Goodbye, Darkness (37 page)

At the end of a day's movements, no matter how weary you were, you dug a foxhole, usually with a buddy. I struck big rocks and thick roots with discouraging frequency, but I never broke out my canned C rations (usually beans) or boxed K rations (cheese, crackers, ersatz lemonade powder, and “Fleetwood” cigarettes, a brand never heard of before or since) until I had a good hole. There was no hot food if you were on the line; fires were naturally forbidden there. Most of us carried cigarette lighters made by the Zippo Manufacturing Company of Bradford, Pennsylvania; before the war they had been nickel-plated and shiny, but now they were black with a rough finish, and if you were careful you could light a butt without drawing fire. Sometimes you could get away with heating soup or coffee in a canteen cup over a “hot box,” a square of paraffin. But the cups were a problem. Their rolled-over rims collected so much heat that they burned your lips, so you had to wait until the contents were tepid. On the line you were seldom hungry, yet few escaped diarrhea.

Bon appétit.

At night you kept watch-on-watch in two-man foxholes — four hours alert, four hours of sleep. When your turn to watch came you lay huddled in the darkness, listening to the distant rumblings of armored vehicles, straining to hear counterattack giveaways: the whiplike crack and shrill hissing of streams of sleeting small-arms red-tracer fire, the iron ring of ricochets, and the steady belch of automatic fire. Now and then a parachute flare would burst overhead, and you could see the saffron puffs of artillery in the ghostly light. It was a weird, humiliating, primitive life, unlike anything in my upbringing except, perhaps, the stories of Jules Verne. You learned to explore the possibilities of the few implements you had, and some discoveries were ingenious; behind the front, in reserve, you could use your steel helmet for digging, cooking, bathing, and, in the jungle, for gathering fruit. But it would be wrong to infer that the cheerful foot soldier solved all his wretched little problems. For example, if rain was falling, which it seemed to be most of the time, you were fully exposed to it, and helpless in deluges. By the time you had a hole dug, a couple of inches of rain had already gathered in it. Tossing shrubs in didn't help; their branches jabbed you. You wrapped yourself in your poncho or shelter half, but the water always seeped through. You lapsed into a coma of exhaustion and wakened in a drippy, misty dawn with your head fuzzy and a terrible taste in your mouth, resembling, Rip once said, “a Greek wrestler's jockstrap.” Then, like any other worker tooling up for the day, you went about your morning chores, making sure that machine gunners were covered by BAR men, that the communications wire strung along the ground last night was intact, that the riflemen had clear fields of fire and the flanks were anchored and secure.

The Marine in a line company earned a very hard dollar. Unless be became a casualty, lost his mind, or shot himself in the foot — a court-martial offense — he stayed on the line until he was relieved, which usually happened only when his outfit had lost too many men to jump off in a new attack. Behind the lines his unit absorbed replacements (who always got a chilly reception; they were taking the places of beloved buddies) or attended to details which had to be postponed in combat. Some of these could be grueling. Once, my jaw throbbing with an impacted wisdom tooth, I hitchhiked back to a dentist's tent. There was no anesthetic. Lacking electricity, the dentist powered his drill by pumping on an old-fashioned treadle with his right foot. He split the tooth into three pieces and succeeded in extracting the last of them only after I had been in his chair six hours. Luckily, when I got back to the section I found the guys had scrounged some jungle juice produced by the Seventh Marines. The Seventh had built a Rube Goldberg still with old brass shell casings and copper tubing from wrecked planes, and sometimes ladled out a canteen cup of the result to sick outsiders, which, God knows, included me. Lieutenants fresh from Quantico tried to close the still down, but experienced officers called them off. In combat minor infractions were overlooked. Once the Raggedy Ass Marines even enlisted Colonel Krank as an accessory after the fact in a conspiracy against the Army Quartermaster Corps. Discovering that GIs had all been issued new combat boots, which could be quickly strapped on, while we still wore the old prewar lace-up leggings, Rip and Izzy plotted a raid. Acquiring an army requisition form from a sympathetic black corporal, they drew up a directive for the issuance of fifty pairs of boots and took it to the quartermaster dump. They were wearing the thin windbreakers which then passed for field jackets; there was nothing to indicate that they were Marines or identify their ranks. Rip represented himself as a first lieutenant; Izzy said he was a sergeant. When the NCO at the dump hesitated, Izzy took him aside and warned him that too much fighting had made the lieutenant trigger-happy; if they didn't get the boots fast, somebody might get shot. So they got the boots. Before they drove off in a liberated jeep, Izzy, in the finest tradition of the Raggedy Ass Marines, left his spoor, countersigning the requisition “Platoon Sergeant John Smith.” Since there were no platoon sergeants in the army, within a few hours angry army officers realized what had happened and demanded that the Marine Corps produce the thieves. You can't hide fifty pairs of combat boots in a cramped reserve area. Krank knew exactly what had happened. The price for his silence was one pair for himself.

