gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (31 page)

Plate 27

. Tenth-century encaustic painting from Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, showing, left, the disciple Thaddeus, and, right, the disciple curing Abgar, king of Edessa, using a handkerchief that Jesus wiped across his face. Thaddeus continued his journey, reaching Armenia in AD 43/45. At Yeghrdut, near Mush in historical Armenia (eastern Turkey), he is said to have deposited a piece of the Tree of Life, as well as other important holy relics.

Plate 28

. The remains of the Yeghrdut monastery, now known as Dera Sor (the Red Church), on the northern slopes of the Eastern Taurus Mountains of eastern Turkey. It was here that Thaddeus apparently deposited his precious cache of holy relics.

Plate 29

. The west wall of Dera Sor, the ruins of the Yeghrdut monastery, said to have been located in the Garden of Eden itself. Muslims and Christians alike came here to sit beneath its holy tree and partake of its sacred waters to rejuvenate their bodies by as much as twenty years.

Plate 30

. The view from Dera Sor, the ruins of the Yeghrdut monastery in eastern Turkey, looking out over the plain of Mush, through which flows the Euphrates River. Is this the true site of the Garden of Eden as described in the book of Genesis?

Plate 31

. Bingöl Mountain in the Armenian Highlands of eastern Turkey, the source of the Araxes and Euphrates rivers. Evidence suggests it is the true site of the Mountain of Assembly of the Watchers, as well as Kharsag, the home of the Anunnaki in Sumerian tradition. It can be identified also with Charaxio, the mountain in which Seth concealed the secrets of Adam, according to Sethian Gnostic tradition.

Plate 32

. Two examples of snake-headed statues, found in graves belonging to the Ubaid culture, which thrived in Mesopotamia ca. 5000–4100 BC. They are now thought to be representations of a long-headed elite group that controlled the Bingöl/Lake Van obsidian trade during the earlier Halaf period, ca. 6000–5000 BC. Did this elite group model itself on a memory of those responsible for the construction of Göbekli Tepe?

Plate 33

. The Alevi holy site of Hızır Çes̨mesi (the Fountain of Hızır), at Muska (modern Bes̨ikkaya Köyü) in the northern foothills of the Bingöl massif in eastern Turkey. Is this the original Ab’i Hayat, the Waters of Life, where Alexander the Great is said to have gained immortality upon reaching Bingöl? The building on the right is a dream incubation house, where people come to spend the night and dream of Hızır, the Turkish form of al-Khidr, the Green One.

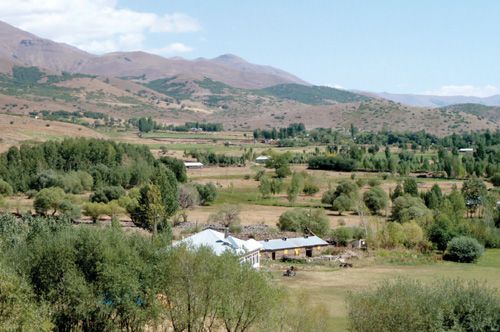

Plate 34

. View from Muska looking south toward the western foothills of the Bingöl massif. Is this the original location of Dilmun, the paradisiacal realm of the Anunnaki gods of ancient Sumer, as well as the site of the terrestrial Paradise in Judeo-Christian tradition?

21

THE SOLUTREAN CONNECTION

T

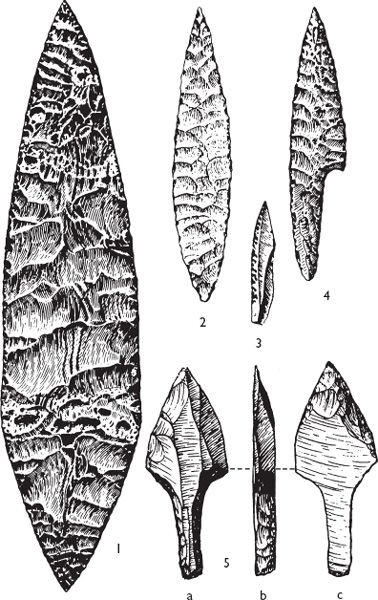

he Solutreans are the key to the emergence of high culture across Central and Western Europe during the Upper Paleolithic age. Their campsites, work stations, and cave sites date to between 25,000 and 16,500 years ago and span from England (especially East Anglia) in the north, to northern Spain, Portugal, and France in the south. Like the Swiderians much later, the Solutreans mastered the use of surface pressure flaking to create highly unique willow-leaf-shaped projectile points and much larger, laurel-leaf-shaped lance heads, which share similarities to the Swiderians’ own leaflike points. Moreover, like the Swiderians, the Solutreans—who were themselves reindeer hunters—fashioned shouldered (i.e., tanged) points, with either one or two shoulders (see figure 21.1 on p. 178) and thus almost certainly used bows and arrows.

So thin and so finely worked are the Solutreans’ laurel-leaf lance heads, which can be up to 14 inches (36 centimeters) in length, translucent, and just a quarter of an inch (0.6 centimeter) thick (see

plate 25

), that Sharon McKern, an anthropological consultant, writing with her husband, Dr. Thomas McKern, professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas, was moved to observe: “This delicately flaked tool technique is the most aesthetic—and the most mysterious—known from prehistoric times.”

1

The fact that a number of these unique blades have been found in groups within caches and are regularly made of nonlocal, exotic materials (including chalcedony, jasper, and quartz crystal) has led to speculation that they were not used for any practical purpose but instead served some ritual or symbolic function.

Figure 21.1. A selection of finely worked Solutrean points, ca. 20,000– 14,500 BC, many finished using the pressure flaking technique.

RIMUTÈ RIMANTIENÈ’S COMMENTS

So what exactly is the connection between the Solutreans and the later Swiderians? In 1996 Lithuanian archaeologist Rimutè Rimantienè proposed grouping together the various North European cultures that thrived in the Upper Paleolithic under a single umbrella term—the Baltic Magdalenian, or the “Group of Baltic Magdalenian cultures,” because they all display signs of having a common origin.

2

Just one culture was to be excluded from the list, and this was the Swiderian, “where the relations with the Solutrean are outstanding, though also indirect.”

3

Rimantienè recognized the remarkable similarities between the stone tool technologies of the two cultures and felt the need to put this in writing, even though making such a connection was clearly anathema in the scholarly community in which she moved.

*8

The problem is simple—the Swiderian culture does not enter the scene until the beginning of the Younger Dryas period, ca. 10,900 BC. This is thirty-five hundred years

after

the Solutreans disappear from the pages of European history to make way for the Magdalenians, an altogether different culture whose principal legacy is the beautiful Ice Age cave art of southwest Europe.

As to the fate of the Solutreans, no one really knows, although some prehistorians propose that they departed for the North European Plain when the reindeer herds migrated northward at the end of the last ice age. If so, then they might easily have formed the core of much later reindeer-hunting traditions, in particular the Brommian-Lyngby cultures of Denmark and the Scandinavian Peninsula. Certainly, laurel-leaf points and shouldered points, identical to those of the Solutreans, have been found in the south and west of Sweden and Norway,

4

suggesting strongly that this is where the Solutreans came looking for the reindeer herds. Here their descendants would have remained until the onset of the Younger Dryas mini ice age, when with the worsening climate they were forced southward into Central Europe, paving the way for the emergence of the Swiderian tradition in places such as Poland, Slovakia, and the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains.