God's War: A New History of the Crusades (142 page)

Read God's War: A New History of the Crusades Online

Authors: Christopher Tyerman

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Military History, #European History, #Medieval Literature, #21st Century, #Religion, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Religious History

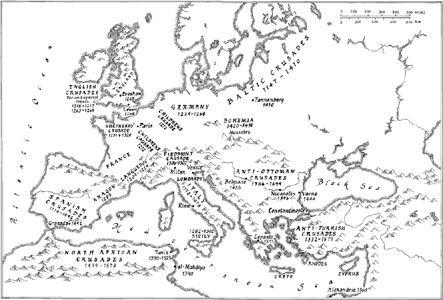

24. Crusades in Europe

Such occasional civic ceremonies were matched by more permanent demonstrations of crusade commitment: regular festivals, confraternities and gilds. Crusade interest in the 1330s at Tournai in north-eastern France may have been associated with the week-long festival of the Holy Cross that ended on 14 September, Holy Cross Day, a date closely linked with crusading.

6

While the lay orders of chivalry provided for the tastes and aspirations of the nobility, non-noble organizations emerged to cater for a wider public. Lay confraternities to channel devotion and material support can be found in France as early as the 1240s. In Italy, similar confraternities served the papalist cause. In Norfolk, England, in 1384 two gilds were founded, St Christopher’s at Norwich and St Mary’s at Wiggenhall, that began their meetings with prayers for the recovery of the Holy Land. If other English gilds’ sponsorship of Jerusalem pilgrimages are a guide, these expressions of spiritual sociability could act as foci to arrange crusaders’ practical needs as well as to give

crucesignati

members a good send off.

7

The Parisian

confrarie

of the Holy Sepulchre demonstrated how interest could be fostered by overlapping local, political and social networks. Founded with a lavish ceremony on Holy Cross Day 1317 in the church of the Holy Cross in Paris, the confraternity’s patron was Louis I count of Clermont and duke of Bourbon, grandfather of the 1390 al-Mahdiya

commander and the French royal prince most frequently associated with French crusade plans for twenty years after 1316. Between 1325 and 1327, a church was built for the

confrarie

, dedicated to the Holy Sepulchre. This came to house a number of Holy Land relics, including three pieces of the True Cross, a key to one of the gates of Jerusalem, an arm of St George and a piece of stone from the Holy Sepulchre itself. Although attracting royalty and nobility, the core of the membership, apparently over 1,000 in the 1330s, were Parisian

bourgeois

, many of whom had taken the cross at Philip IV’s great ceremony of 1313. The function of the confraternity was to provide these

crucesignati

with a way to structure and display their continued devotion and, no doubt, their special status and public association with the great. The patronage of courtiers lent snobbish value to membership as well as widening the circles of nobles’ political clientage. The

confrarie

also acted as a charity, with the unachieved aim of founding a hospital for Holy Land pilgrims. Such institutions and buildings formed a tangible daily reminder of the

negotium crucis

, exploiting a variety of highly effective pressures: charity; the cult of relics; the elitism of a prominent civic social club; public display; the social allure of nobles and non-nobles mingling as

confréres

the imprimatur of the church.

8

Such institutional context helped crusading continue as a social as well as religious phenomenon.

Before the gradual fading of realistic hopes of recovering the Holy Land, active planning could generate wider popular engagement, occasionally with disruptive consequences. Preaching, offers of indulgences and taxation could still ignite popular response from those on or beyond the margins of accepted political society. In 1309, in reaction to a small crusade expedition run by the Hospitallers, engaged in completing their conquest of Rhodes, apparently large numbers from England, the Low Countries and Germany took the cross and converged on Mediterranean ports. The papal-Hospitaller campaign, designed to relieve Armenia and Cyprus, only departed early in 1310. It had not been planned as a mass crusade, even if some hoped it would constitute an advance guard of much larger force, a dual strategy urged by contemporary theorists. In 1308, Pope Clement V had granted crusade privileges to those who helped the Hospitallers. A discrepancy arose between organizers and public. Official interest was in raising money to pay for a largely professional army; over two years in the archdiocese of York nearly £500 was collected, primarily from indulgences. However, the

