Grow a Sustainable Diet: Planning and Growing to Feed Ourselves and the Earth (9 page)

Read Grow a Sustainable Diet: Planning and Growing to Feed Ourselves and the Earth Online

Authors: Cindy Conner

Tags: #Gardening, #Organic, #Techniques, #Technology & Engineering, #Agriculture, #Sustainable Agriculture

It is nice to have a sweetener in your diet, and even nicer to grow your own. I mentioned maple syrup in the previous chapter. You wouldn’t be growing maple trees in your garden, but you could have them, climate permitting, on your property. You would put one to three taps in a tree to yield 5 to 15 gallons of sap. It takes 10 gallons of sap to boil down to 1 quart (4 cups) of maple syrup.

Although I haven’t been successful getting much syrup from the sorghum I’ve grown, I’ve seen it done. My efforts to squeeze the stalks were with a clothes wringer. The successful efforts I’ve seen are with sorghum presses powered by large animals or gas engines. Occasionally an old sorghum press like that comes up for sale at a farm auction. Bitterroot Tool and Machine, maker of the GrainMaker grain mill, is developing a homestead-sized press that should be ready for sale by the time this book is released.

1

According to the Master Charts, it is possible to get 1 gallon of sorghum syrup from a 100 ft

2

planting. You would need 10 gallons of sap for that. You would also need the right variety for your climate and the right tool to do the squeezing. What little syrup I did get was delicious. September is the time to make sorghum syrup around here and I find myself busy with other projects at that time of year. I’ll stick to growing sorghum for grain. I like to have some around to grind and use in place of wheat when my gluten-sensitive friends visit.

Honey is my choice for a homegrown sweetener. When I started keeping bees in 2007 I could identify with the new gardeners who would show up in my classes at the community college. I had so much to learn and now it was me asking the beginner questions. If you keep bees, or are even thinking of keeping bees, join a bee club and plug into that support system. Bee clubs are a perfect example of the community we need to be part of.

If your bees survive the winter — they don’t always — you could get up to 50 pounds of honey a year from one hive. The first year they are building up the colony, so don’t expect any honey until the second year. Once you know what you’re doing, you can use your own bees to increase the number of hives you have. If you are successful and have more honey than you can use, it can be one of those things you share through gift, trade, or sale. The bees will forage for several miles — yet another example where community is important. Your bees will be at your neighbors and their bees will be paying you a visit. You will be able to find lists of plants with nectar sources. Add as many of these plants as you can to your permaculture homestead. Eventually your perennials will need to be divided — a good opportunity to share with your neighbors. It will benefit you when your bees are out foraging. The busiest time for a beekeeper is spring and early summer.

Pre-planning is great, but in order to know just how you are doing, you should keep records of your crops as you go along. Ecology Action has Data Report and Summary Yield worksheets that the GROW BIOINTENSIVE teachers use for reporting. These are included in their publication

Booklet #30: GROW BIOINTENSIVE

SM

Sustainable Mini-Farming Certification Program for Teachers and Soil Test Stations

2

which is available as a free download at

growbiointensive.org/publications_main.html

. When I am in the garden I write notes on everything I do in 3″ × 5″ notepads, the kind with the spiral on top. Those notes are later transferred to Data Report sheets (I’ve modified the Ecology Action form to suit my needs). I use the information from the data sheets to fill out the Summary Yield form at the end of the year. Make sure to wear clothes with generous pockets when you are working in the garden. That way you have a place to hold a pen and notepad so those items are always with you.

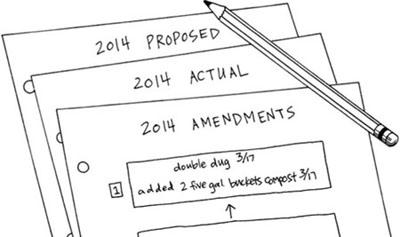

For all of my garden plantings I have a record of what was planted where and when, and what amendments went into those beds. That is done right on my garden map — or rather maps. I record all the crops

on one map, in the beds where they will be planted for the coming year. That is my “proposed” map. I have two more maps that are filled in as the season progresses. On my “actual” map, I fill in the crops in the beds as they are planted, along with the actual planting dates. Another map is my “amendments” record. Each time I add anything to the beds, such as compost, sulfur, or alfalfa meal, I record it there in the appropriate beds. I only maintain the data report record sheets, with the yields, for the crops that I’m studying for Ecology Action teacher certification and specific others I’m interested in. Keeping yield records takes time, no doubt about it. It might be that just knowing how much area you have planted will suffice for you, and if it is enough, too much, or not enough for your family for the year. Having a good garden map filled in with what you have planted in each bed, with the planting times, and maybe the end of harvest, is a lot of information. If you have a tight rotation, with the next crop planted as soon as the bed is free, the planting time of the next crop coincides with the end of harvest of the previous crop. With that information, you could look back in your small notepads, which are your chronological records, and find out more details, such as variety, seed source, etc. The most basic of records is your proposed garden map, as well as your actual and amendments garden maps. I consider those a must.

You could weigh or count each harvest, but that takes the fun out of just eating from the garden. Do that for those crops you are studying and enjoy the rest. It is helpful, however, if you know how much you have put up for the year. Keep a record of how many pints or quarts you may have canned of each thing or how many pounds of potatoes you put away. Making a note on your kitchen calendar might be enough to check back with later. What you have to put on your table will tell you if you’ve grown enough. If not, it is good to have something to look back on to help plan for next year.

