Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (61 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

I want to spend a few minutes tonight sharing my view of how that happened, and what it means to our economy and our society going forward.

At Union Square Ventures, we invest in networks. We were the first institutional investor in Twitter, Tumblr, Foursquare, Etsy, and Kickstarter. We have also invested in many other less familiar networks in markets like education, employment, and finance. As we spend time with these networks, we learn more and more about their extraordinary economics.

They are easy to bootstrap, create remarkable efficiencies, optimize the value of scarce resources, and cost very little to promote.

Like most of these networks, Foursquare was built on open source software and its services are delivered over the Internet. They were able to grow to over one hundred thousand users on less than $25,000. Craigslist radically reduced the cost of classified advertising. They replaced the call centers, printing presses, trucks and trees that used to be necessary to alert the world that you wanted to sell your couch—with a digital photo and a drop-dead simple electronic posting mechanism. Airbnb has re-invented the way travelers are matched with beds, and in the process enabled hundreds of thousands of people around the world to capture the value in their spare bedroom.

Twitter, Tumblr, and Foursquare spend little or nothing to acquire new users or to propagate a new feature. We hear a lot about viral marketing but I did not internalize its implications until I watched David Karp, the founder of Tumblr, introduce a new feature: by hiding it.

When I was an entrepreneur in the software business we spent a ton of money and time to introduce a new feature. We did analyst tours, issued press releases, threw parties, and bought billboards to promote a new feature. David hides it. But then he sends an email to a few popular bloggers and tells them if they mouse over this one section of the site, they will see a drop down menu with a couple of new capabilities. He encourages them to play with the features but asks them not to tell too many people about it because he is not committed to releasing it generally.

So they use the features and of course someone reading their blog sees they have done something cool and asks how they did it. Two weeks later there is a kid in Akron, Ohio, telling a kid down the street, “I am not really supposed to tell you this but if you mouse over this part of the site.” And the feature is now ubiquitous.

These economics create enormous opportunity. The combination of low costs, cheap capital and relatively free access to markets has created an unprecedented era of decentralized, emergent, start-up innovation. By creating novel new services and dramatically reducing the cost of existing services, that innovation has unlocked value for consumers that they are now redeploying in other new services.

But at the same time, that process, the classic creative destruction of free market capitalism, has created new challenges for incumbent industrial companies.

For the last 130 years the economy has been dominated by firms structured as bureaucratic hierarchies. That model worked well to mass produce products for mass consumption, but the inefficiency of communicating customer needs up through the hierarchy and management decisions back down, and the natural tendency of any organization to protect its current organization structure makes it difficult if not impossible for bureaucratic hierarchies to innovate as quickly as the emerging network-based model of decentralized innovation.

So the incumbents who have a fiduciary duty to their share holders to maximize profits look for ways to stave off competition from networks and protect their current cost structures. Increasingly, they ask policymakers and regulators to change the rules in ways that tilt the market in their favor.

Policymakers and regulators who have longstanding relationships with these incumbents are receptive to these requests because they are usually couched in language about the safety or security of consumers, and because there are only a few people—most of whom are in this room—who are explaining the risks of these proposed policies and regulations.

Over the next few years there will be a steady stream of these requests. The hotel lobby in New York City has already convinced the city council to outlaw temporary hotels. The bill was presented as a consumer safety measure to prevent slumlords from turning dilapidated tenements into squalid, unsafe hotels. The councilmembers never considered the bills’ impact on Airbnb but the hotel lobby knew exactly what their proposed language meant.

The Research Works Act played out in a very similar way in Washington. Its original sponsors understood it as the elimination of a government mandate

that forced researchers to embrace a specific business model. The academic publishers who sponsored the bill knew very well that it would slow competition from open-access journals.

I could go on and on.

Telecom companies asking regulators to impose new burdens on Skype, or toy manufacturers asking regulators to force Etsy sellers who make hand-carved wooden toys to be subjected to a rigorous certification process that only makes sense for large manufacturers.

The point is that we have to step back and see these policy proposals as the inevitable byproduct of the transformation of our economy. We have to see them as a part of the competition between the bureaucratic hierarchical model for the creation of economic value that has dominated the economy for the last 130 years and the new emergent economics of networks.

We need to be smart enough to recognize that it is not consumers asking for these regulatory or legal restrictions, it is the incumbents. We need to defend the freedom to innovate because it is critical to the health of our economy. Our economy is today one of the most innovation-friendly economies in the world. Until recently, no one investing in or creating a business on the Internet would have considered building their business anywhere else.

But the recent enforcement actions against MegaUpload and JotForm have forced entrepreneurs and investors in Internet services that enable users to upload content to the web to rethink where their businesses are based.

I don’t know the particulars of the JotForm case and it is very hard to defend the behavior of the MegaUpload founders but it is also impossible to ignore the fact that the site takedowns made it impossible for hundreds of thousands or millions of users to get to the completely legitimate content they stored on those services.

In the weeks that followed those takedowns every one of our portfolio companies had to reconsider where their users’ data is stored. A lot of them are now wondering if they should be moving to domain name servers outside this country.

The Internet is a global network. There are countries out there that recognize the opportunity to create an Internet Enterprise Zone. They are working to establish a policy framework that protects user data, and more broadly the freedom to innovate. I cannot tell when or even if data and the good systems administration jobs that go with it will move offshore, but I can tell you that the conversation has already started.