Izzy and Rip were heroes, not so much for their loot as for their triumph over “the rear echelon.” It is a blunt statistic that for every man who saw action during the war, nineteen men, out of danger, were backing him up. But in practice “rear echelon” was the most relative of phrases. Your definition of it depended on your own role in the war. To the intelligence man out on patrol near the Jap wire, the platoon CP was rear echelon; to the platoon it was the company CP; to the company it was the battalion CP; to the battalion it was the regimental CP; to the regiment it was the divisional CP, and so on, until you reached the PX men who landed at D-plus-60 and scorned the “rear echelon” back in the States. The term was sensitive and was often misunderstood by civilians. Bing Crosby told reporters that it was the morale of the gloomy rear echelon troops which needed boosting; up on the line, he said, “morale is sky-high, clothes are cleaner, and salutes really snap.” Of course, Crosby hadn't been near the front; virtually no USO shows and Red Cross girls reached us up there, uniforms were filthy, and any rifleman who saluted an officer on the line, targeting him for an enemy sniper, would have been in deep trouble. The men there would have settled for a Coleman stove and a hot-mess line, but the greatest contribution to their spirits, plus or minus, was mail call. Once the adjutant had been left with the tragic problem of letters whose addressees had been killed in action, individual Marines wandered off alone to read and reread every line from home. Usually they returned looking brighter, though there were exceptions. Some of their correspondents were unbelievably stupid. They complained about gas shortages, or rationing points, or income taxes, or problems with their Victory gardens — this to men who would have swapped places with them under almost any terms. The mail call I remember best came at Christmas, 1944. Pip got a present from his mother in Indianapolis. We all hovered over him when he unwrapped it. It was a can of Spam.

To us the dividing line between the front and the rear echelon was measured by the range of enemy artillery, which, for Japanese 150-millimeter guns, could be 21,800 yards, their maximum, though they had a 24-centimeter railway gun which could throw a shell 54,500 yards. Ordinarily you were relatively safe if you were two miles from Nip batteries. Inside that perimeter, however, you knew you could be hit at any time, and you developed a professional interest in all enemy weapons. During a crashing barrage, with Jap artillery raging and thundering all over the horizon, with as many as a dozen enemy shells (incoming mail) overhead at one time, you hugged the ground, which began to tremble when American guns (outgoing mail) replied. Under close, flat fire the projectiles whipping in were no more identifiable to the veteran than to the greenest replacement. But most of the time you had some warning, and you became familiar with the acoustics of the big cannon. Given a little time in combat — the first days were dangerous for the newcomers — you could sort out the whines of 75-millimeter, 105-millimeter, 24-centimeter, and 30-centimeter howitzers; coastal guns as large as 8-inchers (203 millimeters); 120- and 150-millimeter siege guns; rocket bombs; and huge, bloodcurdling 320-millimeter mortars.

Some shells moaned. Some chug-chug-chugged like a laboring locomotive. Some knocked rhythmically. Others chirred loudly throughout their flight, or rustled tonelessly, or sounded like a stick being jerked through water. There were shells that fizzled like sparklers, or whinnied, or squealed, or whickered, or whistled, or whuffed like a winter gale slamming a barn. The same principle governed all these sounds: the projectile's blast created a vacuum into which air rushed. But various sizes, shapes, and trajectories produced different effects. Howitzers had a two-toned murmur. HE (high-explosive) and phosphorus shells came with a whispering whoosh. Flat-trajectory mail was delivered with a noise like rapidly ripped canvas, and if fired at close range it neither whistled nor whined; it just went

whiz-bang.