loss of the Holy Land in 1291, combined with more recent hopes of a Mongol liberation of Jerusalem, encouraged a wider participation. While hostile conservative chroniclers dismissed the recruits as unauthorized, underfunded and indisciplined, of lowly peasant or urban status, the social mix in this ‘popular’ crusade, as in 1212 and 1251, was broader than clerical snobbery and hierarchic defensiveness implied. From England, those licensed to depart for the Holy Land ranged from nobles to a surgeon. Some of the unofficial levies were sufficiently conversant with the political mechanics of crusading to petition the pope to summon a general crusade; he refused. Larceny and thuggery provided a familiar accompaniment to the progress of these bands southwards. As well as demonstrating the commonplace of violence and lawlessness on the fringes of mass demonstrations that disrupt the tenor of local communities, the alleged outrages reflected the crusaders’ lack of funds and the impossibility of mounting a mass crusade without elite leadership and massive treasure. The existence of a pool of willing, if not particularly able, recruits cannot be doubted. The crusade industry had created its own market with customers unwilling to be fobbed off with spiritually passive or exclusively financial bargains.

9

In 1320, the links between well-publicized official crusade policy and unauthorized crusade enthusiasm were just as clear. In the winter of 1319–20, Philip V of France held a series of conferences in Paris to discuss his crusade plans. A year earlier he had appointed Louis of Clermont as leader of the proposed French advance guard. In the spring, groups of so-called ‘pastoureaux’, indicating countrymen, if not literally shepherds, from northern France, converged on Paris around Easter. News of Philip’s crusade plans may have penetrated these regions through the summonses to the winter assemblies, especially Normandy, Vermandois, Anjou, Picardy and the Ile de France. Economic conditions in some of these rural areas had been appalling. Peace with Flanders in 1319 and the hope generated by prospects of better times and a new crusade may have helped set these bands on the road to Paris. As in 1212 and 1251, many of those who set out were young men, with loose domestic ties, possibly without jobs or tenancies to sustain them through the severe agrarian depression. Yet their association with court policy was evident. A Parisian observer noted many of them came from Normandy, heavily represented at the crusade conferences.

10

Some marched behind the banner of Louis of Clermont, not improbably with his consent,

hinting at the summons of the wider civil society in support of a troubled political elite. Pope John XXII expressed surprise that Philip V had acquiesced in the activities of the ‘pastoureaux’.

11

Initially, churches gave them food and shelter. There was talk of using the marchers on a projected campaign to Italy by Philip V’s cousin, Philip of Valois, the future Philip VI, hardly a task for a criminal mob. Parisians let them pass unmolested. The bands were well organized, some professing clear objectives, such as Aigues Mortes, whence they wished to sail to the Holy Land, indicating the power of nostalgia, precedent, history and legend, here the dominant memory of St Louis. As the bands headed towards the Midi, lack of assistance, realization of their isolation and resentment at the parasitic privileges of those deemed to have exploited or failed the crusade were channelled into violence. Wealthy laity and clergy were attacked; Jews were massacred. Such mayhem acted as a symptom as much as a cause of disintegration, a sign of the desperation to sustain themselves through acts of chastisement, in their eyes moral deeds that had to serve as substitutes for the greatest moral deed of all, the crusade.

The extent to which the French regime was complicit in encouraging the ‘pastoureaux’ in order to put pressure on the pope to grant crusade money to Philip V remains conjectural. Nevertheless, the French ‘pastou-reaux’ did not operate entirely outside the perimeter of official crusade policy. They challenge any idea of popular enthusiasm for the Holy Land crusade declining or retreating into a day-dream for the chivalric classes. Neither were the ‘pastoureaux’ enacting a social revolt in disguise. The social critique was subtler, a shared acceptance with the elites of moral purposes coupled with harsh criticism of how those elites pursued them. Public failure, not social exploitation, lay at the heart of the grievances of 1320.

