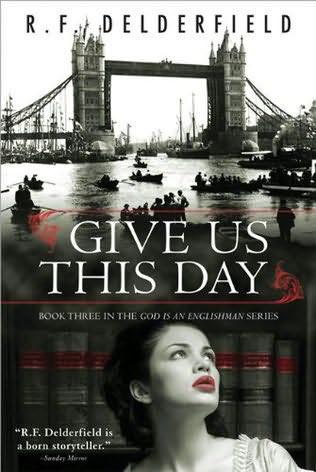

Give Us This Day

Copyright © 1973, 2010 by R. F. Delderfield

Cover and internal design © 2010 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Cyanotype Book Architects

Cover images © Francis Frith & Co/Getty Images; Compassionate Eye Foundation/Katie Huisman/Getty Images

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Originally published in Great Britain by Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1973.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Delderfield, R. F. (Ronald Frederick)

Give us this day / by R. F. Delderfield.

p. cm.

1. England—Social life and customs—Fiction. 2. England—History—19th century—Fiction. I. Title. PR6007.E36G58 2010 823’.912—dc22

2009049939

AREA MANAGERS OF SWANN-ON-WHEELS

1906–1914

Western Wedge—

Albert Bickford

The Link—

Coreless

Southern Square—

Young Rookwood

The Funnel—

Edward Swann

Mountain Square—

Enoch and Shadrach (stepsons of Bryn Lovell)

West Midlands—

Luke Wickstead

Northeastern Region—

Markby

Scotland—

Higson

Ireland—

Clinton Coles (Jack-o’-Lantern)

Northern Ireland—

Son of Jake Higson

The Kentish Triangle—

Godsall

Tom Tiddler’s Land—

Dockett

The Polygon—

Rudi (son of George Swann)

PART ONE

Three Score Years and Ten

One

Clash of Symbols

O

n the morning of his seventieth birthday, in the Jubilee month of June 1897, Adam Swann, onetime cavalryman, subsequently haulier extraordinary, now landscaper and connoisseur, picked up his Times, turned his back on an erupting household, and stumped down the curving drive to his favourite summer vantage point, a knoll sixty feet above the level of the lake overlooking the rustic building entered on the Tryst estate map as “The Hermitage.”

His wife, Henrietta, glimpsing his disapproving back as he emerged on the far side of the lilac clump, applauded his abrupt departure. Never much of a family man, preoccupied year by year with his own extravagant and mildly eccentric occupations, he had a habit of getting under her feet whenever she was organising a social event and preparation for a family occasion on this scale demanded concentration.

By her reckoning there would be a score sitting down to dinner, without counting some of the younger grandchildren, who might be allowed to stay up in honour of the occasion. She knew very well that he would regard a Swann muster, scheduled for dinner that night, as little more than an obligatory family ritual, but she was also aware that he would humour her and the girls by going through the motions. Admittedly it was his birthday and an important milestone in what she never ceased to regard as anything but a long and incredibly adventurous journey, but she knew him well enough, after thirty-nine years of marriage, to face the fact that celebrations of this kind had no real significance for him. Whenever he gave his mind to anything it needed far more substance and permanence than an evening of feasting, a few toasts, a general exchange of family gossip. That kind of thing, to his way of thinking, was a woman’s business and such males who enjoyed it were, to use another phrase of his, “Men who had run out of steam” —an odd metaphor in the mouth of a man who had made his pile out of draught horses.

As for him, Henrietta decided, watching his deliberate, slightly halting progress down the drive and then hard right over the turf to the knoll, he would almost surely die with a full head of steam. Increasing age, and retirement from the city life eight years before, had done little to slow him down and encourage the repose most successful men of affairs regarded as their right on the far side of the hill. He had never changed much and now he never would. Indeed, to her and to everyone who knew him well, he was still the same thrustful Adam of her youth, of a time when he had come riding over a fold of Seddon Moor in the drought summer of 1858 and surprised her, an eighteen-year-old runaway from home, washing herself in a puddle. He was still a dreamer and an actor out of dreams. Still a man who, unless his creative faculties were fully stretched, became moody and at odds with himself and everyone about him. In the years that had passed since he had surrendered his network to his second son, George, she had adjusted to the fact that old age, and the loss of a leg, had diminished neither his physical nor mental energies. He continued to make many of his local journeys on horseback. He still followed, through acres of newsprint, the odysseys of his hardfisted countrymen and the egregious antics of their commercial imitators overseas. All that had really happened, when he moved over to make room for George, was the exchange of one obsession for another. Once it had been his network. Now it was the embellishment and reshaping of his estate that had filled the vacuum created by his retirement. He still made occasional demands on her as a bed-mate, but she was long since reconciled to the fact that there was a part of him, the creative part, that was cordoned off, as sacrosanct as Bluebeard’s necropolis, even from George, his business heir, and from Giles, who did duty for his father’s social and political conscience; even from network cronies out of his adventurous past, who occasionally visited him and were conducted on an inspection of the changes he had wrought in this sector of the Weald since taking it into his head to make Tryst one of the showplaces of the county. There were some wives, she supposed, who would have been incapable of acquiescing to this area of privacy in a man for whom they had borne five sons and four daughters. Luckily for both of them Henrietta Swann was not one of them. She had always been aware both of her limitations and her true functions and had never quarrelled with them, or not seriously. To reign as consort of a man whose name was a household word was more than she had ever expected of life and fulfilment had been hers for a very long time now. Her place in his heart was assured and their relationship, since she had passed the age of child-bearing and become a grandmother, was as ordered as the stars in their courses. Any woman who wanted more than that was out looking for trouble.

