Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (46 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

ON JUNE 6, 1947, ARGENTINA’S FIRST LADY left for a “rainbow” tour of Europe aboard a Douglas DC-4 Skymaster lent by the Spanish government. The metaphor came from a July 14

Time

magazine cover: “Eva Perón: Between two worlds, an Argentine rainbow.” President Perón, most of his government, and thousands of well-wishers saw her off. A second plane followed, carrying the first lady’s wardrobe, the party’s luggage, and numerous boxes (with their contents making a second clandestine trip across the Atlantic)—the “Rainbow” was prudently carrying her pot of gold with her.

Evita was accompanied by

her brother Juan Duarté, her personal hairdresser Julio Alcaraz (who also guarded her extensive collection of jewelry), and two Spanish diplomats sent by Franco to accompany her to her first destination, Madrid. Also on the aircraft was

Alberto Dodero

, a billionaire shipping-line owner who financed the trip. Dodero was a “flashy free-spending tycoon who dazzled even the free-spending Argentines.” His ships would bring thousands of Nazis and other European fascists to Argentina.

Traveling ahead of Eva’s party was Father Hernán Benítez, a Jesuit priest and an old friend of her husband’s. Benítez had been briefed by Cardinal Antonio Caggiano, the archbishop of the Argentine city of Rosario, who was a strong link in the chain that led escaping Nazis to their new lives in Argentina. Caggiano had visited Pope Pius XII in Rome in March 1946 to collect his red hat. At a meeting with Cardinal Eugène Tisserant, Caggiano, in the name of the “Government of the Argentine Republic,” had offered his country as a refuge for

French war criminals

in hiding in Rome, “whose political attitude during the recent war would expose them, should they return to France, to harsh measures and private revenge.” Now it was the turn of the Germans. Bishop Alois Hudal was Bormann’s main contact in the Vatican. A committed anticommunist, the Austrian-born, Jesuit-trained Hudal had been a “clero-fascist” (clerical supporter of Mussolini) and an honorary holder of the Nazis’

Gold Party Badge

. Bishop Hudal was the Commissioner of the Episcopate for German-speaking Catholics in Italy, as well as father confessor to Rome’s German community. In 1944, he had taken control of the Austrian division of the

Papal Commission of Assistance

(PCA), set up to help displaced persons. The PCA, with the help of Bormann’s money, was to form the backbone of the ratlines organized to help escaping Nazi war criminals. (Note:

ratline

, a term often used in reference to Nazi escape routes, is formally defined by the U.S. Department of Defense dictionary of military terms as an organized effort for moving personnel and/or matériel by clandestine means across a denied area or border.)

Among the thousands of men Hudal helped to escape justice were the commandants of both Sobibor and Treblinka extermination camps, SS lieutenants

Franz Stangl

and Gustav Wagner. After escaping American captivity in Austria, Stangl reached Rome, where Hudal found a safe house for him, gave him money, and arranged a Red Cross passport with a Syrian visa. Erich Priebke, Josef Mengele, and Eichmann’s assistant Alois Brunner were just a few of the infamous murderers who also passed safely

through the Nazi bishop’s hands

on the way to Alberto Dodero’s ships.

In 1947, Hudal’s activities were exposed for the first time when a German-language Catholic newspaper,

Passauer Neue Presse

, accused him of running a Nazi escape organization, but this did not stop him. On August 31, 1948, Bishop

Hudal wrote to President Perón

requesting 5,000 Argentine visas—3,000 for German and 2,000 for Austrian “soldiers … whose wartime sacrifice” had saved Western Europe from Soviet domination.

WITH A LARGE ESCORT OF SPANISH FIGHTER PLANES

, Evita’s airliner took off on June 7 from the town of Villa Cisneros (present-day Dakhla) in the Spanish Sahara, destination Madrid. A crowd of three million Madrileños awaited her at the airport, which was decked with flowers, flags, and tapestries. Like visiting royalty, her arrival was marked by a twenty-one-gun salute, and she rode with El Caudillo—“the Leader”—Franco to the El Prado palace in an open-topped limousine, through adoring crowds chanting her name. Awaiting her was a cornucopia of expensive gifts. She was adored in every city she visited; the dazzling first lady behaved like a queen, and Spaniards—after years of civil war and the drab authoritarianism of the Franco regime—took the beautiful Argentinean to their hearts.