But networks are not just critical to our economy. They are crucial to a vital civil society. It is pretty clear that we will not be able to continue to live in the manner in which we have become accustomed. We are very likely not going to be able to support things we value like the arts or social services in the way that we’d like. We are going to have to learn to do more with less.

Networks can play a role here as well. Kickstarter, a crowd-funding network, launched only a few years ago, will provide more support for creators this year than the National Endowment for the Arts.

In the UK, lawmakers are just as frustrated as we are that banks are still not lending to small businesses, but the irregulatory framework has allowed FundingCircle, a peer-to-peer network of lenders and borrowers, to flourish. Lawmakers have begun encouraging their constituents not just to “shop local” and “eat local.” They are asking them to “lend local,” creating a brand new source of working capital for small businesses and an emotional and financial return for lenders.

There are many other examples of networks making a difference in civil society from mapping slums in Kenya, to getting at-risk kids in New York to take better care of their health, to empowering mothers in Boston to take on gang violence. If we defend the freedom to innovate, we will find lots of ways to efficiently deliver important social benefits.

Of course, we should expect the same resistance from the incumbent bureaucracies in the public sector who regard those services as their turf.

Innovation depends on keeping the costs of innovation down, making sure that financing is available, and making sure that markets are accessible. It does not depend on R&D grants or targeted industrial policy.

So the next time you see a piece of legislation that has an impact on an open Internet, software or business method patents, copyright enforcement, free and fair competition, open government, or cyber security, I urge you to see it through the lens of the competition between incumbent industrial hierarchies and emergent networks.

Consider who is sponsoring the legislation. Does it really protect consumers or does it protect the business models and cost structures of the incumbents?

I recently heard a woman from the Occupy movement say the most poignant thing. She said “no one is coming for us.” Her generation does not expect the government to be there when they need it, nor do they think the incumbent industrial hierarchies are structured or motivated to address the challenges they expect to face.

Remarkably, she was not depressed, defeated, or bitter. She was determined. The kids who grew up inside AOL chat rooms and came of age on Facebook have an intuitive understanding of the power of networks that our generation will never have.

They are not asking us to fix the problems we left them with. They are asking us not to get in their way as they try to dig themselves out. I think we owe them that.

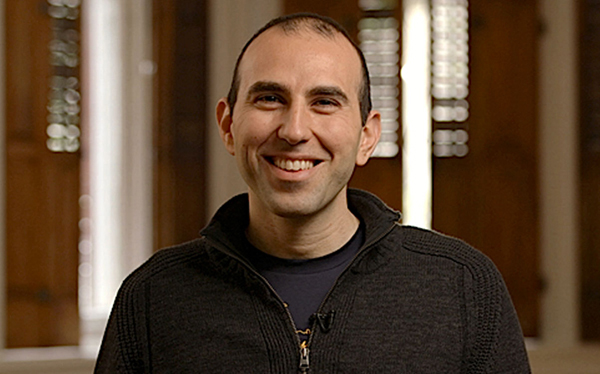

MARVIN AMMORI

Marvin Ammori is internationally recognized as a leader in Internet law and public policy, combining first-rate legal analysis with creative political strategies. In 2012, Fast Company named Ammori one of the 100 Most Creative People in Business in 2012 (#32) for his role in helping to defeat the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and Protect IP Act (PIPA) bills. He served as the head lawyer of Free Press, as a technology advisor to the 2008 Obama Campaign and Transition, and now represents some of the nation’s largest companies

.

The debate over SOPA and PIPA should be a turning point in the way people think about the First Amendment, which forbids government officials from abridging the freedom of speech and press.

Traditionally, for perhaps 100 years, people tended to think of the First Amendment as something judges enforce. It is a part of the Constitution and a limit on what Congress, the executive branch agencies, and states and cities could do. In this First Amendment mythology, an official in a “political” branch of government (the mayor, the governor, the President) tries to silence someone (the dissenter, the flag burner, the hate speaker). Then the heroic judge strikes down the law, sets free the prisoner, or refuses to impose a fine.

It was seen, in short, as a judicial right. As a judicial right, the public had little involvement. Judges are not elected. They do not count votes. They accept amicus briefs, but they also simply adjudicate issues. Unlike Congress, they are somewhat insulated from politics.

Increasingly, however, the most important decisions determining our freedom to speak to one another here (and around the world) are those that will shape the emerging architecture of the Internet. Judges do not make these decisions. For many decades, scholars told a joke that that freedom of the press belonged to those who owned one. The Internet changed all of that. The Internet is our most important speech medium today—because it enables anyone to reach a wide audience without relying on a newspaper editor or broadcast producer. The Internet has an open architecture for speech and innovation—that promotes greater levels of commerce and communication.

The Internet has been an effective popular speech medium not primarily because of judicial decisions. We have not relied on speech heroes wearing black robes but on engineering decisions in technical standard-setting bodies, on decisions made by lawyers at technology companies over whether to take down videos or keep them up, on decisions made at federal agencies, and those made at Congress, including the notice-and-takedown provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, which protects websites like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter from copyright infringement suits based on their users’ posts—so long as these companies follow simple takedown procedures.

If judges are not the key players, does that mean the First Amendment is irrelevant? No. Judges are bound to uphold the Constitution—but so is Congress. So are members of federal agencies. So are state government officials. So is the President. They all took an oath to uphold the Constitution, and so they should all be guided by the principles in the First Amendment. They have sworn not to restrict freedom of speech. The decisions that govern our basic communications infrastructure—from broadcast TV rules to cable, phone, and Internet rules—are all subject to that requirement.