Gudgekin the Thistle Girl (2 page)

“Why, to church, of course!” said the queen of the fairies. “After church we go to the royal picnic, and then we dance on the bank of the river until twilight.”

“Wonderful!” said the thistle girl, and away they flew.

The singing in church was thrilling, and the sermon filled her heart with such kindly feelings toward her friends and neighbors that she felt close to dissolving in tears. The picnic was the sunniest in the history of the kingdom, and the dancing beside the river was delightful beyond words. Throughout it all the prince was beside himself with pleasure, never removing his eyes from Gudgekin, for he thought her the loveliest maiden he'd met in his life. For all his shrewdness, for all his aloofness and princely self-respect, when he danced with Gudgekin in her bejeweled gown of gossamer, it was all he could do to keep himself from asking her to marry him on the spot. He asked instead, “Beautiful stranger, permit me to ask you your name.”

“It's Gudgekin,” she said, smiling shyly and glancing at his eyes.

He didn't believe her.

“Really,” she said, “it's Gudgekin.” Only now did it strike her that the name was rather odd.

“Listen,” said the prince with a laugh, “I'm

serious

. What is it really?”

“I'm serious too,” said Gudgekin bridling. “It's Gudgekin the Thistle Girl. With the help of the fairies I've been known to collect two times eighty-eight sacks of thistles in a single day.”

The prince laughed more merrily than ever at that. “Please,” he said, “don't tease me, dear friend! A beautiful maiden like you must have a name like bells on Easter morning, or like songbirds in the meadow, or children's laughing voices on the playground! Tell me now. Tell me the truth. What's your name?”

“Puddin Tane,” she said angrily, and ran away weeping to the chariot.

“Well,” said the queen of the fairies, “how was it?”

“Horrible,” snapped Gudgekin.

“Ah!” said the queen. “Now we're getting there!”

She was gone before the prince was aware that she was leaving, and even if he'd tried to follow her, the gossamer chariot was too fast, for it skimmed along like wind. Nevertheless, he was resolved to find and marry Gudgekinâhe'd realized by now that Gudgekin must indeed be her name. He could easily understand the thistle girl's anger. He'd have felt the same himself, for he was a prince and knew better than anyone what pride was, and the shame of being made to seem a fool. He advertised far and wide for information on Gudgekin the Thistle Girl, and soon the news of the prince's search reached Gudgekin's cruel stepmother in her cottage. She was at once so furious she could hardly see, for she always wished evil for others and happiness for herself.

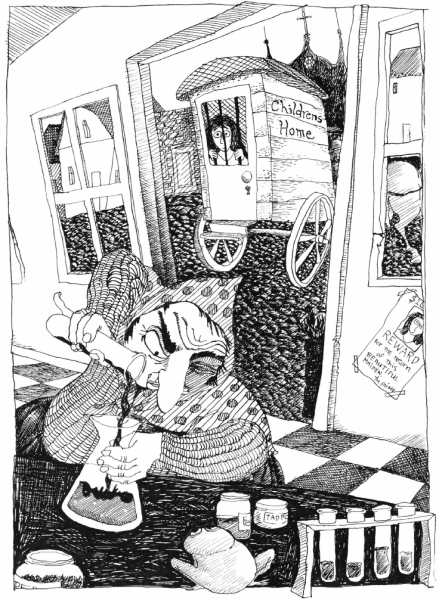

“I'll never in this world let him find her,” thought the wicked stepmother, and she called in Gudgekin and put a spell on her, for the stepmother was a witch. She made Gudgekin believe that her name was Rosemarie and sent the poor baffled child off to the Children's Home. Then the cruel stepmother changed herself, by salves and charms, into a beautiful young maiden who looked exactly like Gudgekin, and she set off for the palace to meet the prince.

“Gudgekin!” cried the prince and leaped forward and embraced her. “I've been looking for you everywhere to implore you to forgive me and be my bride!”

“Dearest prince,” said the stepmother disguised as Gudgekin, “I'll do so gladly!”

“Then you've forgiven me already, my love?” said the prince. He was surprised, in fact, for it had seemed to him that Gudgekin was a touch more sensitive than that and had more personal pride. He'd thought, in fact, he'd have a devil of a time, considering how he'd hurt her and made a joke of her name. “Then you really forgive me?” asked the prince.