The all-conquering

Evita left Spain for Rome

on June 25, 1947. Father

Benítez

would smooth her way in the Vatican with the aid of Bishop Hudal. Two days after she arrived she was given an audience with Pope Pius XII, spending twenty minutes with the Holy Father—“a time usually allotted by Vatican protocol to queens.” However, there was a more sinister side to the Rome trip. Using Bishop Hudal as an intermediary, she

arranged to meet Bormann

in an Italian villa at Rapallo provided for her use by Dodero. The shipowner was also present at the meeting, as was Eva’s brother Juan. There, she and her former paymaster cut the deal that guaranteed that his Führer’s safe haven would continue to remain safe, and allowed Bormann to leave Europe at last for a new life in South America. However, she and her team had one shocking disappointment for Bormann.

PROVING THAT THERE IS

NO HONOR AMONG THIEVES

, the Peróns presented Bormann with a radical renegotiation of their earlier understanding. Evita had brought with her to Europe some $800 million worth of the treasure that he had placed in supposed safekeeping in Argentina, and she would deposit this vast sum in Swiss banks for the Peróns’ own use. As her husband Juan Domingo reportedly said, “Switzerland is the country … where all the bandits come together [and] hide everything they rob from the others.” This treasure—comprising gold, jewels, and bearer bonds—likely went straight to Eva’s trusted contacts in Switzerland, who were awaiting her arrival later in her European tour to set up the secret accounts. The Argentines were leaving Bormann with just one-quarter of his looted nest egg in Argentina. This swindle had been accomplished with the connivance of Bormann’s most trusted Argentine contacts—Ludwig Freude, Ricardo von Leute,

Ricardo Staudt

, and Heinrich Doerge—all of whom had been signatories of the Aktion Feuerland bank accounts set up in Buenos Aires.

The remaining share was still huge, and Bormann

had no option but to accept

this brutal unilateral increase in the premium for his insurance policy. He had been planning his bolt-hole for four years; everything was in place. Hitler was already in Patagonia and with the crimes of the Nazi regime now finally exposed for the world to see, there was nowhere else to go. Within the next nine months both Bormann and SS and Police Gen. Heinrich “Gestapo” Müller planned to settle in Argentina themselves, and they would need their reception arrangements to function smoothly. Bormann knew that Evita was a tough, experienced negotiator, whom he would later describe as

far more intelligent than her husband

.

However, the Bormann “Organization” had a keen memory. After the spring of 1948,

when Müller based himself in Córdoba

and became directly responsible for the security of the Organization, the bankers who had betrayed Bormann would begin to suffer

a string of untimely deaths

. Heinrich Doerge died mysteriously in 1949; in December 1950, Ricardo von Leute was found dead in a Buenos Aires street, and Ricardo Staudt would survive him by only a few months. Ludwig Freude himself, the kingpin of Aktion Feuerland in Argentina, died in 1952 from drinking a poisoned cup of coffee, and Evita’s younger brother

Juan Duarté

met his end in 1954 with a gunshot to the head. Officially he was said to have committed suicide.

AFTER ECSTATIC RECEPTIONS IN LISBON AND PARIS

, Evita took a break at the Hotel de Paris in Monte Carlo, where Dodero introduced her to his friend, the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis. The predatory millionaire would later boast that he slept with her there and

in the morning gave her a substantial check

for one of her many charity organizations.

