Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (25 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

Now that Allied forces had opened the Swiss borders from the west, communications with the outside world were much easier. Dulles was able to travel to Paris or London for conferences with his director, Gen. Donovan, and others in the intelligence community. At the same time, Dulles enjoyed far closer liaison with the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps and the G-2 staffs at SHAEF and the U.S. 6th and 12th Army Groups, as well as with the U.S. Seventh Army as they advanced into Germany. In the winter of 1944–45, Dulles reached an agreement with Gen. Masson, head of the Swiss Secret Service, to allow the American legation in Bern to install a secure radio-teleprinter transmitter for direct communications with London, Paris, and Washington. The Swiss authorities were far more amenable to the clandestine activities of the Allies now that defeat was looming for Nazi Germany.

Nevertheless, in February 1945, the military situation both on the German border and in Italy remained problematic. The campaign in the Rhineland had become a protracted battle of attrition as the Allies fought their way up to the Rhine, the

last physical barrier

to Germany’s industrial heartland in the Ruhr. In Italy, the Allies were stalled below the Gothic Line, which stretched from coast to coast across the Apennine Mountains. On both fronts, Allied casualties were depressingly high and German resistance remained dogged. The whole Italian campaign had been a grinding series of costly attacks against successive German hilltop defense lines, and now there was a prospect of the Wehrmacht’s retreating in good order into the mountain reaches of the Alps. In SHAEF there were growing concerns about the existence of a National Redoubt in that region, where the last remnants of the Nazi regime and its diehard defenders could congregate for a final stand that might last for months or even years. The able German commander in chief of Army Group Southwest, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, still had more than a million troops under arms in northern Italy and the Alpine regions. Worse still, the Soviet Union was now claiming hegemony over Austria and Yugoslavia. The latter would give the Soviets possession of warm-water ports on the Adriatic and immediate access to the Mediterranean Sea—a strategic nightmare for the West.

Despite the stern injunctions from London and Washington, Dulles did not ignore the increasing number of approaches he received from various parties and individuals representing members of the Nazi hierarchy—notably Heinrich Himmler—in search of a separate peace agreement with the West. The first came in November 1944 through the German consul in Lugano, Alexander von Neurath. He was followed in December by SS and Police Gen. Wilhelm Harster, the immediate subordinate to SS and Waffen-SS Gen. Karl Wolff, the supreme SS and police leader and de facto military governor of northern Italy. In January 1945, an emissary from Wolff reaffirmed the possibility of a separate agreement for the surrender of all German forces in Italy. To Dulles this seemed too good an offer to refuse out of hand, so he initiated negotiations with Wolff under the designation of

Operation Sunrise

(also subsequently known as Operation Crossword).

The first face-to-face meeting between representatives of Dulles and Wolff took place on March 3, 1945, at Lugano. Paul Blum, the X-2 counterespionage chief for the Bern station, acted for the OSS, and SS Gen. Eugen Dollmann represented Wolff. As a gesture of good will, the Germans agreed to release two prominent Italian partisan leaders—one was Ferruccio Parri, who became prime minister of Italy in June. Five days later, Dulles and Wolff met in person at a safe house in Zurich. With Kesselring’s departure for the Western Front on March 10, the negotiations faltered, but they resumed on March 19 when Wolff actually agreed to permit an OSS radio operator dressed in German uniform to be stationed in his own headquarters at Bolzano for better communications. This agent was a Czech known as “Little Wally,” who had escaped from Dachau concentration camp. Significantly, Wolff also submitted a list of art treasures from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence that he was willing to return intact if the surrender talks prospered.

Throughout these delicate negotiations, Dulles kept Washington informed via Gen. Donovan at OSS headquarters, but from there, news of the contacts was quickly passed to the suspicious Soviets. There were several

Soviet spies in the OSS

, including Maj. Duncan Chaplin Lee, a counterintelligence officer and legal adviser to Donovan, and Halperin, head of research and analysis in the Latin America division. Fearing a separate peace, incensed Stalin cabled Roosevelt and Churchill:

The

Germans have on the Eastern Front 147 divisions

. They could without harm to their cause take from the Eastern Front 15–20 divisions and shift them to the aid of their troops on the Western Front. However, the Germans did not do it and are not doing it. They continue to fight savagely for some unknown junction, Zemlianitsa in Czechoslovakia, which they need as much as a dead man needs poultices—but they surrender without resistance such important towns in Central Germany as Osnabrück, Mannheim, and Kassel. Don’t you agree that such behavior by the Germans is more than strange, [it is] incomprehensible?

