Georgette Heyer's Regency World (12 page)

Read Georgette Heyer's Regency World Online

Authors: Jennifer Kloester

- To be thought ‘fast’ or to show a want of conduct was the worst possible social stigma.

- A lady never forced herself upon a man’s notice.

- No lady was to be seen driving or walking down St James’s Street where several of the gentlemen’s clubs were located.

- No lady was to walk or drive unattended down Piccadilly.

- No female was to refer to any of those male activities about which a lady should feign ignorance.

- A husband was expected to keep his indecorous activities and less cultured friends separate from his marriage.

- A wife was expected to be blind to her husband’s affairs.

- A married woman could take a lover once she had presented her husband with an heir and so long as she was discreet about her extramarital relationships.

- Women were expected to be ignorant of any proposed duel.

- A lady did not engage in any activity that might give rise to gossip.

- Subjects of an intimate nature such as childbirth were never discussed publicly.

- When out socially a lady did not wear a shawl for warmth no matter how cold the weather.

- A gentleman was expected to immediately pay his gambling debts, or any debt of honour.

- It was unacceptable to owe money to a stranger.

- It was acceptable to owe money to a tradesperson.

- It was considered bad form to borrow money from a woman.

- A female did not engage in finance or commerce if she had a man, such as a husband, father or brother, to do it for her.

- A lady did not visit a moneylender or a pawnbroker.

- Extremes of emotion and public outbursts were unacceptable, although it could be acceptable for a woman to have the vapours, faint, or suffer from hysteria if confronted by vulgarity or an unpleasant scene.

- A well-bred person behaved with courteous dignity to acquaintance and stranger alike, but kept at arm’s length any who presumed too great a familiarity. Icy politeness was a well-bred man’s or woman’s best weapon in putting ‘vulgar mushrooms’ in their place.

- A well-bred person maintained an elegance of manner and deportment.

- A well-bred person walked upright, stood and moved with grace and ease.

- A well-bred person was never awkward in either manner or behaviour and could respond to any social situation with calm assurance.

- A well-bred person was never pretentious or ostentatious.

- Vulgarity was unacceptable in any form and was to be continually guarded against.

- Indiscretions, liaisons and outrageous behaviour were forgivable but vulgarity never was.

Scandal!

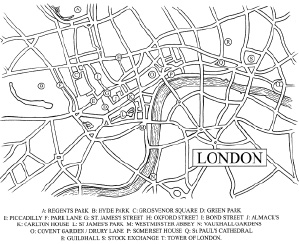

For many in the Regency, and particularly the upper classes, reputation was everything. Scandal was the means by which most errant individuals lost their social standing but it was also the lifeblood of high society; the delight of both ladies and gentlemen who exchanged crim. con. stories on the dance floor, over a hand of cards or even at Almack’s, as Meg did with her brother Freddy in

Cotillion

. Criminal conversation (crim. con.), a euphemism for adultery, was common practice among the

haut ton

during the Regency, and the Prince Regent and several of the royal Dukes were among the worst offenders. Their various affairs, monetary embarrassments, debaucheries and excessively hedonistic behaviour were frequently scandalous and the delight of many of the great caricaturists of the day. Satirical cartoons by Rowlandson, Cruikshank and Gillray would appear en masse in London print-shop windows, drawing huge crowds of appreciative onlookers. In 1785, while still the Prince of Wales, the Regent had married his mistress Mrs Fitzherbert. The marriage was illegal because, as a Catholic, Mrs Fitzherbert was ineligible to wed a future English monarch, and the Prince was not yet twenty-five and therefore in breach of the Royal Marriage Act. Yet they lived together for several years until the Prince’s extravagance forced a change. In 1795, huge debts saw the Prince contract a hasty marriage to his cousin, Caroline of Brunswick, in return for the payment of his debts and a larger allowance from parliament. The couple separated soon after the wedding, but not before Caroline had conceived a daughter and heir to the throne, Charlotte. Never comfortable in his role as either husband or father, throughout the Regency the Prince behaved in a way that remained a constant source of scandal. His high-handed behaviour after his daughter had broken her engagement to the Prince of Orange was a source of eager gossip at Lord and Lady Lynton’s first assembly in

A Civil Contract

. Ever self-indulgent, despite his many attributes, the Prince engaged in a series of affairs with older women, spent vast sums on cosmetics, clothes, food, wine and entertainment, and on pet projects such as Carlton House and the Brighton Pavilion.

