Gudgekin the Thistle Girl (3 page)

The griffin might materialize anywhere at all, sometimes by casually walking through a door or flying through a window, sometimes right out of thin air, since the griffin knew magic. He might materialize, wearing a black bow tie and sporting an expensive ivory-headed cane, at a concert of the Royal Symphony, when the king and queen themselves were in the royal box, and the French horns would all at once for no reason lose their count and come in seven measures early, or the oboe would go unaccountably flat, and everyone would suddenly be on a different page, some of them blasting out with all their might, some of them playing pianissimo. “Haw!” the griffin would remark and would walk out in disgust. The griffin had, in fact, the lowest possible opinion of people, though they somewhat amused him. Since everywhere he went he immediately caused confusionâsince he'd never seen efficiency in anyone but himselfâit seemed to the griffin that stupidity and befuddlement were the essence of human nature, though not of

his

nature. Undependable and changeable as he was, sometimes having three legs and sometimes four, sometimes believing x and sometimes vehemently denying x, he was nevertheless efficient at everything he did, with one exception, as you shall hear.

Observing the consistent stupidity of human nature, the griffin grew arrogant. In his travels to and fro, he was puzzled and confounded by nothing whatever in the world exceptâsuddenly one day, when it dawned on himâthe fact that somehow, when he wasn't there to watch, human beings

did

, occasionally, seem to get things done. Though he scorned human beingsâhardly cared, in fact, whether they lived or diedâthis riddle began to pester him. How was it possible that creatures incapable of doing anything sometimes, nonetheless,

did

things? He would sit in his castle near the top of the mountain overlooking the kingdom, and would turn the question this way and that, upside and downside, the way the mason turned his brick, and after a while the griffin would grow downright cantankerous with frustration, though it did him no good. At last, eyes flashing with annoyance, he would fly back down to have a look at the people again, trying to catch them off guard. It of course never worked. He grew increasingly persistent, popping up everywhere, at all hours of the day and night. Soon all the trains and planes and buses were hopelessly off schedule (many of them were lost, buses coming into their stations in the wrong cities or meandering down dirt roads or into farmers' yards, planes roaring north when they were supposed to roar south and ending up landing on some ice floe, the crew and passengers shivering and stamping their feet). There wasn't a bank in all the kingdom that knew how much money it had or ought to have, if any, and how much had been lost or misplaced in the computer, which seemed to have gone hopelessly insane.

“Who,” said the king, who had called all his people to his palace in the village of Heizenburg, at the foot of Griffin's Mountain, “will rid me of this damnable griffin?”

No sooner had he asked the question than there stood the griffin, gazing out from beside the royal throne like an overgrown dog, surveying the crowd with furiously attentive eyes. Everyone began to think one thing and another, all of it wrong, and one by one they began to wander off, the griffin following, disappointed as usual, until no one was left but the king himself and one old man, a stout, white-bearded philosopher who was said to be wise, who had stayed up late reading the night before, and was now fast asleep on his feet.

“You, sir!” said the king.

The wise old philosopher blinked and gave his head a little shake and woke up. “Your highness?” he said, not quite certain where he was.

“You are willing to volunteer, then, to rid me of this griffin?”

“That,” said the philosopher, “could be a difficult task.”

“Never mind,” said the king, “we'll pay you well. I will give you my daughter's hand in marriage and half the kingdom as her dowry.”

“That won't be necessary,” said the philosopher. “I'm an old man, and though I'm poor, I grant you, I'm used to it and fully content.”

“You mean you'll rid me of this griffin for nothing?”

“Perhaps you could let me have a book or two,” said the wise old philosopher, gazing up thoughtfully at the king's forehead, “or perhaps a supply of pencils, the kind with the pinched-flat erasers, if you know what I mean.”

“I'll give you a truckload of books, my man, and a railroad car filled with pencils with pinched-flat erasers.”

The philosopher sighed. Everyone was always getting carried away. What would he do with a railroad car filled with pencils, and where would anyone find a whole truckload of books worth reading? Well, that was life.

“Come to me again in three days,” said the king, “and listen well: if you haven't gotten rid of the griffin, I'll throw you in jail.”

The philosopher nodded and, profoundly, sighed again. He put his cap on and went out to the street and, thinking back carefully, remembered where his home was and, after making some calculations, drawing invisible numbers or else letters or possibly pictures on his left palm with his right forefinger, chose a path and went there.

His wife was an old battle-ax, or talked like one, though she loved him dearly, for they'd been married many years and understood each other. “And where have you been?” she said.

“I've been with the king,” he said. “He offered me the princess and half the kingdom, but I told him no.”

“Eh, you blockhead!” said his wife, “you might at least have taken his offer of half the kingdom. Look at this hovel we have to live in!”

“What would we have done with half the kingdom?”

“We could have rented it out, fool.”

“That's true,” he said, and sighed more profoundly than ever. “No matter; to get it I'd have had to rid the kingdom of the griffinâwhich, come to think of it, I have to do anyway, more's the pityâand if I haven't gotten rid of him in just three days, the king's going to throw me in his jail.” He rolled his eyes up sadly. “I hope you'll visit.”

