Greece, the Hidden Centuries: Turkish Rule From the Fall of Constantinople to Greek Independence (5 page)

Authors: David Brewer

Tags: #History / Ancient

John VI determined on decisive action, and this ushered in the third phase. He appointed his son Manuel as the first so-called Despot of the Morea, with a free hand to take all necessary measures. Manuel and his successors as despot were successful in imposing some order internally but were still at the mercy of intervention from outside, principally from the Turks. The last two despots ruled jointly, but uneasily, Thomas Palaiologos having the north-west half and his brother Dimitrios the south-east, including Mistrás, the long-term seat of government.

Despite the turmoil that the Peloponnese had suffered ever since the establishment of Mistrás in 1249, Mistrás had continued to be a cultural and intellectual centre. Its most distinguished citizen was Georgios Yemistós Plíthon, neo-Platonist philosopher, political theorist and friend of the future patriarch Yennádhios. Plíthon came to Mistrás from Constantinople in 1407 and remained there till his death in 1452, a witness to the last turbulent years of the Byzantine despots in the Peloponnese though not, by a year, to the end of the Byzantine Empire. It was neither the first nor the last period of history in which culture flourished while every other mark of civilisation was collapsing around it. In 1460, seven years after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks, the whole Peloponnese, except for Monemvasía and the Venetian towns, was conquered by Turkish forces and became a province of the Ottoman Empire.

The constant upheavals that plagued the Peloponnese between 1204 and the arrival of the Turks were replicated in the rest of the country. The Duchy of Athens in central Greece was under constant attack from neighbours or newcomers seeking to acquire territory. At the start of the fourteenth century the Catalan Grand Army, a force of mercenaries hired by the Byzantines, which was grand only in that it was formidable,

arrived in Greece. In 1311, after a decisive battle, the Catalans seized control of the Duchy of Athens. Their methods were so appalling, even by the standards of the day, that the Pope excommunicated them as ‘these senseless sons of damnation’.

19

The Catalans gave way to the Acciauoli, originally a banking family in Naples who turned to politics and war, and who captured the Athens Akropolis in 1388. In 1456 they too yielded their possessions to the Turks.

In the north the two separate provinces, Ípiros and Thessalonika, were unified under the Byzantines after 1259, giving the combined territory access to the sea on both east and west along the old Roman Via Egnatia. Thessalonika, with its fine harbour and its position on the Via Egnatia, was the biggest commercial prize in Greece. It was besieged by the Catalans in 1308, governed by a chaotic commune in the 1340s at the time of the Black Death, occupied by the Turks for ten years at the end of the century, recovered by the Byzantines, ceded by them to Venice in 1423 in a vain bid for survival, and finally taken by the Turks in 1430.

The rule of the crusaders and their successors in Greece has been described as ‘a unique experiment in the conquest and settlement of lands which possessed their own rich cultural heritage’.

20

To call it an experiment is somewhat surprising. The Franks were not experimenting in the sense that they were trying a variety of solutions to their problems to see which worked best. They were imposing on their new territories the only system they knew: acquisition by war or by dynastic marriage, control by occupying or building fortresses, and exploitation by a feudal system similar to that in their homelands. For many and perhaps most Greeks, Frankish rule was in many ways like the Byzantine rule that had preceded it. With the arrival of the Turks another alien rule was imposed on Greece, one deriving from a different religion-based philosophy but as before not a complete break with the past. And Turkish rule brought, if nothing else, stability to the lands of Greece that had been fought over by competing forces for the previous two centuries.

2

1453 – The Fall of Constantinople

T

he fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453 was not the start of Turkish presence in Greece. Far from it. Turkish raids in the Aegean are recorded as early as 1303, and in the following decades Turkish ships attacked the islands of Santoríni, Kárpathos, Éyina, and Évia. On the mainland they raided towns opposite Évia and in the north-east Peloponnese. The raiders were flotillas of individual corsairs, and their object was to take slaves: 20,000, it is said, in a single raid on Évia. Only the Venetians were powerful enough to challenge the Turks at sea, and Venice became in effect the protecting power of Greece against the Turkish corsairs.