The stepmother looked slightly confused for an instant but quickly smiled as Gudgekin might have smiled and said, “Prince, I forgive you everything!” And so, though the prince felt queer about it, the day of the wedding was set.

A week before the wedding, the prince asked thoughtfully, “Is it true that you can gather, with the help of the fairies, two times eighty-eight thistle sacks all in one day?”

“Haven't I told you so?” asked the stepmother disguised as Gudgekin and gave a little laugh. She had a feeling she was in for it.

“You did say that, yes,” the prince said, pulling with two fingers at his beard. “I'd surely like to see it!”

“Well,” said the stepmother, and curtsied, “I'll come to you tomorrow and you shall see what you shall see.”

The next morning she dragged out two times eighty-eight thistle sacks, thinking she could gather in the thistles by black magic. But the magic of the fairies was stronger than any witch's, and since they lived in the thistles, they resisted all her fiercest efforts. When it was late afternoon the stepmother realized she had only one hope: she must get the real Gudgekin from the Children's Home and make her help.

Alas for the wicked stepmother, Gudgekin was no longer an innocent simpleton! As soon as she was changed back from simple Rosemarie, she remembered everything and wouldn't touch a thistle with an iron glove. Neither would she help her stepmother now, on account of all the woman's cruelty before, nor would she do anything under heaven that might be pleasing to the prince, for she considered him cold-hearted and inconsiderate. The stepmother went back to the palace empty-handed, weeping and moaning and making a hundred excuses, but the scales had now fallen from the prince's eyesâhis reputation for shrewdness was in fact well foundedâand after talking with his friends and advisers, he threw her in the dungeon. In less than a week her life in the dungeon was so miserable it made her repent and become a good woman, and the prince released her. “Hold your head high,” he said, brushing a tear from his eye, for she made him think of Gudgekin. “People may speak of you as someone who's been in prison, but you're a better person now than before.” She blessed him and thanked him and went her way.

Then once more he advertised far and wide through the kingdom, begging the real Gudgekin to forgive him and come to the palace.

“Never!” thought Gudgekin bitterly, for the fairy queen had taught her the importance of self-respect, and the prince's offense still rankled.

The prince mused and waited, and he began to feel a little hurt himself. He was a prince, after all, handsome and famous for his subtlety and shrewdness, and she was a mere thistle girl. Yet for all his beloved Gudgekin cared, he might as well have been born in some filthy cattle shed! At last he understood how things were, and the truth amazed him.

Now word went far and wide through the kingdom that the handsome prince had fallen ill for sorrow and was lying in his bed, near death's door. When the queen of the fairies heard the dreadful news, she was dismayed and wept tears of remorse, for it was all, she imagined, her fault. She threw herself down on the ground and began wailing, and all the fairies everywhere began at once to wail with her, rolling on the ground, for it seemed that she would die. And one of them, it happened, was living among the flowerpots in the bedroom of cruel little Gudgekin.

When Gudgekin heard the tiny forlorn voice wailing, she hunted through the flowers and found the fairy and said, “What in heaven's name is the matter, little friend?”

“Ah, dear Gudgekin,” wailed the fairy, “our queen is dying, and if she dies we will all die of sympathy, and that will be that.”

“Oh, you mustn't!” cried Gudgekin, and tears filled her eyes. “Take me to the queen at once, little friend, for she did a favor for me and I see I must return it if I possibly can!”

When they came to the queen of the fairies, the queen said, “Nothing will save me except possibly this, my dear: ride with me one last time in the gossamer chariot for a visit to the prince.”

“Never!” said Gudgekin, but seeing the heartbroken looks of the fairies, she instantly relented.

The chariot was brought out from its secret place, and the gossamer horse was hitched to it to give it more dignity, and along they went skimming like wind until they had arrived at the dim and gloomy sickroom. The prince lay on his bed so pale of cheek and so horribly disheveled that Gudgekin didn't know him. If he seemed to her a stranger it was hardly surprising; he'd lost all signs of his princeliness and lay there with his nightcap on sideways and he even had his shoes on.

“What's this?” whispered Gudgekin. “What's happened to the music and dancing and the smiling courtiers? And where is the prince?”