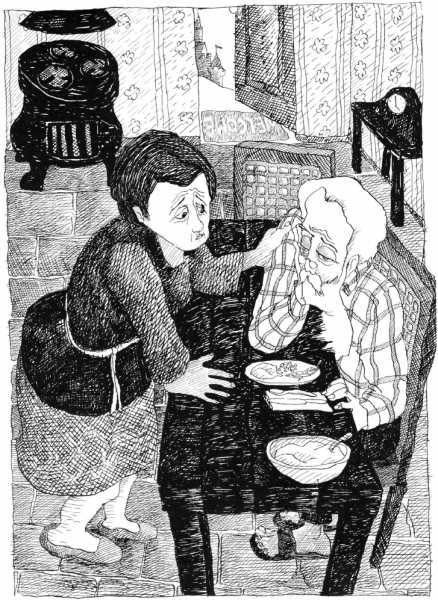

“Don't count on it,” she said. However, she patted his arm and took his elbow, leading him to the kitchen. “Come and eat your supper.”

Wise or not, the stout, white-bearded old philosopher had no idea how to get rid of the griffin. There were no books on the subject, and so far as he could figure, the problem had no rational solution. He went for a walk and his old wife went with him, carrying the lunch basket, and they walked all day except for lunchtime, but the philosopher could think of nothing and at last went back home. “If you're so wise, old dolt,” said the philosopher's wife when they'd finished eating supper, “it seems to me you'd think of some idea.”

“I know,” said the philosopher, “but it's not the way I work. I always start with the assumption that I know nothing, and probably nobody else knows much either, however they may prattle and labor to sound convincing.”

“Nonsense,” said the wife. “You know the world is round. You know oysters don't wear shoes.”

“That's true,” said the philosopher. “You see? I was wrong again.”

“Well, old miserable blockhead that you are,” said the philosopher's wife, not meaning it unkindly, “you're better off than some. A griffin doesn't change your way of thinking.”

“That's an interesting point,” said the philosopher, thoughtfully squinting and pulling at his beard. “It's a point that may well prove useful, if I can manage to remember it.” Then he kissed his old wife fondly and they went up to bed.

Meanwhile the griffin had been up to his usual mischief. He visited the Post Office and the mailmen became so befuddled and confounded that they ended up feeding all the letters to the bears at the zoo. He visited the village's Catholic church, and the priest became so mixed up he converted the congregation to Judaism. He visited the county library and so confused the librarians that when he left,

The Five Little Peppers

was under home economics.

So the first day was over, and the philosopher had two days left.

The second day the old philosopher decided, using a technique that had proved useful sometimes, that perhaps the reason he couldn't answer his question was that he was asking the wrong question. Instead of asking himself, as he'd been doing so far, “How the devil does a person make a griffin go away?” he decided he would ask, “Is a red fire engine red inherently or by definition?” To work on this problem, he went for a walk with his old wife. As before, they carried a lunch basket, or rather she carried it, since she was stronger. They walked all day, except for an hour or so at lunchtime, the old philosopher lost in thought, his old wife muttering to herself and occasionally stooping down to pick a daisy, careful not to bother her old husband. When it was beginning to get dark they went home to have their supper, and after they had eaten it the wife asked, “Well, have you figured it out yet?”

“Tentatively at least,” said the philosopher. “Red fire engines are red by definition.”

“No, blockhead,” she said, “have you figured out how to drive off the griffin?”

“Ah, that,” said the philosopher. “Perhaps I could just go talk to him. Why should a griffin be unreasonable?”

“By definition, lummox,” said his wife.

“Hmm,” said the old philosopher, frowning thoughtfully. “That's very interesting! That's a very interesting point indeed and may prove useful, one way or another, if I can just somehow keep it in mind.”

That day, once again, the griffin had been everywhere, making life in the kingdom so miserable that nothing was accomplished. There were farmers up sitting on the peaks of their barns, no one could say why; there were fishermen boring holes in trees; a local jeweler with an excellent reputation spent the whole day painting six parsnips bright green. The griffin, looking at all this, tipped his head as a chicken might do, or a robin listening for worms as it walks on a lawn. At the end of the day, when the philosopher and his wife were trudging home, the griffin walked with scornful dignity on silent catpaws up the mountain to his castle, pausing only once to look back at the village at the foot of the mountain. The griffin once again tipped his eagle head, baffled, and watched for a moment with his bright black eagle eye for some sign, any sign, of meaningful activity down below. But nothing was happening, or nothing but the day's lingering confusion, and the griffin, in great perplexity, shook his head and continued up the mountain.

So the second day ended, and the philosopher had one day left. This third day he got a sack lunch from his wife and went out of the house alone, for though the idea was depressing to him, he had decided to go reason with the griffin. As he climbed the mountain he analyzed his conundrum from various points of view, and if one thing struck him more forcefully than another, it was this: following out to their logical conclusions his thoughts (insofar as he remembered them) of the previous two days, he would have to say (he thought) that he had in this griffin business a distinct advantage over other men, in that a man utterly confused from the start cannot have his thinking significantly altered by the appearance of a griffin. But though professionally confusedâconfused, that is, by inclination and trainingâhe was no better off than an ordinary man whom a griffin is visiting when it came to understanding a griffin, since a griffin is by definition unreasonable. Nevertheless the old man trudged on, helping himself up the mountain with his cane, and came at last to the castle. It was a splendid castle, but the old man, wandering through it, hardly noticed, for he was lost in thought as usual, and when he found the griffin on his high golden throne he was as befuddled as an ordinary man would be, for a curious problem was molesting his thoughts: what about red fire engines repainted blue? All this he explained to the griffinâor whomeverâfor he hardly paid attention, and the griffinâor whoeverâstared at him as he would at a madman, and at last, with a sigh, the old philosopher went home.