Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (18 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

The battle against SOPA was won. But the war against corporate agendas to undermine Internet freedom including online access to medicine continues. Public health authorities, such as the FDA, should operate under our most basic medical principle—the Hippocratic Oath—do no harm. Thus, even in protection, or drafting, of the law, any action to prevent people from obtaining needed medications online or offline, including supporting legislation such as SOPA, violates fundamental medical ethics and threatens our human rights.

PATRICK RUFFINI

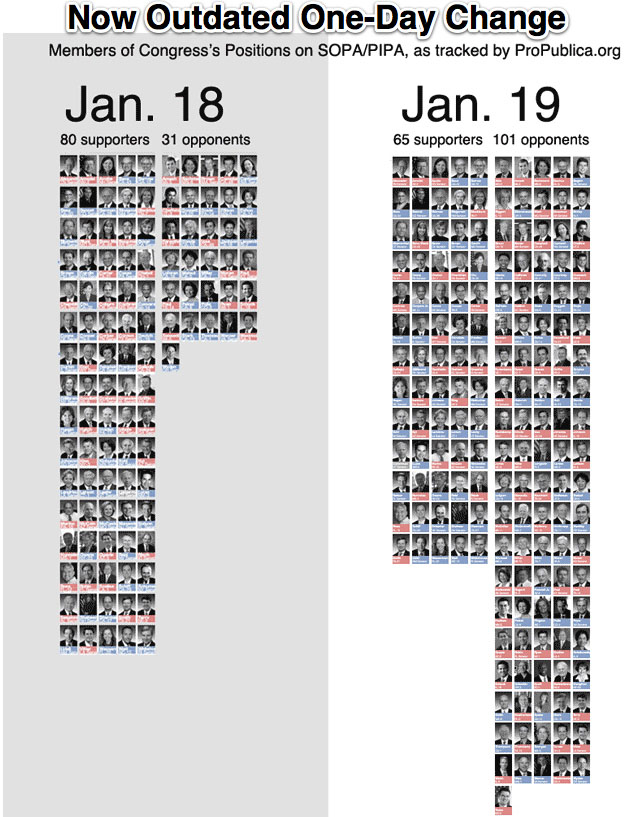

Once the dust had settled from the January 18th blackout, no single image was shared and emailed more than this one, created by ProPublica:

This chart shows support for SOPA/PIPA in Congress on January 18, 2012 and then later on January 19, 2012. In just one day, dozens of lawmakers finally saw the writing on the wall and quickly aligned themselves with the Internet community.

The fight against SOPA and PIPA is often told as a story of the Internet grassroots. But it is also a story about Congress, and how the good guys can sometimes

maneuver within the legislative process to win. The opposition went from having no legislative strategy to engineering a total collapse of the position held by the chairman and ranking members of Judiciary in both houses, winning over top leadership on both sides.

It is instructive to note the position from which we started. Two different versions of online censorship passed the Senate Judiciary Committee by unanimous 18–0 votes. Oregon Democrat Ron Wyden stood as the Senate’s lone opponent, and was twice able to place a “hold” on the bill, delaying further action. (As revealed in the Judiciary Committee’s vote count, Wyden was not even a member of the relevant committee tackling the issue.) In 2010, Wyden’s hold was accurately described as killing the COICA bill—which had emerged too late that year to pass. When Wyden did the same after the initial Judiciary Committee vote on PIPA in May 2011, the “hold” merely ensured delay. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid would still be able to bring the legislation to the floor with a simple motion to proceed, which was the precipitating factor in the January 18, 2012 Internet blackout.

Arrayed against Wyden were forty senators who would eventually cosponsor PIPA. Thirty-one of these senators remained as cosponsors of S. 968, the PROTECT IP Act, through the end of the 112th Congress.

This forty-to-one tally allowed the proponents of the bills to portray the opposing position as unworthy of consideration. Unable to marshal technical arguments for how the proposed scheme for combating online piracy would actually work, lobbyists for the content industry would resort to sob stories about jobs lost to piracy, and derision of opponents. Almost nobody—not the press, not the lobbyists, and not the policy people involved on either side—believed we could win in any conventional sense.

In retrospect, and as is often the case when David eventually beats Goliath, the hubris of the proponents made them sloppy, causing them to expect a staid, lobbying-only playbook that would be thrown out the window once millions of people got involved.