By 1361 the Turks were on the threshold of today’s Greece, having captured Adrianopolis, modern Edirne, within five miles of the present Greek–Turkish border. This otherwise insignificant town has the distinction of being the most frequently contested place in the world because of its position at the European end of the Europe–Asia land bridge. It has been fought over whenever military forces have moved from west to east, as the Romans did, or east to west as the Turks had now done. By one reckoning Edirne has been the scene of fifteen major battles or sieges over the centuries, of which the Turkish capture of 1361 was the twelfth. A few years later Edirne became the capital of the Ottoman Empire.

From Edirne the Turks moved west and then south through Greece. In 1391 they took Thessalonika from the Byzantines after a four-year siege. They then advanced south through Thessaly, capturing major towns, and within a few years were masters of Sálona, modern Ámphissa, and Livadhiá, only a few miles north of the Gulf of Corinth. Then came a check to Ottoman expansion. In 1402 the Turks were heavily defeated at Ankara by the forces of Tamerlane, and the Sultan was taken prisoner. In the next year the Byzantines recovered Thessalonika from the Turks, but the Turks took it again in 1430, and thereafter held it for nearly five centuries.

The Turks were now established in most of Greece, and indeed most of the Balkans. The lands of today’s Bulgaria and Romania, as well as

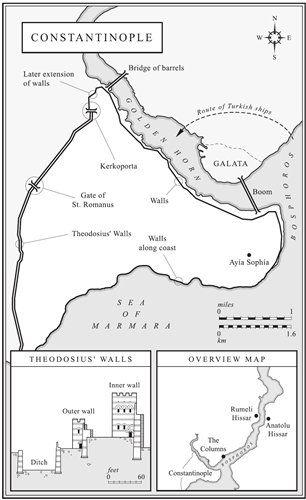

Albania, Bosnia and Serbia, were all Turkish vassal states, acknowledging Turkish supremacy and paying tribute. But the final bastion of the now shrunken Byzantine Empire remained unsubdued: Constantinople itself. The Turks had tried unsuccessfully to take the city in a seven-year siege in the 1390s, and again in 1422. In the spring of 1453 Turkish forces appeared again outside the walls of Constantinople, the last barrier, symbolic as well as actual, to the total Ottoman domination of south-east Europe.

The Sultan commanding the Turkish forces was Mehmed II, later to be known as the Conqueror. He had first come to the throne in 1444 when he was perhaps as young as twelve, his father Murad II having abdicated in his favour. But within months his father was recalled to lead the Turks against a threatening army of Hungarians, Poles and Venetians, a command that the boy Mehmed was considered incapable of exercising. Two years later his father returned to the throne, an ignominious demotion for Mehmed. In 1451, on his father’s death, Mehmed again became Sultan, now a young man with something to prove.

There could be no better proof of his abilities than the capture of Constantinople. In the last half-century two of his predecessors, one of them his father, had tried and failed. There were good reasons for bringing Constantinople under Turkish control: as long as Constantinople remained a Christian city it was a possible focus for a new crusade against the Turks, and possession of Constantinople would give the Turks control of all trade between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. There was a third but less obvious reason: the Turks had formidable land forces but no war fleet, only an assembly of individual corsairs. Constantinople would provide both ship-building facilities and a secure naval base, protected by the narrows of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus, from which to achieve dominance at sea. Mehmed prepared himself well for this crucial venture. ‘There is nothing’, a contemporary Italian wrote, ‘which he studies with greater pleasure and eagerness than the geography of the world, and the art of warfare. He shows great tenacity in all his undertakings, and bravery under all conditions. Such is the man, and so made, with whom we Christians have to deal.’