Money was a constant problem for the royal Princes, most of whom spent lavishly and were continually in debt. The Regent’s brother, the Duke of York, became embroiled in a huge monetary scandal when it was discovered that his mistress, Mary Anne Clarke, had been profiting from the illegal sale of military commissions and promotions. As Commander-in-Chief of the army the Duke signed off the lists of new commissions and it was alleged that his mistress could not have engaged in selling these without his cooperation. The Duke was forced to face a parliamentary inquiry and was eventually cleared of the charge but not before his love letters had been read out and reprinted in a series of best-selling scandal sheets which eventually forced him to resign from the army. Another brother, the Duke of Clarence, well known for his dalliances and in particular for his ten illegitimate children with his long-time mistress, the actress Mrs Jordan, sought relief from his debts by proposing to the very rich Miss Taverner in

Regency Buck

. Even more outrageous was the Duke of Cumberland’s reputation—he was thought by some to have committed incest with his sister Sophia and to have murdered his valet.

Outside the royal family, society was constantly abuzz with the latest on-dits, discussing every sordid or delicious detail of the newest infidelity, elopement, illegitimate offspring, bankruptcy, social faux pas or other dishonourable act committed by a member of the

ton

. Whether society forgave or tolerated indiscretions mainly depended upon the birth and circumstances of the perpetrator. Society looked with disapproval on many of Lady Barbara Childe’s escapades in

An Infamous Army

but her birth and her relationship with her grandfather, the Duke of Avon, saw her invariably accepted as a member of the

ton

. As long as the proprieties were met on the surface, what went on behind the scenes was often overlooked. Dalliances, affairs, mistresses and lovers could be acceptable as long as they were discreet; one could commit adultery, and it could be public knowledge, so long as the relationship was maintained in private and neither philanderer flaunted their affair in public. It was the very conspicuous and often hysterical manifestation of Lady Caroline Lamb’s passionate obsession with Lord Byron that society deplored and which brought about her social downfall. Above all, high society disdained open displays of emotion and any form of vulgarity. By indulging her feelings for all to see and publishing a scandalous novel,

Glenarvon

, in which she satirised those in society whom she perceived to be her enemies, Caroline committed the ultimate social sin. One of the main characters in the book and the object of her desperate passion, Lord Byron, was himself the subject of several scandalous reports which engrossed and titillated society for several years. Having been society’s darling after the publication of

Childe Harold

and

The Corsair

(although Judith Taverner in

Regency Buck

preferred the poetry to the poet!), Byron’s rumoured incestuous relationship with his half-sister, Augusta Leigh, his treatment of his wife Annabella Milbanke, his bouts of extreme behaviour, his debts, and his eventual separation from his wife, led society to turn their backs on the once-adored poet and he left England in 1816, never to return. Many young Regency men, including Oswald Denny in

Venetia

, aspired to achieve the dark passion of Byron’s

Corsair

by wearing their hair wildly ruffled, knotting a silk handkerchief around their necks and adopting a brooding, soulful look intended to arouse the romantic longings of any well-read or romantic female.