When they were first hired by NetCoalition to build a lobbying strategy against PIPA in the lead up to the spring 2011 vote in the Senate Judiciary Committee, Andrew Shore and Jim Jochum didn’t see victory as an option. “It wasn’t even about winning,” recalled Shore. “It was about coming in to just run out the clock.”

In the summer of 2011, the Senate was completely lost. In theory, the filibuster makes it easier to stop legislation in the Senate than in the House, but mostly only when party politics is involved. Bipartisan populist coalitions, like those against SOPA and PIPA, tend to get less purchase in the Senate than in the House.

Shore saw the House as the key to everything, and this premise was also behind the anti-SOPA/PIPA strategy of Don’t Censor the Net. Approached from the outside, if the issue could be framed as an issue of government overreach, rank-and-file Republicans, many of them Tea Party freshmen, could be rallied to oppose the bills as a sort of default anti-government, anti-Obama

Administration position. Shortly after the new Congress convened, we made a point of going to the annual Conservative Political Action Conference with flyers talking up the dangers of giving Barack Obama and Eric Holder’s Justice Department broad discretionary power to take down websites.

On the inside, the story was more nuanced, since lobbyists typically don’t march into Hill offices using “big government” as a boogeyman. There, it was about poisoning the atmosphere, creating a sense of uncertainty and chaos around the bill. Winning was about understanding what the leadership would need in order to not move forward on the issue.

“What dynamic do you create so the leaders say, ‘You know what, it’s not worth it, we’re not going to touch it?’” recalled Shore, “Then we kind of worked backwards from there.”

At the outset, the vocal House opposition was as meek as that in the Senate. Only Silicon Valley Democrat Zoe Lofgren could be counted on as a firm ally in early 2011, raising questions that February about the Department of Homeland Security’s takedown program for domestic websites, and the fact that eighty-four thousand run-of-the-mill websites were shut off for three days as part of a misdirected order against a domain hosting company. The incident also made for an instructive horror story about the lack of due process involved: the government had only meant to target one site, but in the process, had plastered a notice on tens of thousands of sites effectively accusing their owners of child pornography.

In late summer, however, the opposition began to gather steam. The quiet steps taken in this period highlight the impact that substance-driven outreach to Congressional offices can have in convincing members not only to switch sides on a bill, but to become leaders in the opposition.

Today, Senator Jerry Moran and Representative Darrell Issa are considered two of Congress’s biggest Internet enthusiasts. Issa—chairman of the Government Oversight Committee, which handles investigations of alleged wrongdoings in the Executive Branch—is depicted as a stick-figure policeman on his Twitter profile, and was the first to slap a “Censored” banner on top of it to protest SOPA.

Prior to entering Congress, Issa was a successful entrepreneur and inventor of the Viper car alarm. As an IP rights-holder, Issa could have been considered a natural supporter of expanded intellectual property enforcement, and remained undecided on the issue until the fall. But he was also a strong supporter of tort reform, and PIPA had introduced a private right of action enabling Hollywood and rights-holders to sue directly in order to compel Internet companies to take down websites.

Issa weighed both sides, and with his legislative director Laurent Crenshaw, vetted SOPA and alternative proposals from the technology industry. The handful of lobbyists working the issue for the technology industry had hoped Issa, with his IP background, could serve as a bridge to Lamar Smith to soften the bill. But once Issa was in, he was all-in. Presented with proposals to merely improve the worst-of-the-worst in SOPA, Issa’s office scoffed: they would kill it.

Issa was in a unique position in that he was also a member of the Judiciary Committee—one of the first members of one of the committees of jurisdiction

to speak out against SOPA. As a chairman himself, he set up a chairman-on-chairman battle that threatened to fracture the House Republican conference, which could force the GOP leadership’s hand on the bill.

On June 23, 2011, Kansas freshman Jerry Moran had signed on as a PIPA cosponsor, one of a wave of Senate backbenchers that Hollywood lobbyists had recruited in their drive to the symbolically crucial goal of fifty cosponsors. Four days later, he withdrew his cosponsorship with no explanation. Moran’s departure from the bill was a mystery to our coalition. Who had gotten to him, we wondered? Regardless, it provided an immediate boost: the ranks of senators who had rejected PIPA had doubled, from one to two.