1

Constantinople by now retained little of its former possessions and wealth. The Byzantine Empire had been reduced to the Despotate of the Morea in the Peloponnese (though this was by now paying tribute to the Sultan), Trebizond on the south-east corner of the Black Sea and Constantinople itself with its immediate surroundings.

This diminished Byzantine Empire was effectively bankrupt. It was unable to collect most of the taxes from distant provinces so could not

maintain the fleet and could barely pay its own troops, let alone mercenaries. Constantinople itself was in decay: a visitor in about 1400 wrote, ‘Everywhere throughout the city there are many great palaces, churches and monasteries, but most of them are now in ruin.’ Another visitor in the 1430s recorded that ‘The city is sparsely populated. The inhabitants are not well clad, but sad and poor, showing the hardship of their lot which is however, not so bad as they deserve, for they are a vicious people, steeped in sin.’

2

This was the common explanation of disaster as divine punishment, which was to colour much of the thinking about Constantinople’s eventual fall. Even the imperial regalia had been sold off and replaced by cheap substitutes: the former gold and silver goblets were now of pewter or clay, gold embroidered cloth had become gilded leather and the jewels simply glass. Only in some of the churches were treasures still to be found.

The man at the head of this sad relic of former glories was the Emperor Constantine XI. He had experience as an administrator and as army commander when Despot of the Morea from 1443 jointly with his younger brother Thomas. He was widely respected for his integrity and tolerance, though some questioned his decisiveness. The Catholic archbishop of Lésvos, a Genoese known as Leonard of Chíos, was in Constantinople throughout the siege, and says of Constantine, ‘whom I always held in the greatest honour and respect’, that he ‘lacked firmness, and those who neglected to obey his orders were neither chastised nor put to death. That good man, so wickedly mocked by his own subjects, preferred to pretend that he did not see the wrongs that were being done.’

3

In 1449, on the death of his father, Constantine left the Peloponnese in the hands of his two brothers Thomas and Dimitrios, and at the age of 44 became the Emperor Constantine XI.

The Turkish threat to his capital soon became clear. At the beginning of winter 1451 Mehmed II, within months of his accession, began preparations for building a castle, Rumeli Hissar, on the European side of the Bosphorus, opposite the fortress of Anadolu Hissar built 40 years earlier on the Asiatic side. Stone and timber were brought in from the east, limekilns to make mortar were set up on the spot, and a huge number of workers was assembled, including 6,000 masons. Work was begun a few months later in March 1452, and completed by August. Now no ship could reach Constantinople from the north without Turkish permission, and in November a Venetian grain ship that tried to do so was sunk by the first cannon shot from the new fortress. Rumeli Hissar was aptly named, by both Turks and Greeks, the Throat-Cutter, blocking supplies to the beleaguered city.

Constantinople too made its preparations. The inhabitants of the surrounding area were brought into the city with their grain supplies. The Emperor sent officials to the Aegean islands to buy food and Chíos provided four shiploads of ‘grain, wine, oil, figs, carobs, barley and all sorts of other crops’.

4

Eight ships arrived from Crete loaded with malmsey, ‘to give the means of life to the city’.

5

Church vessels were melted down into coin to pay troops. The Golden Horn, the narrow inlet running roughly along the north side of the city, was closed off by a boom ‘made of huge round pieces of wood, joined together with large nails of iron and thick iron links’.

6

Another element of Constantine’s preparations was an attempt to settle the divisive question of the union of the Greek Orthodox and Catholic Churches. The schism between Catholic west and Orthodox east had rumbled on for centuries. It was nominally about doctrinal issues, such as whether the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father alone, or from the Father

and

the Son – the famous

filioque

controversy. It was really about whether the Orthodox patriarch in Constantinople was or was not subject to the rule of the Pope in Rome. By now the question of the union of the Churches had become political as well as religious: union was the price Constantinople would have to pay for military help from the Catholic powers.