Both Roosevelt and Churchill angrily rejected the Soviet leader’s implications, but the damage was done. Roosevelt finally recognized the threat posed by Stalin and the Soviet Union just two days before his death. This episode was, essentially, the beginning of the Cold War.

Stalin now refused to endorse the agreed separation pact of Austria and Germany to allow the former to become once again an independent state. The

U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff expressly forbade

the continuation of the talks with Wolff. Intelligence about these contacts had reached Bormann, and SS and Police Gen. Kaltenbrunner also ordered that such negotiations cease immediately—he and Bormann did not wish to jeopardize their own agenda.

A FELLOW AUSTRIAN, ERNST KALTENBRUNNER

had joined Hitler’s inner circle following the July bomb attempt, when as chief of the Reich Main Security Office he took charge of the investigations leading to the arrest and execution of the plotters and the imprisonment of their families. The fearful retribution exacted by the tall, cadaverous, scar-faced Kaltenbrunner earned him much favor with the Führer. In December 1944, he was granted the parallel rank of General of the Waffen-SS (important in that it gave him military as well as police authority) and the Gold Party Badge. On April 18, 1945, he was appointed commander in chief of the German forces in southern Europe.

Kaltenbrunner’s adjutant, the former SD intelligence officer Maj. Wilhelm Höttl, had already passed information to Allen Dulles concerning the creation of the National Redoubt (see

Chapter 10

). Höttl renewed the connection with the OSS in February 1945 through an Austrian friend of his, Friedrich Westen—a dubious businessman who had profited from expropriations of Jewish property and from slave labor. Both wished to

ingratiate themselves with the Americans

(though not at the expense of offending Kaltenbrunner and, by extension, Martin Bormann), and the stories they told soon became even more misleading and devious.

During early 1944, when Höttl was in Budapest organizing the

transportation of Hungary’s Jewish population

to the extermination camps, he had become friendly with Col. Árpád Toldi, Hungary’s commissioner for Jewish affairs. Now, a year later, Toldi was in charge of the “Gold Train.” This was laden with Hungary’s national treasures, including the crown jewels, precious metals, gems, paintings, and large quantities of currency, much of it stolen from Hungary’s Jews. The train—whose value was put at $350 million (approximately $6 billion today)—was destined for Berlin and was moving westward to escape the advance of the Red Army. As it passed through Austria, Höttl advised Kaltenbrunner of its presence, whereupon the train was stopped near Schnann in the Tyrol and many especially valuable crates were offloaded onto trucks. The contents and the whereabouts of those crates remain unknown to this day. Ostensibly, Höttl was instructed to use the Gold Train as a bargaining chip with the OSS in an attempt to arrange a separate truce for Austria like the deal that was under discussion in Italy.

Yet again, Dulles sent an intermediary—this time a senior OSS officer named Edgeworth M. Leslie—for the first meetings with Höttl on the Swiss-Austrian border. In his debrief to Dulles, Leslie reported that Höttl “is of course dangerous”:

He is a

fanatical anti-Russian

and for this reason we cannot very well collaborate with him … without informing the Russians.… But I see no reason why we should not use him in the furtherance of [common] interests … namely the hastening of the end of the resistance in Austria by the disruption of the [Redoubt].… To avoid any accusation that we are working with a Nazi reactionary … I believe that we should keep our contact with him as indirect as possible.

Believing that Höttl was a conduit to Kaltenbrunner, Dulles agreed: “This type requires utmost caution.” Concurring, Gen. Donovan advised, “I am convinced [that Höttl] is the right hand of Kaltenbrunner and a key contact to develop.”

