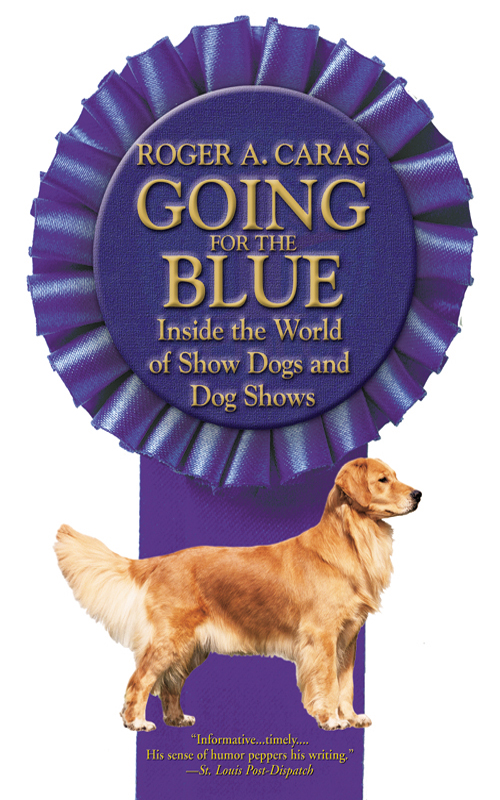

Going for the Blue

GOING FOR THE BLUE

.Copyright © 2001 by Roger A. Caras.All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Warner Books,

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

ISBN: 978-0-7595-2080-6

A hardcover edition of this book was published in 2001 by Warner Books.

First eBook Edition: February 2001

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

T

o my wife, Jill, and our kids, Pamela and Clay—and theirs, Sarah, Joshua, Abaigeal, and Hannah—and Joe and Sheila, son- and

daughter-in-law (we couldn’t have done better if we had picked them ourselves), this book is dedicated. Ours is an expansive clan of dog lovers. We have sixteen canine objects of our affection among us at the moment. (And a parcel of cats and horses,too.) It’s a good start.

A

great many people have contributed to this book simply by talking to me and letting me see and feel their enthusiasm. I am

grateful to each of them, all of them, although the list is too long to spell out here. I have spent my life surrounded by

such people. And their dogs! They have all been my teachers.

Our dogs here on Thistle Hill Farm are, in no particular order, the Greyhounds, Sirius (or Xyerius), Jon-Jon, Lilly, and Hyacinth;

the Basset, Pearl; the Yorkie, Sam; the Whippet, Topi; the Jack Russell Terriers, Olivia and Maude; and the West Highland

White Terriers, Angus and MacGregor. They are all different, each special, without exception, and they offer an incredible

amount of love.

And very special thanks to Robert Taylor and Rhonda Kumm for reading the manuscript and saving me from myself.

Contents

Chapter 1: What Is a Show Dog Supposed to Look Like?

Chapter 2: When It’s Up to the Dog

Chapter 4: There Is a Breed for You

Chapter 6: Trials and Then Some

Chapter 9: Details Worth Noting

T

his book is about dog shows, how they work, what they mean, and how they reflect an incredibly complex relationship, one that

has grown to embrace two very different species of mammals. That relationship has taken thousands of years to develop and

a veritable eternity of evolution.

But before there can be a dog show, the players have to exist and be in place: the dogs and us and, of course, underlying

it all, our wonderful relationship. No question, though, there have to be dogs. All breeds of domestic dogs we know from around

the world belong to just one species:

Canis familiaris

. But their diversity is incredible. A touch of the history of that species, then, but just a touch, will do.

Conventional wisdom, for whatever it might be worth, has caveman (more likely cavewoman, say I) extracting the first or at

least the earliest known dogs from the loins of wolves somewhere between fifteen and twenty thousand years ago. Think of them

as “dawn dogs” intent upon changing our world for us (and they did). Think of them as well as future works of art and important

factors in our health and well-being. The place where the linkup first began to appear has never been identified with certainty,

although it has been pondered and discussed endlessly. There are more experts on this subject than there are on how to play

golf or how to make chili. One of the places that has been suggested is the Middle East, between what are now Israel and India.

