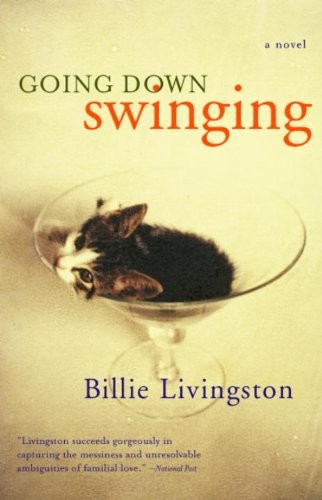

Going Down Swinging

Praise for Going Down Swinging

“Livingston has pared her prose down to a tough, unflinching realism … mastering multiple points of view [and] deftly switching narrative voices in alternating chapters. … [She] reveals an unflinching eye and a formidable grasp of the mysteries of the human heart.”

—

The Vancouver Sun

“Going Down Swinging

is written in a highly evocative, wryly humorous prose. An absorbing tale of growing up disadvantaged with an alcoholic mother and an absent father, the novel is no coming-of-age weeper. … Livingston does a subtle and effective job of making the specialness of [a] strange and loving—and, in the best of times, fun—family unit flame into memorable life.”

—

The Toronto Star

“Billie Livingston vividly captures the heady romance of mother-daughter love, so strengthening in its unconditional acceptance and support, and so wretchedly debilitating in its blindness.”

—

The Hamilton Spectator

“The novel is driven by the clear and believable voices of its characters. Eilleen’s fears and desires and shames are told without false sentiment. Livingston’s book is a humane and political look at the world of hard knocks. … We discover there are no happy endings, just the possibility of fresh beginnings.”

—

New Brunswick Telegraph—Journal

“Eilleen and Grace—from whose points of view the story is alternately told—are small fictional masterpieces.”

—

Vancouver Courier

“[Livingston] captures the view from the mountain tops and the valley bottoms—and the journeys in between—in

Going Down Swinging

It all rings so very true and so very moving.”

—

The Strathmore Standard

Eilleen One

NOVEMBER 1972

N

O ONE EVER

believes they’ll sink So Low.

So Low

is someone else’s life, someone else’s man, someone else’s job. Everyone imagines little rubber bands hooked at the shoulder, springing back to safety just before the life-sucking bedrock.

Now Danny’s gone, your man, the guy you called husband. And you’re wandering in the haze between dazed and terrified. Flat broke. Flat out. Just flat; a reasonable hand-drawn facsimile of your former self. Somewhere along the line, you got weak and sickly, sucked dry. And he got necessary.

He’s always had a kind of crafty power—everyone wanted him and no one could push him. Not until they took him away, at least. Why did you start up with him again? If he hadn’t’ve been busted two years ago, you would’ve dumped him. So then, what’d you go and do in the meantime, you idiot—went out with one too many assholes until even Danny sounded good.

And Charlie’s gone and fucked off too—mind you, for all intents and purposes, she’s been gone two years now. Couldn’t wait to get out of the house—all that hash and acid floating around the streets, all those micro-minis and fishnet stockings. Fourteen years old when Danny ended up in jail, and without him to make her, she wouldn’t do a goddamn thing you said. She got pissed off, sometimes smug, always bitching, sitting around lazy or walking off and coming home late. It wasn’t supposed to be that way. She’s been cruel ever since. She won’t look after you and you can’t look after her and she won’t let you. She’s sick of you and your wine and pills, and screaming retaliation every time she mouths back. Thank god for Grace. She loves you. She clambers all over you and says so.

Now it’s just the two of you again, you’ll celebrate her seventh this month, alone. And you’ll have to work, find work for bills, and landlords and food and rent and Grace and the hydro and the phone. You’ve been sober all of one week now—too sick to get a job again, to go back to teaching—that was someone else, that woman. Sick when you do drink, sick when you don’t. Nauseous and sensitive—skin hurts, and your hair, you can feel each hair move when the air shifts. And the mess, everything’s dirty—you can’t get up the strength or the will to clean. You’ll have to get welfare again. At least for now.

You pace all morning, trying to get up the nerve, the strength to go down to the Welfare office. Pick out the right clothes, now, or they won’t believe you. They’d have to be morons. He never kept you like a queen—you refused all hot merchandise in the form of furs and jewels—stupid-stupid-stupid.

By noon, a social worker is looking over your application. He’s sweet somehow, so careful with you. His little round bald head, his soft voice. Seems foreign now, another language; gentle, articulate. He puts gs on the ends of his verbs. None of Danny’s crowd could ever string together five words of proper English. It’s always

boozin’, screwin’, fuckin’—

or more likely

f(ee-iz)uckin’—

they’ve got to throw that

ee-iz

smack in the middle of anything illegal or obscene, just in case the walls have ears. But you can’t imagine this man ever uses those words.

He gives you the emergency assistance cheque. You’ll soon receive a cheque every month: $269.67. For you and one dependant. You start to cry. The social worker doesn’t understand. Or maybe he does. He just doesn’t know what to do but yank tissue after tissue. Each one gives a sympathetic little gasp as it pulls free, until both you and the Kleenex box are hoarse from hyperventilation.

Guilt is coursing through your arms, up your neck and pounding at the back of your eyeballs until you want to scream, rip it out of your wrists like ropy veins. It’s pointless, guilt is useless. It just wasn’t meant to be, that’s all. You and Danny shouldn’t have bothered again and Charlie should’ve just kept doing whatever she was doing: screwing with her foster mother’s head or robbing every kid in the group home blind. Christ, stop thinking such shit—it’s not her fault, it’s not your fault, it just is. You just couldn’t get along—used to start up as soon as you came in the door, the screaming. Fights were getting worse and worse and you were scared it was going to get as bad as it got before she took off the first time. Scared of getting your hair pulled and your mouth slapped and scared of doing it all back.

