Growing Your Own Vegetables: An Encyclopedia of Country Living Guide (5 page)

Read Growing Your Own Vegetables: An Encyclopedia of Country Living Guide Online

Authors: Carla Emery,Lorene Edwards Forkner

Tags: #General, #Gardening, #Vegetables, #Organic, #Regional

HOW TO MANAGE A WORM BIN

Your worm bin can be made of wood, metal, or plastic, although wooden boxes will wear out in just 2 to 3 years unless they are protected with a polyurethane varnish and allowed to dry out once in a while. Building two boxes and rotating their use will greatly extend the lifespan of a wooden bin. The container should be just 8 to 12 inches deep, as this is as deep as the worms will tunnel. A deeper container will only encourage the growth of smelly microorganisms, which live where there is little or no oxygen. Widthwise, your bin should have 1 square foot of surface for each pound of garbage you’ll be adding per week.

Worm bedding not only provides a medium to hold moisture in the bin but also gives you material in which to bury garbage. Good bedding materials include shredded cardboard and paper, manure, and leaves that have been thoroughly dampened but are not so wet as to drip. Add dampened peat moss or cocoa coir to any other bedding to lighten the mix, making it easier for the worms to make their way around the bin. A handful of garden soil added to the bedding helps the worms’ gizzards break down food. Powdered limestone and pulverized egg shells also add grit, reduce acidity, and provide calcium for worm reproduction.

Note: Slake or hydrated lime will kill your worms.

Stock your worm bin with red wigglers (

Eisenia foetida

, also known as the “manure worm” or “red hybrid”), which are capable of consuming large quantities of garbage, reproduce quickly, and thrive in a worm bin environment. Red wigglers have alternating red and buff stripes. Adults are 1½ to 3 inches long and can reproduce every 7 days. Red wigglers may be purchased year ‘round at bait shops and some garden centers in the spring. Check resources online if you do not have a local source, or check with your gardening friends. Anyone with an active worm bin will have worms to share.

Feed kitchen scraps to the worm bin every day or let them accumulate and add once or twice a week. Dig a shallow hole and bury the waste with a covering of about 1 inch of bedding material. With each feeding rotate your digging site to different areas around the surface of the box to evenly distribute and encourage the worms to use the entire bin. Adding more food than your worms can digest will produce a sour smell as the food rots. The rule of thumb is 2 pounds of worms per 1 pound of garbage per feeding. Vegetable and fruit scraps, pasta, bread, tea leaves, and coffee grounds and filters are all acceptable worm food. Do not add meat scraps or fats; these will smell strongly and attract rodents.

With each feeding monitor the bedding’s moisture level and sprinkle with water when necessary. As the worms eat the food and bedding, you will begin to see castings. When the level of castings is such that the bedding is becoming heavy or used up, harvest the vermicompost, a mixture of castings and old bedding material, for use in the garden. Move the old bedding to one side of the bin and fill the empty side with new bedding. Add food scraps to the new bedding; over the course of a few days the worms will move to that side. Remove the now mostly worm-free mature vermicompost. For quicker results, scoop some processed vermicompost into a shallow cardboard-lined tray; over the course of a few hours the worms will burrow down to escape the light. Gently brush the now-worm-free surface compost into a bucket until only a writhing mass of worms remains in the bottom of the tray. Transfer worms into fresh bedding.

Work the harvested worm castings and bedding material into your garden’s root zone or layer it on the surface of the soil for a rich nutritious boost. Brew a liquid fertilizer by steeping castings in water and using the resulting tea to water your plants.

MULCHING

A layer of organic material, newspaper, stone, bark, or even plastic that blankets exposed garden soil will smother weeds as well as provide a physical barrier to evaporation, helping to conserve soil moisture. Mulch is more a technique than an actual garden ingredient but is often used as a noun, as in “I need to buy some mulch to spread in the garden.” Organic mulches are sometimes referred to as

feeding mulches

because as the lower layers decompose they add fertility to the soil as well. Stone and plastic mulches are best at conserving moisture, and black plastic—although not the most attractive option—is often used to warm the soil and get a jump on the planting season.

SOIL NUTRIENTS

The three major nutrients that all plants need are nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). The numbers found on packaged fertilizers, organic and chemical alike, refer to the percentage of these nutrients, always in NPK order, present in the contents of the package. Thus 5-10-5 indicates a formula of 5 parts nitrogen, 10 parts phosphorus and 5 parts potassium.

1.

Nitrogen.

Plants use nitrogen to build healthy leaves and stems. A plant lacking nitrogen gets yellow leaves and grows slowly. Heavy-feeding plants, like corn and brassicas, use nitrogen quickly. Replace nitrogen by adding blood meal, fish meal, cottonseed meal, cover crops, and manure.

2.

Phosphorus.

Plants use phosphorus to grow healthy root systems and flowers. Unlike nitrogen, phosphorus remains in the soil a long time after it has been added. In addition to being richly present in compost, it’s also found in wood ashes, soft and rock phosphates, bone meal, and cottonseed meal.

3.

Potassium.

Plants use potassium to strengthen their tissues, resist disease, and develop the chlorophyll that enables them to make food from sunshine. In addition to compost, it’s found in wood ashes, granite dust, cottonseed meal, kelp, and greensand. Potassium is like nitrogen in that it is quickly lost to the soil and must be replenished.

AN ARGUMENT AGAINST THE USE OF CHEMICAL FERTILIZERS

◗ Plants don’t distinguish between organic or inorganic nutrients, but their impact on soil health is critical.