In this scenario, the ancestral beast is said to have been a small subspecies of wolf,

Canis lupus pallipes

, a form that is still found in many parts of that mostly arid region. They are rather small—coyote size—and, as I can attest,

noisy at night. When the moon slides across the blue-gray early-night sky of the desert, as the sky itself turns into black

velvet flecked with a billion times a billion stars, out beyond the palm trees that stand now in silhouette, the little wolf,

accused ancestor of all the dogs we know, sings mournfully in a language we can’t understand but in a mood we do understand

all too well, as do the sheep and goats that the wolves covet and stalk. Modern domestic dogs, sleeping outside the tents

in the oasis, lift their heads and answer in their modified voices. Do they understand each other, these dogs and their ancestors?

In some ways they must. They come from the same limb of the same tree in the same corner of the garden.

It is at least possible (not certain, surely, but possible) that the cave dwellers who made this first connection with our

dog ancestors were not even of our species or at least of our exact kind. Perhaps they were Cro-Magnon people, probably, in

part, exterminators of earlier Neanderthal man and the precursors of

Homo sapiens

—us, in other words, or modern man. If some of the extraordinary ages that have been suggested for the emergence of domestic

dogs are even half true, the first dog trainers would have to have been other than our kind. (

Man

, or

he

, as used in this book, does not imply gender but entire species. All of the he/she, him/her constructions I have ever tried

to use ultimately seemed flat, silly, and self-conscious. They would serve no useful purpose here. Let it be said that in

many areas of cultural progress [agriculture, for example, at least in some cultures] women were the leading lights. An interesting

idea: “Old Lady McDonald had a farm . . .” Since we can’t be sure in most cases of the relative participation of the genders

in the inventiveness of our species, we will let it rest.

Man

, as we use it here, is

man

and

woman

, with no prejudice intended.)

Our relationship with our dogs today is probably far different from the form it took in the cave. Such things as style and

aesthetics would not have been very important considerations back then. Little or no energy was spent on cosmetic touches

until quite recently. We can surmise that the cuddle factor was less apparent, but the difference was more on the human’s

part than on the dog’s. It seems fairly certain that cave or dawn dogs, fresh out of their ancestral wolves’ genes, liked

being scratched and petted just as dogs do today. Wolves raised as supposed pets today and intensely socialized do their best

to encourage comfort giving; they are as hedonistic as dogs are. (Wolves, however, are not dogs and they can be bad for your

health. They are not recommended as family pets under any circumstances. Part wolves, wolf-dog hybrids, whatever the wolf

content of their genes, are, if anything, worse. The dog in them has taken away their natural fear of man. That is not good.

It can be lethal or at least disfiguring.)

It has been known for a long time that pet owners who scratch, stroke, or in any way pat their companions have lower blood

pressure and a slower heart rate while they are so engaged. That tends toward longer life and the appearance of children who

are likely to be pet lovers, too. Our pets are good for us. In a sense, they have selectively bred us. I think our collective

ego should be able to handle that.

Very recent studies involved putting heart monitors on dogs. As might be expected, the offer of either food or play cause

a marked increase in heartbeats per minute. When the dogs were petted in any of the usual ways, however, their heart rate

dropped and the animals “cooled out.” We are good for our pets. There has been at the very least fifteen to twenty thousand

years of reciprocity. Neither man nor dog should be alone. We are both pack animals, and, it seems, we were made for each

other.

What this means is that for 150 centuries or more (how much more we may be slow in learning), men and dogs have mutually enjoyed

the sense of touch. It has been good for both of us, and in terms of life span, dog-loving people and people-focused dogs

tend to live longer and create more of their own kind. This hasn’t been by accident; it has been part of the evolution of

both species. It is an integral part of our bond.

