Gracefully Insane (25 page)

Authors: Alex Beam

A hydriatic suite where nurses and aides administered the many different forms of hydrotherapy.

Credit:

McLean Hospital.

McLean Hospital.

A photo of the McLean medical staff in 1945. Director Franklin Wood stands in the front row, center, in a gray suit wearing his trademark red carnation. At his right is psychiatrist-in-chief Kenneth Tillotson, who later became embroiled in an opéra bouffe sex scandal involving a McLean nurse.

Credit:

McLean Hospital.

McLean Hospital.

The star-crossed couple Stanley and Katharine McCormick, on their wedding day, in 1904, in Switzerland. Stanley, an heir to the International Harvester fortune, lived at McLean for two years and eventually moved his doctors and nurses west to a family estate in Santa Barbara.

Credit:

State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

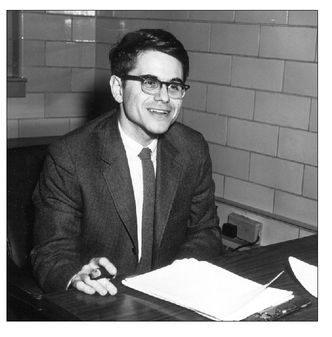

Dr. Harvey Shein, the brilliant young director of residency training whose suicide traumatized the hospital in 1974.

Credit:

McLean Hospital.

McLean Hospital.

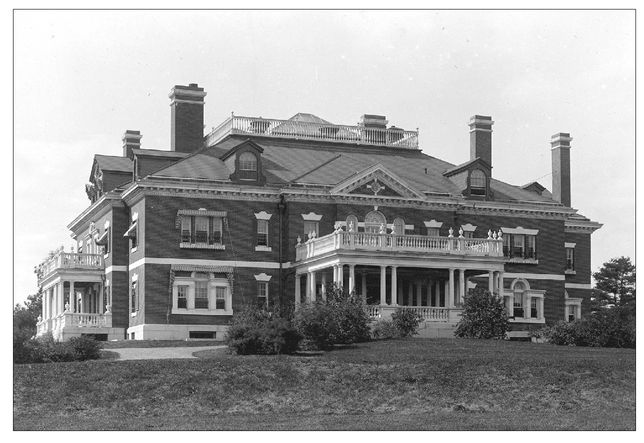

Louis Agassiz Shaw II, the wealthy society “novelist” who never stood trial for strangling his maid at his mansion in 1964. Instead, his lawyer won him a lifetime of luxurious living at McLean.

Credit: Boston Globe.

An inventory map of hospital flora created by two patients in the mid-1960s. Copies still hang in many offices throughout the hospital.

Upham Memorial Hall, the magnificent “Harvard Club” of McLean. At one time, Harvard graduates supposedly occupied each of its sumptuous corner suites.

Credit:

McLean Hospital.

McLean Hospital.

9

Staying On

THE ELDERS FROM

PLANET UPHAM

PLANET UPHAM

Dr. Stephen Washburn

P

sychiatrists hardly ever use the word “cure.” They try to help pa

tients, many of whom become “clear,” successfully freeing their minds from the shackles of anxiety, depression, or more severe mental illness. But the profession’s wellness model is like that of oncology. To be cancer-free or mentally healthy is to be in the happy state of remission. But many patients never get there. Some

patients never improve or improve only marginally, and in the McLean of the not-too-distant past, that meant they never left the hospital.

sychiatrists hardly ever use the word “cure.” They try to help pa

tients, many of whom become “clear,” successfully freeing their minds from the shackles of anxiety, depression, or more severe mental illness. But the profession’s wellness model is like that of oncology. To be cancer-free or mentally healthy is to be in the happy state of remission. But many patients never get there. Some

patients never improve or improve only marginally, and in the McLean of the not-too-distant past, that meant they never left the hospital.