Cover Crops and Compost — Planning for Sustainability

G

ROWING A SUSTAINABLE DIET

also feeds the soil. Growing cover crops is one of the best things you can do for your soil. There is no separation between you and the earth that grows your food. Too many people feel distanced from where their food is grown, even though they aren’t actually separated. Everything is connected and everything is important. From my study of nutrition and of the soil, I realized that the same thing is happening in the soil that is happening in our gut. Just as we have to make sure our bodies have the necessary nutrients and a healthy digestive system to assimilate those nutrients, we have to think of the soil in the same way. We need to eat food that is nutritious. It can’t be that way unless the soil has a healthy digestion system and is full of nutrition. Healthy soil produces healthy plants, which feed healthy people, who populate healthy communities, which create a healthy world. Cover crops are food for the soil. They gather what they can from the sun, the rain, the air, and the soil they are grown in, turning it all into food that will feed back the soil with the plants as they decompose, both the above ground parts that you see and the extensive root systems that you don’t see. It is the circle of life. One thing nourishes the next.

When I began gardening, the only information I had about cover crops was accompanied by information about the right time to turn them under with a tiller. Since I didn’t have a tiller, I didn’t consider cover crops, opting instead to cover my garden with leaves each winter. Using leaves is still a good idea, but not everyone has leaves available. As your garden gets bigger, as mine did, you need more and more leaves. Since my son owned a lawn service and one of his services was leaf removal, I had plenty of leaves available to me. There is a limit, however, to how many leaves one person can haul around on their garden, or make that how many leaves one person

wants

to haul around. The fourth year I was growing to sell to restaurants I bought a tiller and expanded my garden area. I only tilled once, and at the most twice, during the season. I maintained grass paths by mowing and treated each bed individually, not tilling the whole garden at one time. The beds in the market garden were 4′ × 75′. I didn’t use the tiller in the smaller gardens, which are the ones you see in my videos. Those were still covered with leaves for the winter. When I learned that I didn’t need a tiller to manage cover crops I made the change to cover crops for all the gardens. Besides, I was beginning to worry that one day I might not have all those leaves available to me. What if Jarod decided to do something else and was not able to bring his leaves here? If my garden program depended on them, what would I do? I could find another source, but I wouldn’t have the same confidence that they would bring me only leaves I could be sure weren’t contaminated with anything harmful.

Beware of Bringing in Outside Inputs

About the time I was thinking about that, I began to hear about a new danger that had been ushered in with the new century. Through the twentieth century organic gardeners gathered carbon materials for mulch and compost from whatever sources they could find. If these materials weren’t grown organically it was thought that the composting action would break things down and life would be good. In 2001 I learned about a new class of chemicals that were being used in the landscape

industry and in agriculture that survived the composting process. These herbicides were used to kill broadleaf weeds in landscapes and to insure weed-free hay and grain in agriculture. If you used the resulting grass clippings, hay, straw, or even the compost made from the manure from animals that had eaten that hay or been bedded with that straw on your garden, your crops could suffer herbicide damage! Furthermore, the damage could persist for several years. I won’t go into specific names of herbicides. As soon as one is banned another will be on the market. You could find more about this by searching “killer compost” on the internet. An early example of this problem that I read about was Penn State University using compost made with leaves from their own grounds. Even the leaves weren’t safe anymore, unless you were sure where they’d been and what was used on the surrounding landscape.

Another consideration for not bringing mulch and compost materials from outside sources into your garden is what is happening to the soil where those materials were grown. Is that soil being depleted to feed your garden? Straw is part of the grain harvest. After the grain harvest, the straw could be returned to the earth. Otherwise, how is that soil being fed? How the soil is fed where your mulch and compost materials came from must be considered part of the ecological footprint of your garden, also.

Considering manure as a garden amendment, in a perfect world it would fertilize the land that grew the food for the animals that produced the manure. Ideally our manure would go back to the ground that feeds us. There are things to consider before you can do that wisely. If you are interested in learning more about recycling human waste, you’ll want to take a look at

The Humanure Handbook

written by Joe Jenkins. Before the new chemicals were a problem, I used to occasionally bring in manure for fertilizer if it was convenient. One time I agreed to take the manure that had been building up at a horse owner’s farm. About the time we had the last of it unloaded at my place, the horse owner mentioned she’d been spraying the manure piles with insecticide to keep the fly population down. That was the last time I hauled in any manure. If you are running chicken tractors (portable chicken pens) over your

garden, their manure is fertilizer, but it is actually the grain you may have bought, that the chickens ate and pooped out, that must be considered when tallying up your sustainability.

You need to have your soil tested. Address any deficiencies with organic amendments as you establish your soil-building plan using cover crops. Whether you have clay or sandy soil, growing cover crops and using them in your garden will build organic matter right there.

I was already studying GROW BIOINTENSIVE methods (which I’ll refer to as Biointensive) by the time I learned of those new herbicides. Compost is a major tenet of this gardening method and it is made from crops grown in the garden just for that purpose. Compost crops are cover crops grown for compost making. The idea of growing enough cover crops to make all my compost was intriguing. With this method the cover crops are cut at maturity, or almost at maturity, and used in the compost piles. Too often gardeners don’t realize the importance of using compost regularly in their gardens. It is not a product that is readily manufactured by those selling you things to start gardening. What you do hear about compost is making your own using your kitchen scraps. Plenty of companies will sell you compost bins to put them in. You would still need a source of carbon, such as leaves. The kitchen scraps are the nitrogen component. Unless you have a really big family and throw away a lot of food, you won’t have enough kitchen scraps to make the compost you need. A compost with a ratio of 30/1 carbon to nitrogen is generally considered a desirable goal. To have a 30/1 compost, your pile would need to be made with an equal amount, by volume, of carbon and nitrogen materials. Biointensive compost has soil added, about 10 percent by volume of the built pile.