-related problems as well, such as the debacle of Suor Arcangela’s term as provider. In this role, which fell to each of the nuns on a rotating basis, Suor Arcangela assumed charge of all outside food purchases for the convent for one year. As little as the nuns ate, the cost of twelve months’ provisions for thirty women could easily reach one hundred

scudi,

most of which the provider had to pay out of her own pocket, even if that pocket were empty. Some previous providers had resorted to desperate schemes to produce the requisite sums, and a few had circumvented Suor Maria Celeste to appeal directly to Galileo for emergency assistance. Now his own daughter found herself in this plight as her term of office neared its end. But just as Suor Arcangela had prevailed on others to help her shoulder the physical demands of the job, owing to her frequent spells and infirmities, she deferred the worrisome financial burden as well.

“I have another kindness to ask of you,” Suor Maria Celeste was thus forced to address Galileo in April while he faced foes far from home, “not for myself, but for Suor Arcangela, who, by the grace of God, three weeks from today, which will be the last day of this month, must leave the office of Provider, in which capacity up till now she has spent one hundred

scudi

and fallen into debt; and being obliged to leave 25

scudi

in reserve for the new Provider, not having anywhere else to turn, I beg your leave, with your permission, Sire, to help her out with the money of yours that I hold, so that this ship can bring itself safely into port, whereas truly, without your help, it would not complete so much as half its voyage.”

Even after Galileo approved the release of those funds, however, Suor Maria Celeste had to approach him for more. “For Suor Arcangela up till now I have paid close to 40, part of which I had received as a loan from Suor Luisa, and part from our allowance, of which there remains a balance of 16

scudi

to draw upon for all of May. Suor Oretta spent 50

scudi:

Now we are sorely pressed and I do not know where else to turn, and since the Lord God keeps you in this life for our support, I take advantage of this blessing and seize upon it to beseech you, Sire, that with God’s love you free me from the worry that harasses me, by lending me whatever amount of money you can until next year comes around, at which time we will recover our losses by collecting from those who must pay the expenses then, and thereby repay you.”

On the back of this letter Galileo wrote himself a reminder—of something he might not easily forget—as though to aid a memory already taxed by age and stress. The note said, “Suor Maria Celeste needs money immediately.” And, as usual, he saw to that need.

As soon as she had settled her sister’s debts with their father’s help, Suor Maria Celeste learned that Suor Arcangela’s next proposed position would put her in charge of the convent’s wine cellar. “This current year was to bring Suor Arcangela’s turn as Cellarer, an office that gave me much to ponder,” Suor Maria Celeste told Galileo. She feared Suor Arcangela would abase the position as she had that of provider, through inattention, and perhaps abuse it, too, by usurping her authority as cellarer to overindulge in drink. “Indeed I secured the Mother Abbess’s pardon that it not be given to her by pleading various excuses; and instead she was made Draper, obliging her to bleach and keep count of the tablecloths and towels in the Convent.”

When she heard, probably from Galileo himself, how freely fine vintages flowed at the Niccolinis’ table, Suor Maria Celeste admonished her father not to confuse himself with wine—the beverage he had long fondly described as “light held together by moisture.” She feared the large quantities he’d grown accustomed to imbibing might aggravate his worsening pains. “The evil contagion still persists,” she wrote on May 14 in response to Galileo’s hint of how he might soon be headed homeward, “but they say only a few people die of it and the hope is that it must come to an end when the Madonna of Impruneta is carried in procession to Florence for this purpose.”

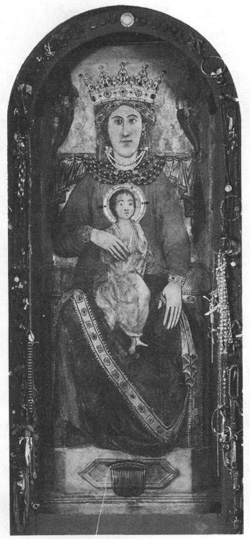

The Madonna of Impruneta, an icon brought to Tuscany in the first century, had ministered to the victims of sundry disasters. Since the Black Death in 1348, not a flood nor a drought nor a famine, battle, or epidemic had erupted in Florence that could not be mitigated by carrying the miraculous Madonna of Impruneta from her small church in a neighboring village down into the great cathedrals of the city. In May of 1633, Grand Duke Ferdinando called for the sacred image to retrace that long path once more, to rout the resurgent plague. The Magistracy of Public Health, however, attentive to the danger of congregation in time of contagion, issued an ordinance on May 20 to limit the number of faithful—especially women and children—who could join the procession.

The Madonna of Impruneta

“As for your returning here under these prevailing conditions,” Suor Maria Celeste worried in her next letter, “I can guarantee you neither resolution nor assurance on account of the contagious pestilence, whose end is so urgently desired that all the faith of the city of Florence is now vested in the Most Holy Madonna, and to this effect this morning with great solemnity her miraculous Image was carried from Impruneta to Florence, where it is expected to stay for 3 days, and we cherish the hope that during its return journey we will enjoy the privilege of seeing her.”