During these early meetings, Höttl revealed more details about the National Redoubt. He also stated that a Nazi

guerrilla movement known as

Wehrwolf

(Werewolf) had been organized over the past two years, with access to hidden arms dumps, explosives, and ample funds. They could muster some 100,000 committed SS soldiers and fanatical Hitler Youth under the command of another Austrian, SS Lt. Col. Otto Skorzeny—an old friend of Kaltenbrunner’s and Hitler’s favorite leader of Special Forces, whose impressive reputation was well known to the Allies. These “details” were actually disinformation created by Bormann, but they succeeded admirably in causing consternation at SHAEF, particularly to Gen. Eisenhower. As his chief of staff, Gen. Bedell Smith, stated, “We had every reason to believe the Nazis intended to make

their last stand

among the crags.”

SINCE THE BREAKOUT FROM NORMANDY

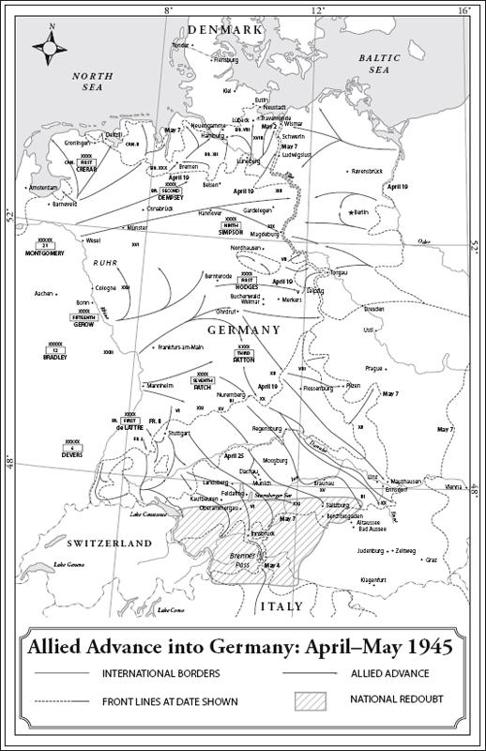

, Gen. Eisenhower had pursued a measured strategy whereby the disparate Allied armies, under their often fractious and competitive commanders, advanced on a broad front. Although ponderous, this plan was politically astute and in tune with the moderate capabilities of conscript armies. Massed firepower, inexhaustible logistics, and overwhelming air support were the answer to superior German tactical performance on the battlefield. Only once did Eisenhower deviate from this strategy, when a failure of Allied logistics halted the broad advance and he accepted the bold plan for Operation Market Garden—the attempted airborne thrust deep into Holland. If it had succeeded, then a rapid advance eastward across the north German plains would have brought Berlin within reach. The capture of the enemy’s capital city and the triumphal parade through its streets following victory has always been the ultimate ambition of all great commanders. But Eisenhower’s ambitions were maturing and he had every reason—both humanitarian and pragmatic—to shrink from the prospect of losing 100,000 GIs during a prolonged and bitter street battle for Berlin.

Over days of brooding, Eisenhower revised his strategy for the campaign in Europe. On the afternoon of March 28, 1945, he declared his intentions in

three cables

. One was a personal message to Joseph Stalin—the only occasion during the war when Eisenhower communicated directly with the Soviet leader. The second was to Gen. Marshall in Washington, and the third was to Field Marshal Montgomery, commander in chief of the British-Canadian 21st Army Group in northern Germany. Against vehement protests from some of his generals—particularly Patton and Montgomery, who each wished to lead an assault on Berlin—Eisenhower stated that the main thrust of his armies was to be southeastward toward Bavaria, Austria, and the supposed National Redoubt. Berlin was to be left to the Red Army. Eisenhower was seeking valuable military plunder, not empty glory.

THE GERMAN ARMY crumbled before the might of the Allies, who rushed to take not just the territory of the former Reich but its art, industrial secrets, and scientists.

BY NOW, THE SWISS AUTHORITIES

were becoming increasingly disconcerted by the number of Nazi emissaries and fugitives trying to cross into Switzerland, many of whom were being held by Swiss border guards. The Swiss indicated to Allen Dulles that it would be desirable if his talks could be conducted more discreetly and preferably not on their territory. They were not trying to be obstructive but they wished to maintain the facade of neutrality to the last. Their greatest fear remained a flood of refugees descending on Switzerland, so an early resolution to the war was their chief priority.