12

The concept of the crusade could exceptionally be harnessed to radical social demands. In the spring of 1514, Archbishop Thomas Bakocz of Esztergom, with the vigorous assistance of the Observant Franciscans, hastily arranged a crusade in Hungary against the Turks, partly as a sop for his ego, battered by his narrow defeat at the papal conclave the previous year. Reminiscent of scenes in 1456, the preaching struck a chord with hard-pressed rural peasantry, townsmen and students. The economic situation was dire, hitting market towns and livestock herdsmen as much as peasants and tenant farmers. The crusade was sold as

redemptive both spiritually and socially. The Hungarian nobility proved hostile, uninterested in supporting war with the Turks, eager to retain revenue designated for the defence of the Turkish frontier and angry at the potential loss of agricultural labour for hay making and harvest. Almost immediately, the crusaders turned on the nobles. Displaying a strong sense of community, the crusader army, led by the minor nobleman George Dozsa and allegedly numbering tens of thousands, began a reign of terror against nobles and their property across the Hungarian plain. Despite Archbishop Bakocz cancelling the crusade as soon as he saw how it was developing, the crusaders continued their rampage, while maintaining their devotion to the cross, crusading privileges, the king and the pope. As so often in sixteenth-century Europe, this was a very conservative social revolt. On 22 May 1514 an army of nobles was defeated, the crusaders finally being crushed only in mid-July at Timisoara (Temesvar). Atrocities had been committed on both sides, the final one the most horrific. Dozsa was placed on a burning stake, platform or throne, a red-hot iron ‘crown’ placed on his head and his followers compelled to bite chunks out of his burning flesh and drink his blood, all this accompanied by singing, dancing and a carnival atmosphere. Dozsa was being branded a traitor to nation, class and faith, precisely what he publicly denied. The 1514 crusade had been officially sanctioned. It attracted large numbers from a wide underclass of civil society with sensitive political antennae. They blamed the nobles – accurately – for failing to pursue the crusade, but took it further. The Hungarian nobles were branded as worse than Turks, a traditional charge levelled against those who impeded the

negotium Dei

. Only this time, those making these judgements were not popes, princes or prelates, but minor aristocrats and peasants who had taken too literally the message of the cross as a sign of emancipation.

13

It may be significant that one later Hungarian word for rebel,

kuruc

, is derived from

crux

and may enshrine a long cultural memory of the grim events of the spring and summer of 1514.

14

The eccentric and gruesome Hungarian crusade revolt revealed the crusade as not necessarily the preserve of the social elites. However, it also illustrated how crusading motifs could be employed in contexts not essentially connected with holy war and, conversely, how initially tangential or non-crusading emotions and aspirations could find expression in crusade language and forms, however eccentrically or

tendentiously construed, in this case by the radical Observant Franciscans. Equally, the behaviour of the Hungarian nobles in 1514 points to the absurdity of generalizing about crusade popularity or social embrace. The Hungarian elite became tepid at formal crusading at a time when the Habsburgs, heirs of the dukes of Burgundy but especially in their Iberian manifestation, eagerly employed the fully panoply of rhetoric, theology and privileges, tempered by their own brand of monarchical messianism. The Iberian revival found fewer echoes in fifteenth-century England when the collapse of the credibility of the Prussian crusade was not replaced by any new feasible object for action, except for those who became Hospitallers. In France, the crusade retained its lustre, but was inextricably caught up in the burgeoning religion of monarchy. As a bond of community and a justification for war, in many places and times crusading, having provided a model, became superseded. The very lack of such confidence in their share of national identity may have encouraged the less grand elements in Hungary to define their action against the Turks and then their nobles so tenaciously in terms of traditional crusading.