* * *

He paused on the threshold of The Hermitage, doing battle with his sentimentality. The thatched, timbered building was a Swann museum, housing practical personal mementoes he had carted away from his Thameside tower when he retired in the spring of 1889. He was not a man who revered the past, but the exhibits in here symbolised his achievements and it struck him that a man had a right to sentimentalise a little on his seventieth birthday. He went inside the shady, circular barn and glanced about him, his eyes adjusting to the dimness after the June sunlight.

Originally, when he first conceived the notion of a Swann depository, there had been no more than half-a-dozen items. Since then many more had been added, the most impressive being the first coach built frigate the firm of Blunderstone had delivered to him when he started his freight line in ‘58. It looked old-fashioned now, a low-slung, broad-axled structure, with a central harness pole for the two Clydesdales that had pulled it all over the Home Counties. He had kept its brasswork polished, and the hubcaps winked at him conspiratorially. He glanced up at the framed maps of the original regions, drawn in his own hand after that first exhaustive canvass of his head clerk, Tybalt, probing what they might expect from haulage clients in competition with the ever-expanding railways of that race-away era.

The maps seemed to him very crude now, but he saw them for what they were: the spring from which everything about him welled. Today, with the network almost forty years old, they certainly qualified as museum pieces, for George, his son, had abolished the regions as such, promoting a variety of other drastic changes that had rocketed some of the older area managers into premature retirement. The original regions had had queer, quirkish names, yet another fancy of their creator—the Western Wedge; the Crescents on the east coast; the Northern Triangle, where it lapped over the Tweed into Scotland; Tom Tiddler’s Land, that was the Isle of Wight; and the like. Now these had been condensed into huge areas, embracing the entire British Isles—south, north, far north, and Ireland. Prosaic names and very typical of George, who was still known, among the older waggoners, as the New Broom.

He thought about George, isolating his good points and his bad. The good far outweighed the bad, for the boy had shown tremendous application and a high degree of imagination in the expansion period, although he had not as yet succeeded in banishing the horse and replacing it with one or other of those lumbering, ungainly machines that people in transport said would soon be commonplace on the roads. Rumour reached him that the New Broom had bitten off more than he could chew in this respect. Here and there, egged on by the younger managers, he had experimented with machines spawned by that snorting, fume-spewing monster he had lugged all the way from Vienna ten years before. The older men had jeered at them and their scepticism had seemed justified. Four times in one month waggon teams had to be harnessed to them to tow them home and Head Office had been taxed to explain a pile-up of delivery delays. But George’s other changes had been happier. Frigates, the medium-weight vehicles of the kind that stood here, had been all but withdrawn and their teams used to increase the firm’s quota of light transport, resulting, so they said, in a wider range of deliveries and a faster service for customers trading in more portable types of goods. George had also made his peace with the railways, contracting with them in every region to offload goods at junctions and then subcontracting for most of their local deliveries. He had also broken the despotic power of the regional men at a stroke, subdividing the depot functions and installing sub-managers answerable, individually, for house-removals, railway traffic, and the holiday brake-service. Well, Adam mused, you would look for this kind of thing in a new broom, especially one like George, whose amiability masked a ruthlessness and single-mindedness not unlike Adam’s own in his younger days.