A young female social worker who worked in McLean’s children’s program during the 1980s told me about a group of particularly old patients whom the children called the “elders.” Ageless, wraithlike, oddly spectral, they were both scary to the children and also objects of infant mockery. They were quite literally a dying breed. They lived in the old style, in comfortably furnished single rooms. They had bookcases, attractive bedspreads, and furniture brought from home. Of course, they

were

home. Some of them had called McLean home for decades.

were

home. Some of them had called McLean home for decades.

One of the white-haired old men was Louis Agassiz Shaw, a venerable Brahmin who had spent more than twenty years at McLean and was soon to be shipped off to a North Shore nursing home to die. A descendant of both Robert Gould Shaw, the heroic Civil War captain played by Matthew Broderick in the movie

Glory,

and of Louis Agassiz, the Swiss-born Harvard zoologist who revolutionized the study of biology, Shaw started off in the right direction.

19

He attended Noble and Greenough School, where he made his mark as a student poet. From Nobles, as it is called, Shaw proceeded to Harvard, where he joined the Porcellian Club, a watering hole for aristocratic “legacies”: boys whose

fathers and often grandfathers and beyond had attended the college. In his senior year, 1929, Shaw published a novel,

Pavement,

under the pen name Louis Second. (His full name was Louis Agassiz Shaw II.) The book is almost unreadable and was probably printed at Louis’s expense; there is no trace of it in the

Literary Digest,

which reviewed most novels of the time.

20

Ten years after graduating, and at five year intervals afterwards, Shaw dutifully, if laconically, reported to his Harvard classmates on his activities: “Engaged in writing for various publications and anthologies. ... on office staff of Citizens’ Committee of U.S.O. ... member, St. Botolph, Somerset and Myopia Hunt Clubs.” He often rode to Myopia, an exclusive polo club, along bridle paths that linked his fifteen-room Topsfield mansion with the club and with the neighboring estate of General George Patton. Twenty-five years out of college, he had little to show for himself, especially when compared with Harvard graduates climbing the ladders of business, government, and the arts.

Glory,

and of Louis Agassiz, the Swiss-born Harvard zoologist who revolutionized the study of biology, Shaw started off in the right direction.

19

He attended Noble and Greenough School, where he made his mark as a student poet. From Nobles, as it is called, Shaw proceeded to Harvard, where he joined the Porcellian Club, a watering hole for aristocratic “legacies”: boys whose

fathers and often grandfathers and beyond had attended the college. In his senior year, 1929, Shaw published a novel,

Pavement,

under the pen name Louis Second. (His full name was Louis Agassiz Shaw II.) The book is almost unreadable and was probably printed at Louis’s expense; there is no trace of it in the

Literary Digest,

which reviewed most novels of the time.

20

Ten years after graduating, and at five year intervals afterwards, Shaw dutifully, if laconically, reported to his Harvard classmates on his activities: “Engaged in writing for various publications and anthologies. ... on office staff of Citizens’ Committee of U.S.O. ... member, St. Botolph, Somerset and Myopia Hunt Clubs.” He often rode to Myopia, an exclusive polo club, along bridle paths that linked his fifteen-room Topsfield mansion with the club and with the neighboring estate of General George Patton. Twenty-five years out of college, he had little to show for himself, especially when compared with Harvard graduates climbing the ladders of business, government, and the arts.

Louis had two distinguishing characteristics: He was eccentric, and he was a snob. In the entrance hall to his mansion, Shaw used a plaster cast of his own foot to collect visitors’ calling cards instead of the customary silver tray. He also kept a copy of the Social Register next to his telephone and instructed domestics not to accept calls from men and women not listed there. When Shaw had his house painted, he insisted that the workmen place large metal trays under their scaffolding to ensure that no drips or scrapings fell into his garden. He arranged for frequent and costly repairs to the mansion and always waited a year before paying the “tradesmen.” A Nobles classmate, the landscape architect Sidney Nichols Shurcliff, recalls that Louis publicly humiliated him for

accepting a glass of cool lemonade from Louis’s maid in the servants’ quarters one scorching summer day.

accepting a glass of cool lemonade from Louis’s maid in the servants’ quarters one scorching summer day.

