Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love (12 page)

Read Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love Online

Authors: Myron Uhlberg

O

ne morning toward the end of summer, my father shook me awake with his strong printer’s hands. An annual tradition was about to be set in motion.

“School starts thirty days from now,” his hands fairly screamed at me. “There is a big sale on boys’ suits at Mr. R. and H. Macy’s store today. We must hurry!”

My father, who had never owned a single suit as a boy, now insisted that his son have a new one every year. Every summer, about a month before the beginning of the school year, as regular as clockwork, the ritual of buying a new suit for me would begin. And once begun, the ritual was my signal that summer was over. Oh, sure, the calendar on my wall still said “August,” but this day signaled that the calendar was lying; I could almost feel the chill of autumn on my bare skin.

“Time is short. Hurry! Hurry!” he signed with an insistent choppy movement of his hands. “We’ve got to get a move on before all the good stuff is snapped up.”

“Good stuff? Snapped up?” I mumbled under my breath. I didn’t have to mumble. My father wouldn’t hear me. He was deaf. But I did have to be careful, because he could read my lips.

Slowly I dragged myself out of bed. I was in no rush to begin this day. A day that would bring me no joy. A day that was sure to be wall-to-wall embarrassment as I played the go-between, negotiating the transaction of buying a suit with my father on one side, and a bunch of unsympathetic, impatient, hearing salesmen all working on commission on the other side. For them, time was money. My father had all the time in the world to select just the right suit for his son. They had none to spare.

“We’ll start with Mr. Bloomingdale,” my father’s hands informed me. “His basement has a ton of suits. All with two pants. And he has the best prices in the city.”

Best prices?

I thought. Sure, but in all the time we shopped there, we never bought a single suit. Bloomingdale’s basement was just that, the starting point in an endless day.

“Who knows?” my father added. “If we’re lucky, we’ll find a two-for-one sale.”

At the end of two subway rides that took us from the far reaches of the oceanside fringe of Brooklyn to the treeless streets of Manhattan, we exited the station into a world far different from the one we had left behind. Lexington Avenue and 59th Street on the island of Manhattan was to West Ninth Street at the outer edge of Brooklyn “as different as St. Petersburg was to Odessa,” my grandmother Celia always said. That is, when she said anything at all.

Holding my hand, my father marched me across Lexington Avenue, already clogged with trucks and cabs manned by sweating and swearing drivers, their bleating horns and curses falling unheard on my father’s deaf ears. Safely arriving on the other side of the avenue, my father dropped my hand, and now, freed from my grasp, his hands flung excitement in every direction. “What a great day this is! Me with my son Myron, out to buy a suit. A

beautiful

day. Listen! Can you hear the sunshine sound on the ladies’ red dress in the window? And look at the light of the sunshine! See how it breaks up into diamonds in the puddle at the curb! Smell the exhaust from the automobiles! Can you taste it on the back of your tongue?”

For my father, who could not hear, every other sense was heightened to compensate for his loss. He even claimed to “hear” the sound of color.

Leaving the sunlit street, we descended into the artificial light of Bloomingdale’s basement. That’s where the two-for-one suits were located. And there were thousands of them hanging in that vast, poorly lit room. I could swear my father licked his lips in anticipation at the sight of all that wool.

Being ever practical by nature, he always began by instructing me to try on the suits that were sewn of the heaviest wool fabrics. Pattern didn’t matter: plaids, stripes, herringbone. Weave was not an issue: serge, gabardine, worsted. Price was of no concern. Nothing mattered except sheer weight.

“These are great,” his hands assured me, while his mobile face accompanied his happy hands with a big self-satisfied smile.

“These are bulletproof suits.”

“Great,” my doubting hands said. “These suits would serve me well in the invasion of Europe. What German soldier would shoot at a kid from Brooklyn wearing a plaid suit like this? And if he did, how surprised he’d be when the bullets bounced off the lapels.”

I could tell by my father’s expression that my jokes fell flat. They did not deter him at all. His only response was “Follow me.”

Off to the dressing room we went, my father with ten wool suits clutched to his chest, me following dutifully behind. The way his arms drooped, I figured the suits must have weighed about a hundred pounds.

“Where is a salesman?” my father signed in the suddenly deserted room. “They’re never around when you need one.”

I didn’t have the heart to tell my father that at the sight of us, every salesman in the place had scurried off, as the cockroaches did late at night when I turned on the light in our kitchen to get a glass of water. Our fruitless, sales-less annual visits had not been forgotten by those who worked on commission: no sale, no commission. Every summer in came my father, and off ran the salesmen.

“Never mind,” my father signed. “I know Mr. Bloomingdale’s inventory like I know the contents of my closet. It never changes.”

Suit after suit I tried on. Modeling each one for my father while being rotated by him, like a chicken on a spit, I stood in front of a huge tilted floor mirror.

“Not right,” he said. “Bunches up in the back. Makes you look like a little hunchback man. The same as in that sad movie. You know, the man who rings the church bell. Try this one next.

“Too tight. Try the next one.

“Plaid makes you look fat. Now you look like a little fat man-boy. Like Lou Costello.” He laughed, but as my father looked not in the least like Bud Abbott, I did not join in his hilarity. Actually, by then I usually felt like crying.

“Try this one.

“The stripes make you look like a string bean boy. Green suit makes you look good enough to eat. Like a vegetable. Maybe we’ll take you home and Mother Sarah will cook son Myron in his new green string bean suit.”

Oh, what a day this would be! His jokes were as unfunny to me as mine had been to him.

“Try this one on next.”