The night before Charlie left for good, you didn’t come home. But it was about time that kid took some responsibility. Maybe it was time

she

found out what it was like looking after a seven-year-old in this insane asylum with a man who wouldn’t come home for three days running half the time. It was your turn to bugger off and take a break. It’s not like you were drinking much. And you were trying to go to

AA

now and then.

Just before noon when you came in, and no one was home; it was a school day and Danny was probably out with his cronies somewhere pretending to be a real estate agent. You were standing in the kitchen. The room looked as if it’d spat up on itself: a chewed on dried-up piece of bread lay in a puddle of crumbs on the table beside a chewed-on twisted straw, dirty pots on three out of four burners, white plates covered with dried orange slop, macaroni pieces on counters, a milk carton tipped on its side, spoons in every pot, forks on every plate, a butcher knife on the counter and cheesy orange fingerprints all over the fridge door. You started to seethe.

Christ, I live in a house full of assholes

. They couldn’t even make a pretence of cleaning up, couldn’t even stack dishes in the sink, not even near the sink—they’re punishing you, you thought, this is what happens when you don’t come home.

Remember yelling

Fuck?

Who were you hollering at? Yourself? For crawling out of a stranger’s bed at ten in the morning and straggling back to house and home. Huh! No. Why should you feel guilty, everyone else stays out all night, big deal. It wasn’t like Grace was alone. Danny said he’d stay home with her while you went to your meeting. Said it with a sneer, of course, said it like,

Sure I’ll stay home and look after your kid, because you’re too weak and ineffectual to stay sober on your own

. So. So there. So you met someone who was nice to you, so Steve/Dave (couldn’t get his name straight) with the nice bum, who turned out not to be named Steve or Dave but Karl (of all things), turned out not to be queer either. And not bad in bed either. And furthermore, it was a nice change to be in bed with a man with a decent-size dick who knew what the hell to do with it. And for godsake, who was kidding who, the only reason you and Danny were living in the same house again was for Grace. He was hardly ever around. Wasn’t as if his stony little pea-size heart would be broken over this.

The front door slammed. It was noon exactly.

Hello?

Charlie. What was she doing here? Oh yes, a school day, she must have been out running the streets.

Hello

.

You listened to her denim legs rub toward you. She walked into the kitchen looking like a badger with a bone to pick.

Where the hell have you been?

you asked her.

She squints in the uniform teenage-face-of-disgust.

Where the hell have

I

been? You’re the one wearing the same thing you left in last night

.

How would you know? When’s the last time you deigned to show up in this house?

For your information, I was here last night looking after Grace. Dad had to go out. And you never came home. I looked after Grace, fed her, and put her to bed

.

Oh. Well, that would explain why the place is such a pigsty then

.

Are you for real? You fuckin never came home last night! Where the hell were you—we thought you were dead, but I guess not, eh? Yeah right, an

AA

meeting, you look hungover ify’ ask me. What’d you do, find yourself some poor slob in a bar?

Before you realized, you’d already slapped her face.

How dare you come into this house and talk to me like that, and you of all people—talk about the pot calling the kettle black, the only reason you ever ran away from home in the first place was because you were a horny little slut and you couldn’t keep your pants on to save your —

You stupid whore, don’t ever touch me again. Who —

Shut your mouth, and you’re a goddamn thief too—you think I don’t know you’ve been stealing from me. Well, you’ve got another thing coming, you treat this place like a flophouse, stop by to eat, steal some money, take my pills —

What!—I never took nothing of yours! You’re nuts!

Liar!

Nothings ever gonna change with you, is it? I’m getting the hell out of here—I wish you were dead and I’d take Grace with me. I should take her with me anyway

.

The front door opened and closed, but you were both too furious to shut your mouths.

You just try laying a hand on one hair of that kid’s head and I’ll slit your throat

. And there was a knife in your hand, the butcher knife. Charlie’s eyes were huge and incredulous, brimming hot water. But you meant it, no one was taking the baby anywhere. No. You could feel her in the room somewhere, that door-slam was hers, you could feel her but you couldn’t peel your eyes off Charlie.

Charlie opened her mouth, there was a strand of saliva running between her jaws; she looked about to choke, but words came:

You’re crazy

. That’s all. And she turned to run and then Grace’s

No-o-o Charlie-ee

, and crying and Charlie running for the front door and Grace chasing after, bawling her sister’s name and you squeezed the knife once and let it fall and thunk linoleum and yelled,

Grace, you stay in this house

. But the door opened and the screen door banged in its frame and feet scrambled down wood steps. And there was nothing to do but push palms into eye sockets until the black screen turned psychedelic and you couldn’t hear your own moans. It’s all your fault, you thought again, again, everything’s your fault; he’ll blame you when he comes home. And Grace will hate you for making Charlie disappear again. Can’t change anything, even when you change it. And then you were up and running to the living-room window, terrified she really would take Grace.

They were just a little ways down the sidewalk. Dead leaves scraping cement, scuttling past them onto neighbours’ lawns. The sky was slate and about to pour any minute. You could faintly hear their voices, mostly crying. Charlie shook her head and Grace was hysterical, face blister red, wet with tears and snot and saliva. She threw her arms around Charlie’s waist, pushed her face into Charlie’s stomach, the back of her head covered by Charlie’s hands, hands running over and over silky child-hair, and the both of them stood inside the same square of sidewalk and wailed and mourned for minutes or hours. Charlie’s lips were moving,

She’s crazys

and

I love yous

dropping onto your little one’s head.