There were those who preferred flat-trajectory fire, because if it missed you it kept right on going, leaving only the echo of its

yeeeooowww.

Those who favored howitzers and mortars argued that since they lobbed their mail in, you had a few moments' notice. The bad news was that if one missed you by ten yards it could still kill you. Eventually you reacted intuitively, knowing that you could never achieve complete mastery of the subject: there were shells that warbled after they exploded, shells that warbled and never exploded, shells that exploded without any warble at all.

If a shell landed within a hundred yards you had about one second to hit the deck. There were some Marines who affected indifference to mortars bursting nearby. This was usually a symptom of inner despair, of the terrible need to show contempt toward inhuman missiles which were so contemptuous of them. But it was foolish; even tiny fragments from a shell were white-hot and could kill you. And shrapnel could create new perils from harmless stone. On Okinawa General Simon B. Buckner, the American commander, was standing beneath a granite bluff when a Jap projectile hit the cliff. Buckner got a piece of rock and it killed him. I usually treated ominous sounds in the sky with great respect. Once I even dove into a slit trench — a latrine — to escape a 105-millimeter shell homing in on me. Nobody approached me for several hours, but I didn't apologize. Arriving mail always turned my joints to jellied consommé. The fear continued after the war; the sudden zip of a heavy zipper made me jump for a year after I discarded my uniform, and it was late in the 1940s before I could walk near New York's old Third Avenue El without trembling.

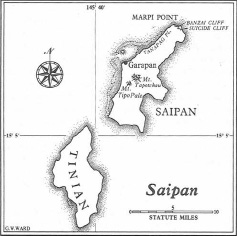

Such was our trade and our Stone Age life: knowing our weapons and how to use them, knowing the enemy's weapons and trying to avoid them, bitching about those behind our lines who didn't have to fight, dreaming of home, fantasizing about girls, controlling our terror, bathing when we could, if only in a water-filled shell hole, and blessing the corpsmen with their morphine syringes, plasma, and guts in risking death to bring back the wounded. Our vision of the war was largely tunnel vision. To each of us the most important place in the world was his foxhole. The impact of MacArthur's and Nimitz's twin offensives was lost on us. Most Marines were as ignorant of Pacific geography as their families at home. Yet it would be wrong to infer that they were wholly ignorant of strategy and tactics. They knew, as even wild animals know, the tactical advantages of deception and surprise. The value of the information brought back by the Raggedy Asses' reconnaissance patrols was obvious. More or less by instinct every fighting man in the Corps came to understand the advantage of attacking troops, who could pick the time and place of assault, and the defenders' advantage, that of fortifying likely targets. Some men even grasped the evolution of amphibious warfare, a combination of strategic offense and tactical defense — once a beachhead had been taken, the invaders could form a perimeter and await the Jap counterattacks. Success in amphibious offensives clearly turned on coordination. Everyone knew when synchronization went wrong. It had happened on Tarawa. It happened again on Saipan.

At dawn on June 13, 1944, as President Roosevelt prepared to run for a fourth term, the mightiest fleet in history till then steamed into the Philippine Sea: 112 U.S. warships, led by 7 battleships and 15 flattops carrying nearly a thousand warplanes. In their midst were 423 transports and freighters bearing 127,571 fighting men: the Second, Third, and Fourth Marine divisions, the First Provisional Marine Brigade, and the Twenty-seventh Army Division. The overall commander was a Marine general, Holland “Howling Mad” Smith. The commander of the Twenty-seventh Division was an army general, Ralph Smith. (The two Smiths cannot be confused, as we shall see.) The task force's mission was the capture of the three great Marianas islands — Guam, Saipan, and Tinian — each almost completely encircled by coral reefs. The prize was to be Guam, with its magnificent anchorage and many airstrips, but Saipan was to be seized first. Saipan was closer to Tokyo and therefore a better base for the new B-29 Superfortresses, which, using Aslito air base, at the southern end of the island, could fly daily raids over Tokyo. Tinian, lightly defended, would fall almost of its own weight. Meanwhile, three days after the landing on Saipan, the Marines were scheduled to hit Guam. Actually they didn't wade ashore on Guam until over a month later. Saipan, like Tarawa — like all the Marine battles which were to follow — was far tougher than anyone had expected.