Suit after itchy wool suit I tried on and modeled for my father.

None were satisfactory to his eye.

Hours passed. Suit after suit was plucked off the rack and brought to me in the dressing room. Suit after suit took its place on the dressing room wall, then the dressing room bench, and finally, stacked up neatly, on the dressing room floor.

When my father had exhausted every single suit in my size, as well as sizes I could never grow into before they went out of style—if they had ever been in style—he threw up his hands, announcing, “Well, that’s it for Mr. Bloomingdale. He had his chance. We gave him first crack.”

“But we never,

ever

buy a suit from Bloomingdale’s,” I pointed out to him. “We come here every year. I try on every suit they have in my size, even sizes too large for me. ‘You’ll grow into this someday,’ you say. And after all those solids and plaids and stripes and herringbones, you always say, ‘Well, that’s it for Mr. Bloomingdale.’”

“Quality,” he signed patiently, as if explaining to a backward child. “That’s what we’re after. Only the very best suit is good enough for my son Myron.”

Holding my hand in his left hand while signing abbreviated signs with his right, my father launched us into the stream of traffic on Lexington Avenue.

“Next stop, Mr. R. and H. Macy. Largest store in the world.” I looked at the expansiveness of my father’s sign as he let go of me for a moment, his hands spread wide describing the size of R. H. Macy, and my heart dropped at the mere thought of the visit.

Safely on the other side of the avenue, after my father had stared down a fast-approaching taxi, daring it to hit us, we boarded a bus, then ducked into the subway for a short ride downtown.

Climbing out of the station at 34th Street, we stood at the entrance to the home of Mr. R. and H. Macy. An enormous place, it occupied an entire square block, street to street, avenue to avenue. I couldn’t begin to imagine how many suits in my size it might contain. I wondered if Mr. R. and H. Macy was open twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. There was no way we could get through all the suits in this place before school started.

With a look of fierce determination on his face, my father took my hand. We whirled into the store through the giant revolving door. Along with a score of other shoppers, we were swept into a waiting elevator, which rose with a sudden acceleration, before quickly dumping us into the middle of the suit department.

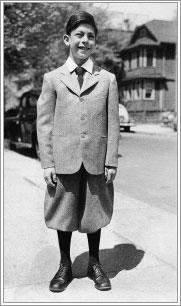

In my new R. & H. Macy suit

Spread out before us was a vast ocean of suits, row upon endless row, quite possibly all the suits that had ever been made, except for those poor two-pants-per-jacket versions hanging in Mr. Bloomingdale’s emporium, which had utterly failed my father’s quality test.

The thought of the sheer quantity of sheep that had been clipped to produce the wool that had been woven into the cloth that was used to make these endless flocks of suits staggered my imagination. In my mind’s eye, I could see all those poor, cold, naked, shivering sheep huddled together on a grassy hill somewhere in Scotland, trying to stay warm.

I glanced up at my father and saw a look of pure happiness spread across his face, which soon gave way to a mask of determined yet optimistic resolve.

Taking a firm grip on my hand, he waded bravely into the oncoming waves of hanging suits, stretching out to the horizon of banked elevators, with me following haplessly in his wake.

Now the second act of this dreadful play began—and this would also be a long one, as Mr. R. and H. Macy had if possible even more suits than Mr. Bloomingdale, and even fewer salesmen in evidence, for the clothing salesmen in Macy’s also saw my father coming and if anything ran faster than those at Bloomingdale’s. Undaunted, as resolute as Richard Burton seeking the source of the Nile, my father trudged forward, leading me by the hand as if I were John Hanning Speke:

By God, we’ll find the source of the Nile or die trying.

O

nce we had returned to our neighborhood at the end of one of these epic days, the annual purchase held securely in the hands of my triumphant father, the third act of our annual drama would begin. As we exited the Sea Beach line subway stop at Kings Highway, my father would sign, “You’ve been a good boy today. I’m proud of you. You were a big help to me. And you were fun company. Now for your reward.”

Our neighborhood candy store was our Arabian Nights Bazaar, containing not just candy but other delights, some of them ordinary and practical, some exotic. Here we bought our brand-new spaldeens (when we had split the old one in two, with a perfectly executed swing of a sawed-off broomstick) and chocolate Kisses in their silver wrappers. Button candy, dripped as dots onto tissue-thin paper, was sold by the inch, each multicolored sugary button to be sucked singly into our greedy mouths and savored (when we weren’t trying to extract the bits of paper stuck on the backs of the buttons from between our teeth). The most exciting purchase of all was the wax lips. Ruby red, perfectly molded, and shaped into a perpetual pouty smile in wax, they were as flavorful as a Yahrzeit candle. But with these bulbous red lips clenched firmly between our front teeth, we kids would parade gleefully around the neighborhood, pressing our faces into the thighs of every grown-up we encountered. The

why

of it all escapes me to this day.

“Choose anything you want,” my father signed. “Even two things today.”

Wow,

I thought.

Where do I begin?

My father was the model of patience. “Take your time,” he said. And so in unconscious imitation of him in the department stores, I looked at every comic book in the candy store, handled every small toy, and fingered every small trinket except for that near-universal favorite, the tin clicking frog. Every kid in Brooklyn knew that by repeatedly clicking a clicking frog, they could drive their parents nuts in five minutes flat. But that didn’t work with mine, of course. Finally I settled on a Batman comic and a set of wax lips. “I’ll wear them when we get home,” I told my father. “Mother won’t recognize me.” My father smiled at the image of me walking through our front door, smiling like an idiot at my mother with my ruby-red lips.