He went out of The Hermitage and ascended the tree-clad knoll that gave a view of the frontal vista of house and grounds. It was a prospect that always gave him the greatest satisfaction. Other men had contributed to his founding of Swann-on-Wheels but this, the transformation of a rundown manor house and its surrounding fifty-odd acres, had been his alone, expressing his developing aesthetic taste over all the years he had lived there. It proclaimed the three phases of his life. Young trees, from all over the world, bore witness to his years in the East up to the age of thirty, when he had dreamed of a positive participation in the era and made up his mind to renounce a game of hit-and-miss with the Queen’s enemies and the near-certainty of getting his head blown off. The neatness and precision of the layout, with its lawns, spaced clumps of flowering shrubs, belts of soft timber, lake, and decorative stonework signified his middle years and his unflagging passion for creativity within precise terms of reference. The colour, form, and enduring mellowness of the scene, with the old stone house crouching under the spur of rock, were indicative of his tendency to opt for the attainable in life, an unconscious compromise between the turbulence of youth and the sobriety of a man who had made his pile and put his feet up. Surveying it, he thought,

That’s my doing, by God! It owes nothing to any man save me

, but he had second thoughts about this. No man, perhaps, but at least one woman: his wife, Henrietta, child of a coarse, comic old rascal now in his dotage among a wilderness of stinking chimney-pots up north. Sam Rawlinson, who had made two fortunes to Adam’s one, and thoughts of Sam led directly to his daughter, the tough, resolute, high-spirited girl he had found on a moor and carried off like a freebooter’s prize on the rump of his mare.

Regard for her, generous acknowledgment of her fitness for a freebooter’s bride, had grown on him year by year. A girl he had married almost absentmindedly in the very earliest days of the network, who had been able, surprisingly, to stir his senses every time he watched her take her clothes off; even now, at a time of life when a man with a truncated leg was lucky to be mobile, much less intrigued by the spectacle of her wriggling free of all those pleats and flounces.

The thought made him smile again as he remembered a coffee-house quip of thirty years ago, something about “that chap Swann reinvesting half his annual profits in his wife’s wardrobe.” Well, for anyone who cared to know, he had never been over-impressed by Henrietta Rawlinson dressed for a soiree or a garden-party. He had always seen her as ripe for a bedroom romp, and a ready means of escape from the cares of empire. More of a mistress, one might say, despite five sons and four daughters, each born in that crouching old house under the spur—and a very rewarding mistress at that, considering the profound ignorance of her contemporaries concerning the basic needs of a full-blooded man of affairs. All but two of their children had been by-products of these moments of release, but George and his younger brother Giles were exceptions.

And even this was odd when you thought about it. George, his commercial heir, had been sired almost deliberately the night of their truce at the one important crisis in the relationship of man and wife. George he had always seen as a tacit pledge between them, acknowledgment that he should look to his concerns as provider and she to hers as gaffer of that rambling house up yonder. And so it had transpired, for Henrietta’s maturity had flowered from that moment on, reaching its apogee three years later, with the loss of his leg in that railway accident over at Staplehurst, and the birth, forty weeks later, of Giles, keeper of the Swann conscience.

He turned half-left, glancing across at the belt of fir trees marking the limit of the estate to the northwest, the spot where, in a matter of hours before the accident, the pair of them had found something elusive in their relationship in the way of a hayfìeld frolic, belonging to a time before the British put on their long, trade faces, their tall hats, and that mock-modesty ensemble that everyone expected of a prosperous middle-class merchant and his consort. And out of it, miraculously, had emerged Giles, the family sobersides, whose cast of thought was alien to the extrovert Swanns of Tryst, and whose absorption into the firm had proved a counterpoise to George’s enterprise. For Giles, to Adam’s mind at least, supplied the balance so necessary to any large organisation employing men and materials to make money. Giles was there to safeguard the Swann dictum that every unit counted for something in terms of human dignity and had proved his worth in every area where the waggons rolled. Giles was the adjuster, if that was the right word, between profit and people.

* * *

His random thoughts, gathering momentum, descended from the pinnacle of the particular to the plain of the general, so that he saw both himself and his concerns as a microcosm of the Empire, currently preparing for an orgy of tribal breast-beating, the like of which had never been witnessed since the era of Roman triumphs. A Diamond Jubilee. An Imperial milestone. A strident reminder to all the world that the victors of Waterloo and the battle for world markets were there to stay, for another century or more, perhaps forever.

The papers were full of it. The streets of every city, town, and village in the country were garlanded for it. From every corner of the world, coloured red on the maps by conquest and chicanery, a tide of popinjays flowed Londonwards, to share in what promised to be the most emphatic event of the century. Homage to a symbol, the pedants would call it, but a symbol of what? Of racial supremacy? Or trade and till-ringing? Of military triumph on a hundred sterile plains, deserts and in as many steamy river bottoms? He had never really known, despite his diligent observation of the antics of four tribes over five decades. Once, a long time ago, he had seen it all as a matter of trade following the drum in search of new markets and fresh sources of raw material essential possibly for a nation that lived on its workshops. But forty years of trading had taught him that this was no more than an expedient fiction. For now, when inflated jacks-in-office and glory-seekers gobbled up remote islands, he knew that the helmsman was way off course, and that most of these acquisitions would cost, in the long run, far more than they could ever yield.