At the time, this was momentum.

In the months following, Moran, like Issa, would become a vocal advocate for Internet startups, sponsoring the Startup Act 2.0, a series of legislative proposals designed to foster Internet entrepreneurship. Ironically, it took a senator from largely rural Kansas to appreciate the value the Internet could bring in reviving the Heartland’s struggling economy. Even in the months after SOPA, Moran evinced little in the way of tech-savvy (in contrast to Issa’s ebullient jump into social media, holding forth in a reddit AMA) but he put the issue this way: In Kansas, a startup could create one hundred jobs—and really make an impact on the local economy.

In the summer of 2011, we weren’t necessarily looking to Issa and Moran to lead a movement. As Shore explained it, we simply needed allies to get a “better” bill. What the House would do was shrouded in mystery, as the expected introduction of the bill kept getting pushed back, stretching into the fall. The hope from the anti-PIPA forces was that they could play to conservative resistance to private rights of action to craft a narrow bill that would serve as a Republican counterpoint to PIPA. The approach was centered around a simple strategy for dealing with rogue sites called “follow the money.”

Follow the money focused squarely on cutting off payment processing to rogue websites, and would form the crux of Issa and Wyden’s alternative bill introduced in December, titled the OPEN Act. Unlike the skin-deep remedy of DNS blocking (where the content would remain online, just not at a domain name), follow the money had already shown its effectiveness in cutting off online offshore gambling. Credit card companies, including Visa and MasterCard, already had well-established policies against supporting merchants who dealt in pirated or counterfeit goods, making censorship concerns a non-issue. Studies released during the debate showed that 95% of the trade in spam or online counterfeit goods flowed through just three offshore banks. This approach addressed these choke-points. Ironically, though the DNS blocking provisions in SOPA and PIPA represented a drastic departure for how the Internet was architected and policed, its net impact on rogue website activity would have been minimal.

DAVID SEGAL

We had a pretty clear sense of what our role in the effort needed to be, at least for the time-being: Demand Progress was substantially under-resourced, and certainly wouldn’t win this fight on its own, or as party to the small coalition that was responsible for organizing the bulk of the anti-COICA and PIPA work to date. We’d have to fend off the bill’s backers long enough to build a more robust coalition, or for somebody to intervene from the heavens.

It seemed obvious that the libertarian-right should be opposed to this legislation: after all, it was a robust new regulatory regime being foisted upon Americans by one of conservatives’ very favorite boogeymen: Hollywood.

We got incredibly lucky during the spring, when Mark Meckler—then the co-coordinator of the Tea Party Patriots—agreed to co-host a conference I was organizing with Lawrence Lessig. I hounded him over the next couple of months, begging him to take a deep look at PIPA and start to muster conservatives in opposition to it. Patrick pestered him as well.

I’ve had a bit of a fetish for alliances between the Left and Right for a while now. Not the pissant yearning for middling agreement somewhere in that supposedly vast chasm that separates the tendencies of the corporatist wings of the two major parties—striving for a Grand Bargain around fiscal policy, for instance. The notion that there’s insufficient bipartisanship in Washington is transparently absurd. Please see the following counterexamples: foreign policy writ large, subservience to the banks, bipartisan deficit-hawking, an ongoing multi-presidency assault on civil liberties, and, of course, support for SOPA and PIPA. No, what gets me going is those moments where there’s actually true-to-God agreement among left- and right-ideologues

Opposition to the bank bailouts, auditing the Federal Reserve, ending the P.A.T.R.I.O.T. Act, even votes against wars and defense spending will all draw a not-insignificant amount of cross-partisan support, from people on both sides of the aisle who straight-up agree about things. Our political systems haven’t completely accommodated to those alliances, so they still offer the occasional chance to throw a wrench into machinations of the powers-that-be, relative to those issues where such solidarity can be achieved.

There are of course substantial, critical differences between the left and the right which should not be downplayed, but opportunities for this sort of cross-partisan organizing are often overlooked because of undue presumptions of utter, complete polarization between the two major parties and the rank-and-file Americans who affiliate with one or the other of them. The standard single-axis left-right ideological paradigm is fraying—if it ever truly held to begin with—and the dynamic quickly degenerates into even greater confusion when one strives to map ideological tendencies onto the mainstream political parties.