Moving into his fifties, Louis was leading the not altogether unusual life of the educated, ineffectual, Boston twit. He rode to the hunt. He appeared at his clubs. In the Thirty-fifth Anniversary Report to his Harvard classmates, he provided no details of his life other than his home address in Topsfield, Massachusetts—incorrectly, as it turned out. In fact, he had taken up residence at McLean Hospital.

Shaw was in McLean because he had killed someone. “Cousin Louis did something that was highly inappropriate,” is how his relative Parkman “Parky” Shaw, a longtime pillar of the Beacon Hill Civic Association, put it to me. When we first discussed Louis, Parkman and I experienced a classic Boston misunderstanding. “He’s the one in the Robert Lowell poem,” I said, meaning that Louis was clearly “Bobbie, Porcellian ’29” in the famous poem “Waking in the Blue.” “No, that’s

Robert Gould

Shaw,” Parkman corrected me. But we were talking about different Lowell poems; Parkman meant Lowell’s memorably dispiriting “For the Union Dead,” which evokes the bitter sacrifice of Robert Shaw’s “bell-cheeked Negro infantry” parading across the Boston Common just two months before their bodies, and Shaw’s, would be tossed into a mass grave after their suicidal attack on Fort Wagner, South Carolina. Once we cleared that up, we moved on to discuss Louis’s “highly inappropriate” action: He had strangled his fifty-six-year-old Irish maid, Delia Holland, one night inside his sprawling mansion. According to the newspapers, Louis told police that Holland had been planning to kill

him

by turning on “secret gas jets” in his bedroom. Here is an account by the arresting officer, David Moran, of Louis’s last night of freedom:

Robert Gould

Shaw,” Parkman corrected me. But we were talking about different Lowell poems; Parkman meant Lowell’s memorably dispiriting “For the Union Dead,” which evokes the bitter sacrifice of Robert Shaw’s “bell-cheeked Negro infantry” parading across the Boston Common just two months before their bodies, and Shaw’s, would be tossed into a mass grave after their suicidal attack on Fort Wagner, South Carolina. Once we cleared that up, we moved on to discuss Louis’s “highly inappropriate” action: He had strangled his fifty-six-year-old Irish maid, Delia Holland, one night inside his sprawling mansion. According to the newspapers, Louis told police that Holland had been planning to kill

him

by turning on “secret gas jets” in his bedroom. Here is an account by the arresting officer, David Moran, of Louis’s last night of freedom:

I pushed through the second door.... the room was a library. Stacks of books wall-to-wall and floor-to-ceiling. Books.

And a man in an armchair staring at me.

At the opposite end of the room was a fiftyish guy seated calmly in a stuffed chair. I figured it had to be the owner, Shaw. Amazingly, he showed no observable reaction to a state trooper stalking into his study with a long-barreled thirty-eight for a calling card. What bothered me even more was his calm demeanor when a dead body lay outside his door....

I leveled my gun on him. It wouldn’t have taken too belligerent a move under the [lap robe that Louis was wearing] for me to react. Finally, he acknowledged my arrival. But his look was as if I’d just tracked mud on his Persian carpet.

“And just who might you be?” His tone suggested that I’d also interrupted his morning meditation.

“State Police,” I responded automatically. Taking a long shot, I blurted, “Why’d you kill her?”

“She was bothering me. Made too much noise!” he answered sedately. “I

told

her to stop.”

told

her to stop.”

Other books

The - Cowboy’s - Secret - Twins by Dilesh

Treasures of Time by Penelope Lively

Demon Singer by Nichols, Benjamin

Cardinal by Sara Mack

Days of High Adventure by Kay, Elliott

Nero's Fiddle by A. W. Exley

Die Like a Dog by Gwen Moffat

Fallen (Chronicles Of The Fallen) by Morgan, Julie

Balancing It All: My Story of Juggling Priorities and Purpose by Bure, Candace, Wilkerson, Dana

Night Fever (A Rue Darrow Novel Book 3) by Audrey Claire