Hamilton, Donald - Novel 01

Read Hamilton, Donald - Novel 01 Online

Authors: Date,Darkness (v1.1)

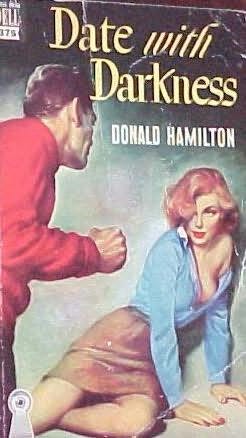

Date with

Darkness

By DONALD

HAMILTON

Rinehart

&: Company, Inc.

New York

TORONTO

Copyright,

1947, by Donald Hamilton

Printed

in the

United States of America

American

Book-Stratford Press, Inc.,

New York

All rights reserved

HE

TOOK DOWN her suitcase and her fur coat. She said she did not have a hat. She

let him put the coat over her narrow shoulders, like a cape, and sat down

beside the suitcases on the seat to wait out the uncomfortable last minutes

while be braced himself, in the aisle, against the people crowding past.

Daylight was snatched from the windows as, slowing, they entered the station.

He followed her along the platform with

the two suitcases and they climbed the stairs into the rotunda where, stepping

out of the flood of people into an eddy behind a pillar, she stretched out her

hand for her bag. "Can't I

... ?

" he asked.

"No, I'm taking a taxi. This is

fine," she said. "Thanks an awful lot." Even in the low-heeled

pumps she reached to a level with his eyes. He could just see over her and no

more.

"Well," he said, "thanks

for the company.

"I'll call you if I can," she

said.

"The Cooper.

I'm sorry to be so

indefinite."

"That's all right," he said.

"Well," she said, "so

long."

He watched her, tucking the purse under

her arm, carry the small black suitcase away from him. Her name, she had said,

was Janet Haskell. He did not for a moment believe she would call him. He felt

very lonely and thrust his unlighted pipe into his mouth for company.

It made him feel a little better to walk

into the hotel bar with the two gold stripes on his sleeve in a city where

nobody knew him. It made him feel a little reckless and carefree, and he was

pleased to be six feet tall even if

underweight,

and

to have the uniform fit him seventy-seven dollars and fifty cents worth, and to

have fifteen days leave, even if he did not know what he intended to do with

it. He ordered Scotch and, tasting it, leaned his elbow on the bar and looked

about the dark, crowded, low-ceilinged room. His mind started absently to work

on a plausible letter to his mother explaining why he had not spent this leave,

probably his last in uniform, at home like the others.

"Pardon me, sir," said a voice

behind him.

He turned to see a large young man in an ill-fitting

ensign's uniform. His glance touched the left breast of the blouse and was

relieved to find no ribbons. It put them on the same footing, and he had the

extra stripe.

"Weren't you on the train, sir?"

the large young man asked.

"Well, I was on a train," he

said.

I thought I recognized you, sir," the

ensign said.

f

wondered if you could tell me where we

could get a room. My wife's with me and we don't know

New York

at all."

"Frankly, neither do I," said

Phillip Branch. "You've tried the desk?"

"Oh, yes," said the ensign.

"And we've called every hotel in town.

Constance

is calling some friends,

but..."

"Well, I'm sorry," Branch said

uncomfortably. I really don't know...."

"There's

Constance

now," said the younger

man, and a small girl wearing a heavy green skirt and a limp white cotton shirt

came between the tables to

them :

"Nothing," she said tiredly,

pushing back her hair.

they've

moved." She spoke

to the ensign, ignoring Branch in her weariness. "Have you got a drink for

me" she asked.

Branch felt a slow, trapped resentment as

he looked from one to the other of them. He watched the girl taste her drink

and thought, I wonder at what rummage sale she picked up that skirt? The

bulkiness of the skirt, the ill-fitting looseness of the shirt, and the

low-healed flatness of her laced brown oxfords gave her a dumpy look that

annoyed him because she was quite a nice looking girl. She caught him watching

her and smiled at him uncertainly. The ensign apologized quickly, and they

introduced themselves. They were Paul and Con stance

Laflin

,

from

New Orleans

.'

"Anyway," said the girl

bitterly, "that's the last place we're from."

"Oh, cheer up, darling," said

Paul

Laflin

. "It's not that bad."

"Well, first it was indoctrination,

at

Parkhurst

, and then," she said, ticking them

off on her fingers, "there was that course you took in

Philadelphia

, and then

New Orleans

, and now here. Not bad for

nineteen months." Branch glanced at the ensign, a little surprised.

"Nineteen months"

"Just about," said the younger

man.

"How about you, sir?"

"A little over three years,"

Branch said.

"All in

Chicago

, except

indoctrination."

"Some people have all the luck."

The girl smiled quickly to erase the sharpness of her tone.