From May 20 to 23, the Madonna of Impruneta passed through the streets of Florence laid waste by the plague, and spent her nights as the guest of three churches that had vied for that honor. The holy image depicted Mary seated on a throne, wearing a red dress and jeweled crown, holding the baby Jesus in the folds of her blue lap robe. About her neck, real necklaces—one of pearls, the other of precious stones—embossed the flat surface of the icon, the whole of which stood inside a red frame rounded at the top like an archway. Eight men carried the poles holding the ornate canopy above the Madonna, and at least another twelve shared the weight and the glory of bearing the table on which her venerated form rested.

When leaving Florence, Suor Maria Celeste recounted, “the image of the Most Holy Madonna of Impruneta came into our Church; a grace truly worthy of note, because she was passing from the Piano [dei Giullari], so that she had to come this way, going back along the whole length of that road you know so well, Sire, and weighing in excess of 700

libbre

[about one-quarter ton] with the tabernacle and adornments; its size rendering it unable to fit through our gate, it became necessary to break the wall of the courtyard, and raise the doorway of the Church, which we accomplished with great readiness for such an occasion.”

*

In the weeks following the Madonna’s visit, the death toll from the plague alternately dipped and climbed, so that the full extent of the miracle she had wrought did not become clear until September 17, 1633, when the authorities declared Florence officially free of contamination. In early June, however, as the day of Galileo’s judgment approached, Suor Maria Celeste still heard word of seven or eight plague fatalities every day. And Signor Rondinelli warned her that the open country around Rome would be closed to travelers for the summer months as a further precaution to preserve the safety of the Holy City. If Galileo were not allowed to leave the embassy in the very near future, he would be stuck there at least until autumn.

In mid-June she once more cautioned her father against hasty departure, urging him to stay put, away from “these perils, which in spite of everything continue and may even be multiplying; and in consequence an order has come to our Monastery, and to others as well, from the Commissioners of Health, stating that for a period of 40 days we must, two nuns at a time, pray continuously day and night beseeching His Divine Majesty for freedom from this scourge. We received alms of 25

scudi

from the commissioners for our prayers, and today marks the fourth day since our vigil began.”

All the worry Suor Maria Celeste expended over the plague danger facing her father was unoccasioned, however, since the Inquisition had no intention of releasing Galileo any time soon.

On June 16, Pope Urban VIII presided over a meeting of the cardinal inquisitors. Urban had absorbed the official report summarizing the Galileo affair from the first accusations against the philosopher in 1615, through the publication of his book, up to his recent defense and plea for mercy. Now His Holiness demanded that Galileo be interrogated “on intent"—to determine, technically by torture if necessary, his true purpose in writing the

Dialogue.

The book itself could not escape censure in any case, the pontiff averred, and would assuredly be prohibited. As for Galileo, he would have to serve a prison term and perform penance. His public humiliation would warn all Christendom of the folly of disobeying orders and gainsaying Holy Scripture dictated by the mouth of God.

“To give you news of everything about the house,” Suor Maria Celeste wrote on June 18, unaware of the awful turn of events in Rome,

I will start from the dovecote, where since Lent the pigeons have been brooding; the first pair to be hatched were devoured one night by some animal, and the pigeon who had been setting them was found draped over a rafter half eaten, and completely eviscerated, on which account La Piera assumed the culprit to be some bird of prey; and the other frightened pigeons would not go back there, but, as La Piera kept on feeding them they have since recovered themselves, and now two more are brooding.

The orange trees bore few flowers, which La Piera pressed, and she tells me she has drawn a whole pitcherful of orange water. The capers, when the time comes, will be sufficient to suit you, Sire. The lettuce that was sown according to your instructions never came up, and in its place La Piera planted beans that she claims are quite beautiful, and coming lastly to the chickpeas, it seems the hare will win the largest share, he having already begun to make off with them.

The broad beans are set out to dry, and their stalks fed for breakfast to the little mule, who has become so haughty that she refuses to carry anyone, and has several times thrown poor Geppo so as to make him turn somersaults, but gently, since he was not hurt. Sestilia’s brother Ascanio once asked to ride her out, though when he approached the gate to Prato he decided to turn back, never having gained the upper hand over the obstinate creature to make her proceed, as she perhaps disdains to be ridden by others, finding herself without her true master.

On the morning of June 21, ushered into the chambers of the commissary general for the fourth and final time, Galileo endured his examination on intent by Father Maculano.

Q:

Whether he had anything to say.

A:

I have nothing to say.

Q:

Whether he holds or has held, and for how long, that the Sun is the center of the world and the Earth is not the center of the world but moves also with diurnal motion.

A:

A long time ago, that is, before the decision of the Holy Congregation of the Index, and before I was issued that injunction, I was undecided and regarded the two opinions, those of Ptolemy and Copernicus, as disputable, because either the one or the other could be true in Nature. But after the said decision, assured by the prudence of the authorities, all my uncertainty stopped, and I held, as I still hold, as most true and indisputable, Ptolemy’s opinion, namely the stability of the Earth and the motion of the Sun.