Gracefully Insane (24 page)

Authors: Alex Beam

In the spring of 1969, conflicting commitments started pulling Sexton

away from the McLean seminar. She taught her last class in June. She corresponded with several of the patients for a few years after the class. Although she eventually lost touch with them, several followed her high-profile career in the newspapers and magazines.

away from the McLean seminar. She taught her last class in June. She corresponded with several of the patients for a few years after the class. Although she eventually lost touch with them, several followed her high-profile career in the newspapers and magazines.

Perhaps inevitably, the intensely self-critical and depressive Sexton viewed the seminar as a failure. In December 1973, she gathered

some of the McLean poems and notes into a manila folder and scrawled a note in felt-tipped pen on the outside cover: “First teachings of creative writing—1969 (very difficult due to my insufficient knowledge of handling groups and the fact that the group was constantly changing and the aides were easily mixed up with the poets—Decide more commitment on the part of the poet is needed for me to be able to teach well.”)

some of the McLean poems and notes into a manila folder and scrawled a note in felt-tipped pen on the outside cover: “First teachings of creative writing—1969 (very difficult due to my insufficient knowledge of handling groups and the fact that the group was constantly changing and the aides were easily mixed up with the poets—Decide more commitment on the part of the poet is needed for me to be able to teach well.”)

Whatever her misgivings, the McLean seminars did give Sexton the confidence to press forward with teaching. One of the McLean students organized a weekly seminar for his Boston-area Oberlin classmates at Sexton’s home. Then Sexton arranged a faculty appointment at Boston University, where, in the 1970s, her poetry seminars achieved the same mythic cachet accorded to Lowell’s classes in the 1960s.

The McLean students seemed to love Sexton, for her celebrity, for her own struggles with mental illness, and for the effort she invested in the course. Margaret Ball, who sent Sexton periodic updates on the patients’ lives between the seminars, informed her more than once that her works were stolen more than any other author’s: “‘All My Pretty Ones’ (replacement volume 4) lasted 1 week on the shelf before stolen.... It’s their highest compliment, because usually they’re so honest.”

Robert Perkins, who remembers Sexton as “very pretty and very nervous,” wrote that “I’ve since come to appreciate how difficult it must have been for Anne Sexton to come back to the hospital and deal with a group of loonies. She had been there herself. Maybe she felt she could help one of us. Maybe she did.”

In 1973, Sexton’s awful wish was finally granted in full; she was admitted

to McLean as a patient for five days of psychiatric examination. The grim “Patients’ Property Form” is one of the few documents remaining from this visit, detailing that Sexton surrendered her

nine credit cards—one from the Algonquin Hotel—and $220 in cash and traveler’s checks ($5 in dimes, presumably for parking meters) on August 2 and reclaimed her effects on August 7.

to McLean as a patient for five days of psychiatric examination. The grim “Patients’ Property Form” is one of the few documents remaining from this visit, detailing that Sexton surrendered her

nine credit cards—one from the Algonquin Hotel—and $220 in cash and traveler’s checks ($5 in dimes, presumably for parking meters) on August 2 and reclaimed her effects on August 7.

Sexton’s former student Eleanor Morris met her teacher unexpectedly in the North Belknap medium-security hall. “She remembered me from the seminar, but we didn’t talk much,” Morris recalls. “She looked so awful.... my heart went out to her.” Here was the terrible leveling of mental illness; Sexton, the elegant, chain-smoking, Pulitzer Prize winner cast adrift among her student-patients on the desperate ocean of unhappiness. Sexton was just one year away from her own suicide, firmly embarked upon her

Awful Rowing Towards God,

the title of her last collection of poems.

Awful Rowing Towards God,

the title of her last collection of poems.

Morris still remembers her clock radio waking her on Saturday, October 5, 1974. A newsreader announced that the poet Anne Sexton had died. “It just said she had died, but I knew she had committed suicide, and I spent the whole morning crying,” Morris says.

Morris still has a copy of a book of poems that Sexton gave her after one of the seminars, a 1966 collection called

Live or Die.

In the flyleaf, Sexton wrote: “My directive is LIVE—to Ellie.”

Live or Die.

In the flyleaf, Sexton wrote: “My directive is LIVE—to Ellie.”

Eleanor Morris is living and writing poetry in Concord, Massachusetts.

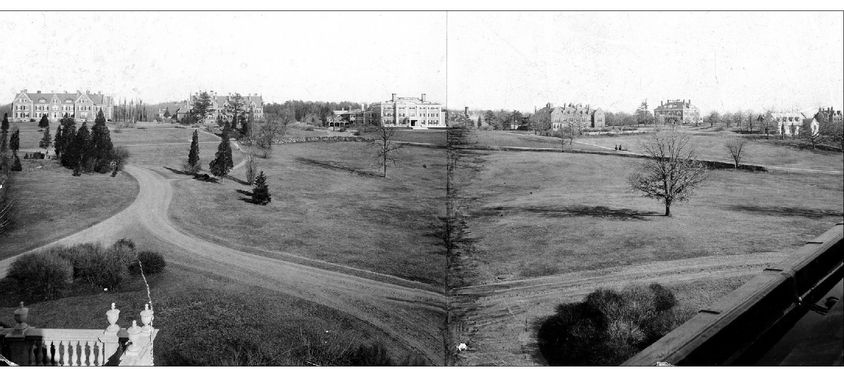

Views of the McLean Hospital grounds, 1900.

Credit:

McLean Hospital.

McLean Hospital.

In these pictures taken during the late 1930s and early 1940s, nurses and aides skate on the “Bowl,” a concave expanse of lawn in front of the administration building; ski in the woods surrounding the hospital; and play croquet, tennis, and golf. Patients took part in these activities though they were never photographed for reasons of privacy.

Credit:

McLean Hospital.

McLean Hospital.

Horse and carriage, used to take patients on outings and visits, 1920.

Credit:

McLean Hospital.

McLean Hospital.

Other books

Owned by the Russian Mafia Boss: A Mob Romance by Rose, Bella, Lee, Leona

Homecoming Hero by Renee Ryan

Time Shall Reap by Doris Davidson

This Changes Everything by Swank, Denise Grover

What If Ireland Defaults? by Brian Lucey

A Night at Club Vampire 2 by elixaeverett

Roger Sheringham and the Vane Mystery by Anthony Berkeley

Fairy Tale by Cyn Balog

His Favorite Girl by Steph Sweeney

The History of Love by Nicole Krauss