The man asked hastily, "Where did you

go, sir"

"

Tucson

,

Arizona

," Branch said. He

grinned. "And did we sweat. How was it at

Parkhurst

"

As they talked he tried to remember what

someone had told him about

Parkhurst

, but he could not

remember it. You heard a little about all of them, and they were, after three

years, all the same. There was always the signal drill where someone was very

clever, and the fouled-up navigation lesson, and the day when half the section

passed out in ranks from the typhoid shots. After three years, indoctrination

school was a faintly pleasant memory of a time when you felt you were really a

naval officer, or would be when you got through, and not merely a civilian in

disguise. You never felt that way again.

'Well, look," said the girl

presently, interrupting them, "look, I'm starving.

"Do they serve chow in here?"

asked the ensign. ""Would you care to join us for lunch, sir?"

Sure," said Branch. He had resigned himself to eventually giving up his

room to them, but he wished the ensign would not call him "sir" so

assiduously.

Paul

Laflin

turned from asking a question of the bartender. "He says go up the ladder

to the second deck. They don't serve down here."

Branch rubbed his face to smooth away a

grin as he followed them. When we've gone up the ladder, he thought, to the

second deck, I suppose we turn to starboard.

My God.

Salty as hell,

ain't

he? The younger man stood aside

to let him, by virtue of his superior rank, go first through the door after the

girl who dropped back to walk beside him as they mounted the stairs.

"Paul was sure you were

married," she said shyly. "We had a long argument about it."

He glanced at her. "You mean on the

train?"

"Yes, you were sitting with a girl,

weren't you?"

"Oh", he said, a little

embarrassed. "Yes. That's right, I was, but....."

She was all right, too," the younger

man said, walking on the other side of him.

"Was she a friend

Of

yours?" Constance

Laflin

asked.

He shook his head. "She just happened to

sit beside me." Paul

Laflin

grinned. "How

did you make out sir?"

"I don't know yet," Branch said,

laughing. "I didn't get her phone number. But she said she might call

me."

"There isn't much to do on a train

except talk about the people," Constance

Laflin

said a little apologetically." We just happened to notice you because of

the uniform. We were behind you in the car.

"You

don't realize how much army there is

Until

you start

to travel," her husband said. It maker you feel kind of lonely.

They turned into a small dining room that

had the functional and impersonal brightness of a well-kept washroom. The

change from the intimate dusk of the bar was almost embarrassing Phillip Branch

seated the girl and sat down beside her, the ensign sitting down opposite him,

and seeing them both clearly for the first time he had a momentary feeling of

being completely out of touch with them, as if there had been a pane of glass

between them and him. It was probably, he reflected, his knowledge that they

were deliberately working him for his room that gave him this sensation, and he

opened his mouth to tell them they could have the damned room but the girl

started to speak and they both stopped at once and laughed. "Go

ahead," he said.

"Oh, I was only going to ask you

where you're from, Mr. Branch."

"

Indianapolis

," he said.

"You don't talk quite like a

Midwesterner."

"Well, I lived in

Boston

till I was fifteen,"

Branch said.

"Are you on your way to visit your

relatives there the younger man asked.

Branch laughed. "Not if I can help

it:" After a moment he said, "I just thought I'd spend one leave away

from home while I still had a uniform to impress the girls with."

"You're staying in

New York

, then?" the girl

asked.

"Until I get tired of it," Brand;

said. "I've got fifteen days. If I get bored maybe I'll give the uncles

and aunts a break, later on··· He looked at the ensign's sleeve. There were

three kinds of braid: the silver-base that paled as the gold rubbed off; the

copper-base that turned red; and the nylon that, not being gold at all,

remained a bright garish yellow. The cheaper uniforms generally came with the

copper or nylon braid; and Paul

Laflin's

single

stripe was a dull rust color.

"Looks like you're about due for

another half stripe," Branch said, indicating the worn braid. He thought,

nineteen months; they're running longer all the time. He had made his half

stripe in fourteen.

"Well, it depends how my new C.O.

feels about it," Paul

Laflin

said.

Branch looked up at him sharply, a little

startled.

The younger man said, "Well, I was

sort of stuck down in

New Orleans

. That's one reason I asked

for a transfer. I didn't want to stay an ensign all my life."

"We were thinking of having a

baby," his wife said quickly. "And the way rents were down

there..."

Branch looked from one

to the other of them, and he could feel his heart beating heavily, and he saw

that he was about to make an officious ass of himself.

"You mean they wouldn't promote

you?" he asked the ensign.

Paul

Laflin

shrugged. "The whole place was full of

j.g.'s

already...."

"Look," said Branch slowly,

"look, would you mind

.. ."

He grinned

uncomfortably to make his request seem less arbitrary. "...

would

you mind showing me your

"I don't ..." The younger man frowned

across the table. "What's the matter, sir?"

"For Christ's sake," said

Phillip Branch. "For Christ's sake belay that Sir." will you?"

"What's the matter, Paul?" the

girl asked quickly, leaning forward.

Paul

Laflin

grinned and shrugged. "I don't know. He wants to see my identity

card."

She stared at Branch and, suddenly

throwing back her head, laughed delightedly. Then she stopped laughing.

"Oh, for heaven's sake!"