Dogs, almost from the beginning, began splitting off into new breeds, none of which from those earliest years are known now.

Just as with so many wild species, dog breeds have become extinct and been replaced by the natural forces of evolution at

work. We think we know some basic breeds from seven to nine thousand years ago—the Ibizan Hound, Saluki, and Samoyed are possible

examples—but we can’t speak with confidence of anything much earlier than that.

A word on the science of it all. When animals are held in captivity and isolated from the wild population of their species,

they will continue to mate, becoming more inbred with each generation. They become, as a group, what is known as a deme. A

phenomenon known as genetic drift comes into play as the captive animals evolve through the same process of natural selection

as any population of their species. But in this case it responds to the opportunities and challenges of the new environment

provided by human beings. Whether we’re aware of it or not at the time, we play a vital role. That is generally true of all

of our domestic animals, about forty-five of them. We create the habitat and provide them with nutrition (or neglect), as

well as frequently creating rigidly controlled mating opportunities. In the case of purebred dogs, we guard that charge jealously.

We are the ultimate matchmakers.

How did early man or preman—Neanderthal, Cro-Magnon, or modern—know the secret of selective breeding? It is unlikely that

cave dwellers 150 centuries ago understood the calendar, the sociology, the chemistry, and the mechanics of their own sexuality.

Sex then was surely essentially opportunistic, often involving migrants who might never come that way again. Today we would

think of much of what happened in and around the cave as rape. Sometimes, three-quarters of a year later, there would be a

baby. Most of the time there would not, for a whole host of reasons. In that kind of hit-and-miss, touch-and-go world, an

understandable connection between act and result was hard to make.

With no knowledge of genetics then, how did cave-living dog fanciers plan selective breeding? They couldn’t—it had to have

come from influences far beyond their imagination or capacity to wonder. Serendipity played a major role. There were a lot

of

oops

and

wows

in procreation eons before genes and the elusive DNA were unmasked.

No animal we know of was domesticated by early man unless that animal was already locked into a relationship with man. There

had to be a link, and it took the form of hunting. Man hunted many species for meat and pelts—almost everything around him,

in fact, and the wolf was on the hit list. If a band of hunters whooping, hollering, and brandishing flaming torches and throwing

rocks neutralized a pair of adult wolves, they frequently ended up with a litter of cubs to show for their efforts. Without

refrigeration they learned soon enough not to kill more cubs than they could eat right away, or the surplus would become rancid

and make them ill. Dead and rotting meat could make even a cave dwelling far worse than it had to be. A better idea was to

keep the cubs alive in a corner of the cave until they were needed for the pot. (Actually, Paleolithic man and his precursors

didn’t have pottery. Sad to contemplate, but those first evolving dog fanciers probably roasted wolf cubs the way we do marshmallows.)

Since humans are born quite thoroughly helpless, we have a years-long tutorial period. To accommodate this species characteristic,

our mothers fulfill the nurturing role. Given a nurturing mother with or without her own baby in hand, add a litter of squirming

and squealing wolf babies, all of which display endearing characteristics, and we were on our way to dogdom. That route, given

the human capacity for pride and competitiveness, led inexorably to formalized dog shows in England in the middle of the nineteenth

century. It was slow in coming but it was foreordained.

The first endearing characteristic that caveman serendipitously selected for was gentleness. The roughnecks, the biters in

the crowd, were undoubtedly the first onto the barbecue. It was perfectly natural to opt for easy keepers, and early man almost

surely did exactly that, although ignorant of the significance of what he was doing. If a dweller in cave A had a male easy

keeper and the folks in cave B had a female with the same kind of disposition, the stage was set. The cubs grew, they interacted

as juveniles, they mated, and a breed characteristic—relative gentleness—was intensified dog generation by dog generation.

With gestation a brief sixty-three days and sexual maturity under a year, things would have moved along smartly. It is interesting

that we still look for that in our dogs today, a certain softness.