Dancing

Whether at a ball at Almack’s or a masquerade at the Opera House or Covent Garden, a Vauxhall Gardens fête, a private party or a public assembly, dancing formed an important and integral part of Regency life. All classes of society engaged in the dance in both private and public venues and frequently in celebration of an important event such as a birthday, a coming-of-age or a marriage. Dancing was one of the few social activities in which men and women could participate together. For an upper-class debutante, balls and assemblies were one of the primary places to meet a potential husband and to demonstrate the grace, deportment, musicality and ability to master the intricate steps of the most popular dances of the day that were the characteristics of a ‘proper’ education. In

Cotillion

, for example, Lady Buckhaven prevailed upon her brother Freddy to teach their cousin Kitty the steps of the waltz and the quadrille in order to further her chances of making a good match.

During the Regency the four principal dances were the country-dance, the cotillion, the quadrille and, more commonly after Tsar Alexander had danced it at Almack’s in 1814, the waltz. The English country-dance had been popular since the seventeenth century and allowed for a large number of dancers in each set. Men and women formed two lines, facing each other, with the couple at the top of the set being ‘first’. As the dance progressed, the top couple would move one spot further down the line after each figure and eventually take their place at the bottom of the set, by which time the original last couple had become the first. The cotillion was a form of French

contredanse

which was itself a version of the English country-dance. Performed by eight dancers in a square formation, the cotillion was executed using a series of ‘figures’ and ‘changes’. A regular cotillion consisted of ten changes with a figure performed between each change. The changes were generally the same within each cotillion, but the figures between them were different for each dance. Similar to the cotillion, the quadrille was introduced early in the Regency and consisted of five figures and no changes using the same square formation of eight dancers. When it was first introduced the quadrille proved difficult for many unwary dancers and so cards were produced with directions for the correct execution of the various figures and changes. Almack’s provided dance cards for those less expert dancers but, although a useful device, it was also an unwieldy one when used during the actual dance. The steps of the quadrille were French and at some assemblies the master of ceremonies or the band leader would call out the figures to the dancers to make it easier for the less experienced members of a formation to perform the steps correctly. Executing steps such as the

chassé, jetté, coupe balote, glissade

or the

pas de basque

with elegance and grace required a high degree of skill. Marianne Bolderwood at her first ball in

The Quiet Gentleman

found that she had to concentrate carefully on the steps of the quadrille while her partner, Gervase, executed even the most difficult steps with considerable grace.

As the less difficult country-dances gradually made way for the cotillions and quadrilles, dancing masters or ‘caper-merchants’ were frequently employed to teach the steps and sequences in private homes, prior to the lady or gentleman attempting them in public. Some of the great ladies of the day, such as the Duchess of Devonshire, organised morning classes in their homes where several young women could learn the dances together. It was the Duchess’s example that convinced Mrs Chartley, the rector’s wife in

The Nonesuch

, to grant permission for her carefully brought up daughter Patience to participate in the planned morning dances at Staples where the young ladies would learn the waltz and practise the other fashionable dances. After its introduction at Almack’s, the waltz had become generally popular by 1815 and was danced in most English ballrooms, despite the disapproval of some who held it to be too intimate and strenuous a dance for delicate debutantes. The enormous change from dances performed in sets to one danced by a mere couple, and in such close proximity to each other, meant that many young women only danced the waltz at private balls or at assemblies when they had been formally introduced to a ‘suitable’ partner.

The Theatre

The theatre was enormously popular during the Regency and most large towns had at least one playhouse. In London, the two great theatres of the period were Covent Garden and the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, both of which held a monopoly on the production of straight plays as a result of a royal patent granted by Charles II in 1660. Most theatres only opened for six months of the year and, apart from Drury Lane and Covent Garden, were restricted by their licences to presenting pantomimes, musicals and farces. This did not prevent them from drawing large crowds, however, and the attraction of continually changing programmes and new and enticing ‘spectaculars’ saw as many as twenty thousand people attending the various theatres each night during the Season. Tickets for the pit at the Haymarket theatre sold for 10s. 6d. while a hired box could cost as much as £2,500 for the Season. Members of the upper class frequently rented a box, to which they could invite friends or family, promote a suitable match for a son or daughter, or simply take the opportunity to show off their jewels and other costly attire while enjoying an evening’s entertainment.