After her short layover, the “Rainbow” went to join her pot of gold in Switzerland. When she arrived in Geneva on August 4, 1947, she was met by the chief of protocol of the Swiss Foreign Service. He was an old friend;

Jacques-Albert Cuttat

had worked at the Swiss Legation in Buenos Aires from 1938 to 1946. He was deeply involved in the transfer of Nazi assets to Argentina and had been one of the account holders of the many gold deposits in the city’s banks. After meeting Swiss president Philipp Etter and foreign minister Max Petitpierre, Evita dropped out of sight. She joined Dodero and other friends at the mountain resort of St. Moritz, but there was more business to take care of in Zurich, the banking capital of Switzerland’s German-speaking cantons. One meeting took place in a closed session at the Hotel Baur au Lac, where Evita was a guest of the

Instituto Suizo-Argentino

. The president of the institute, Professor William Dunkel, introduced her to an audience of more than two hundred Swiss bankers and businessmen, briefing them on the many opportunities in the “New Argentina.” Many of these opportunities would be under the control of familiar friends and clients.

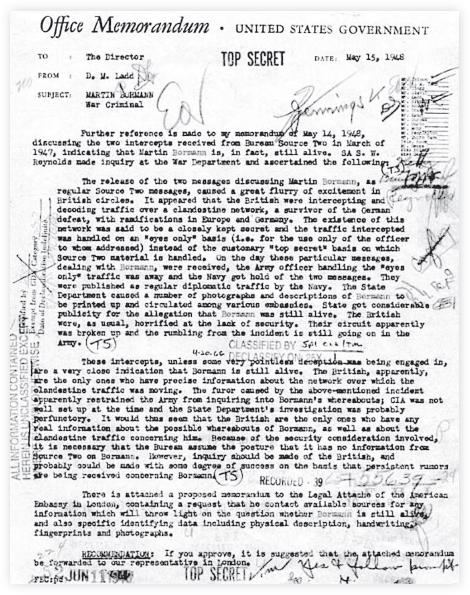

A MAY 15, 1948 memo to FBI director Hoover on a postwar Nazi radio network that had mentioned Bormann by name twice in 1947 before being broken up by the British.

BORMANN RETURNED BRIEFLY TO HIS HIDEOUT

in the Austrian mountains—by now a slimmer, fitter, and poorer man than he had been for years. Although believed by some to be dead, he had been tried in absentia by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg in October 1946 and sentenced to death. In late 1947, the British Army had broken up a clandestine Nazi radio network that had mentioned Bormann twice by name in May 1947,

information the FBI took seriously

(see document on opposite page). On August 16, 1947,

a guide led him and his bodyguards

over a secret route through the Alps to a base just north of

Udine in Italy

. In December he was ready for the next leg of his journey, but it would not pass unnoticed. Capt. Ian Bell, a war crimes investigator based in Italy from the British Army’s Judge Advocate General’s office, had been tipped off about Bormann’s presence. Bell, who had captured a number of wanted Italian war criminals, ordered a spotter plane to fly over the area where he had been told that Bormann and his two-hundred-man bodyguard were gathered. Two days later Bell called in an air strike; an American aircraft flew over and dropped a bomb, a number of the SS men made a break for it and were arrested, and under interrogation they admitted that they were shielding Martin Bormann. The SS told the British that Bormann was planning to flee, and provided details of the route and timing.

Bell and two of his sergeants lay in wait at a spot where they had been told Bormann would pass, reversing their jeep and trailer into a farm driveway. A short while later they saw a small convoy on the road below them—a large black car and two trucks with trailers. Capt. Bell estimated there were sixteen men in total, six in each truck and another three with Bormann in the staff car—too many for him and his two lightly armed NCOs to take on. They followed the convoy until Bell had the chance to use a telephone in a roadside inn to contact his headquarters. He was shocked by what his commanding officer told him: “Follow, but do not apprehend, now I repeat, do not apprehend.” Over the next two days the British officer followed his quarry for more than 670 miles.

The German convoy passed through police and military roadblocks without any trouble, arriving at the docks in the Italian port of Bari in the early hours of a December morning in 1947. From cover, Bell and his men watched the vehicles being hoisted aboard a freighter by cranes and Martin Bormann walking up the gangway. The moment the last vehicle was put into the hold, the cranes swung away, the mooring cables were thrown off, and the ship moved away from the quayside. When Bell checked the ship’s destination with the port authorities later that morning, he was told it was Argentina.