“Woe is me,” said the ghastly white figure on the bed. “I was once that proud, shrewd prince you know, and this is what's become of me. For I hurt the feelings of the beautiful Gudgekin, whom I've given my heart and who refuses to forgive me for my insult, such is her pride and uncommon self-respect.”

“My poor beloved prince!” cried Gudgekin when she heard this, and burst into a shower of tears. “You have given your heart to a fool, I see now, for I am your Gudgekin, simple-minded as a bird! First I had pity for everyone but myself, and then I had pity for no one but myself, and now I pity all of us in this miserable world, but I see by the whiteness of your cheeks that I've learned too late!” And she fell upon his bosom and wept.

“You give me your love and forgiveness forever and will never take them back?” asked the poor prince feebly, and coughed.

“I do,” sobbed Gudgekin, pressing his frail, limp hand in both of hers.

“Cross your heart?” he said.

“Oh, I do, I

do!

”

The prince jumped out of bed with all his wrinkled clothes on and wiped the thick layer of white powder off his face and seized his dearest Gudgekin by the waist and danced around the room with her. The queen of the fairies laughed like silver bells and immediately felt improved. “Why you fox!” she told the prince. All the happy fairies began dancing with the prince and Gudgekin, who waltzed with her mouth open. When she closed it at last it was to pout, profoundly offended.

“Tr-tr-

tricked!

” she spluttered.

“Silly goose,” said the prince, and kissed away the pout. “It's true, I've tricked you, I'm not miserable at all. But you've promised to love me and never take it back. My advice to you is, make the best of it!” He snatched a glass of wine from the dresser as he merrily waltzed her past, and cried out gaily, “As for myself, though, I make no bones about it: I intend to watch out for witches and live happily ever after. You must too, my Gudgekin! Cross your heart!”

“Oh, very well,” she said finally, and let a little smile out. “It's no worse than the thistles.”

And so they did.

The Griffin and the

Wise Old Philosopher

I

n a certain kingdom there lived a griffin. He was, like all griffins, a puzzle and an annoyance, and he had, like most griffins, the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion, or at least that was usually the case. Griffins are, above all, undependable. He was not, in all fairness, the worst kind of monster that a kingdom might be plagued by: he did not eat childrenâor anyone else, for that matterâin the way some griffins are purported to do; he was not slovenly or crass in his personal habits. All he did, in fact, was spread consternation and confusion wherever he appeared.

An electrician, for example, might be repairing an electric clock, a thing he'd done a thousand times and more, and suddenly there would be the griffin standing there, watching him with interestânot talking distractingly in his creaky, half-parrot, half-oldwomanish voice, and not soundlessly pacing on his large lion feetâdoing nothing, in fact, absolutely nothing, and yet suddenly the old electrician would squint and purse his lips and, after a moment, take his glasses off, and he would look at the small, colored wires in his two hands, and for all his training and experience, would have no more idea which wire went where than would a camel. “

You

, griffin!” he would say, or he might even be so confused he couldn't think of the word

griffin

. “Haw

haw!

” the griffin would say, richly amused and profoundly disgusted by the stupidity of mankind, and would stride away. His going away would be no help, for that day at least, to the electrician. The day was ruined.

Or an experienced mason might be putting up a wall for a Sunday school, his assistant standing over by the mortar-mixing trough, sloshing the cement and sand and water back and forth, keeping them well mixed, and the griffin would appear, maybe ten feet away, lying in the grass like a cat, wings folded along his back, beaked head lifted, his beady black eyes watching with sober curiosity, and suddenly, for all his experience and training, the mason would find himself studying a question that had never gotten into his head before: “Which side of a brick is up and which side

down?

” A lunatic question you may say, and so it is, for the top and bottom of a brick are as identical as the mirror-image of a chicken and the chicken looking in at it. Nevertheless, the mason in his sudden bafflement could do nothing more about that wall until the question was settled in his mind, and the longer and harder he looked at that brick, the more certain he would grow that the brick's top and bottom were impossible to tell apart, so there was no way on earth he could be certain that the top was the top, and the bottom the bottom, and in his fury and frustration he would burst out crying. Meanwhile his assistant would have wandered off, forgetting he was part of the job, imagining he'd merely stopped to observe for a moment, as people all do when there's construction underway.