◗ Chemicals are injurious to soil microbes that naturally produce plant food, creating a sterile environment that must constantly be artificially replenished.

◗ Water-soluble chemical fertilizers leach and contribute to ground-water contamination, and the quick burst of food they do provide does not last for the entire growing season.

◗ Most artificial fertilizers are petroleum based.

◗ Chemical fertilizers do not improve soil texture and water-holding capacity the way mulch, compost, manure, and cover crops do.

GARDEN COMPETITION

WEEDS

A well-nourished plant is a healthy defense against most garden pests. However, there is a limited amount of fertility in any garden. If your garden has one weed for every vegetable plant, then half of your soil’s plant food is going to the weeds and half to your vegetable plants. That means your vegetable plants will be half as big and healthy and productive as they could be if there were no weeds. Although the reality may not be quite that simple, the bottom line is that weeds compete with the plants you are trying to grow for soil nutrients, water, and sun.

Thoroughly till the garden each spring before planting to get rid of weeds that may have over-wintered or sprouted in cool spring weather, and continue to diligently weed during the growing season. Cultivate between rows with a rototiller or a hoe and weed by hand close to the plants. The best time to hand weed is right after a rain, when the ground is damp; roots seem to relax their hold on the soft ground, only to regain their grip when things get hot and dry.

HAND TOOLS

Although a larger garden may employ a rototiller or even a tractor to work the soil, hand tools are invaluable for working in tight quarters and around existing plants.

Spade

—a shallow blunt-nosed shovel used to “plow” or turn over the soil.

Spading fork

—a fork that looks like a pitchfork, but with wide tines, also used to plow the soil.

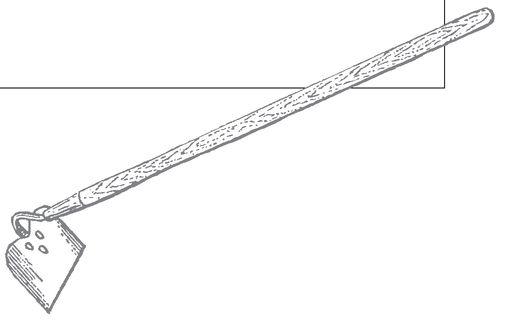

Hoe

—a long- or short-handled tool used for chopping and breaking up dirt clods to create a fine, crumbly soil ready for planting. There are several styles of hoes with narrow or wide, fixed or oscillating blades. All must be sharpened to remain effective as weeding tools.

Rake

—its rigid or flexible tines are used to smooth the seed bed, level the dirt, spread fertilizers, and pull any remaining clods or rocks out of the seedbed.

Trowel

—the pro gardener’s upgrade of a big spoon, used for close-in hand weeding or digging holes for transplants.

GARDEN PESTS LARGE AND SMALL

If you plant a crop and then find that something else ate it before you could, you won’t be the first person it ever happened to. The number of possible plant diseases and plant-devouring insect species, to say nothing of fungi and garden-munching mammals, is legion. The organic gardener’s best defense against bacterial and fungal problems is well-nourished soil and plenty of sunshine and water. Frequent your local nursery and get to know experienced gardeners in your area to learn from their expertise. Most likely they will be able to help diagnose ailing plants and mystery weeds and offer important advice for dealing with regional pests and gardening conditions specific to your area.

Problem mammals

If you grow it, they will come. Critters don’t understand property rights, and many gardens are often and disastrously lost to predators unless the owner takes garden defense seriously. Identify the predator (or the one that got into your neighbor’s garden) and act quickly to prevent the problem or risk losing the fruit (and vegetables) of your labors.

In some parts of the United States, where the natural predators of deer have been eliminated, deer overpopulation has become a serious problem. They have no fear of people or cars, and their competition with each other, combined with the rapid loss of their natural habitat to development, pressures them to boldly graze in suburban yards. Fencing stops them—if it’s high enough. Bury the fencing a foot or so under the ground and it will also serve to keep out rabbits, cats, and poultry. Top the fencing with an electrified wire or two and you may keep out garden-bandit raccoons.

Gophers, moles, and voles all do a great deal of damage with their tunneling. Adding insult to injury, gophers will feed on roots (moles and voles are content to dine on grubs and earthworms). You can try fencing them out with underground barriers, but it can be difficult to get them on the right side—that is, the

outside

of the barrier. Old-timers plant castor beans to repel the diggers, but this is not a good solution in gardens with children or animals as even a single seed of this very toxic plant can kill. Other, far less dangerous but admittedly quirky controls include chewing-gum or instant grits placed at the tunnel opening. An organic, castor oil-based spray may prove the best option of all. To control rats and mice, keep a few hungry cats.

Dogs, scarecrows, a motion-triggered sprinkling device, rotten eggs, hot peppers, garlic, human hair, even urine are all time-tested tools for defending your turf against most garden predators.

Slugs, snails, and insects

These diminutive predators, although much smaller than those just mentioned (and, it could be argued, less sentient and crafty beings) nonetheless can still wreak great havoc on a garden. Slugs are snails with no shells; both are land-dwelling mollusks with a voracious appetite for the stalks and tender leaves of most garden plants. Being soft-bodied and very slimy, slugs and snails are most active in the damp weather of spring; controlling their numbers early in the year will go a long way toward reducing their impact throughout the rest of the season. Use diatomaceous earth, copper stripping, or iron phosphate-based organic baits to combat slugs and snails. A well-placed saucer of cheap beer will also lure them to their demise.