Hanns Heinz Ewers Alraune (31 page)

Read Hanns Heinz Ewers Alraune Online

Authors: Joe Bandel

Tags: #alraune, #decadence, #german, #gothic, #hanns heinz ewers, #horror, #literature, #translations

That’s when I learned the opposing lawyers

have united, they already had a long conference the day before

yesterday. A couple of newspaper reporters were there as well. One

of them was sharp Dr. Landmann from the General Advertiser. You

know very well, your Excellency, that you haven’t put a penny of

money into that paper!

The roles are well divided. I tell you–this

time you won’t get out of the trap so easily!”

The Privy Councilor turned to Herrn

Gontram.

“What do you think, Herr Legal

Councilor?”

“Wait,” he declared. “There will be a way out

of it.”

But Manasse screamed, “I tell you there is no

way out of it! The noose is knotted, it will tighten–you will hang,

your Excellency, if you don’t give the gallows ladder a quick shove

ahead of time!”

“What do you advise then,” asked the

professor.

“Exactly the same thing that I advised poor

Dr. Mohnen, whom you have on your conscience, your Excellency! That

was a meanness of you–yet what good does it do if I tell you the

truth now?

I advise that you liquidate everything you

possibly can. By the way, we can do that without you. Pack your

bags and clear out–tonight! That’s what I advise.”

“They will issue a warrant,” opined the Legal

Councilor.

“Certainly,” cried Manasse. “But they will

not give it any special urgency. I already spoke with Colleague

Meir about it. He shares my opinion. It is not in the interest of

the opposition to create a scandal – the authorities would be happy

enough if they could avoid one as well.

They only want to render you harmless, your

Excellency, put an end to your doings–and for that–believe you

me–they now have the means. But if you disappear, live somewhere in

a foreign land, we could wrap this thing up quietly. It would cost

a lot of money–but what does that matter? They would be lenient on

you, even today yet. It is really in their own interests to not

throw this magnificent fodder to the radical and socialistic

press.”

He remained quiet, waiting for an answer. His

Excellency ten Brinken paced slowly back and forth across the room

with heavy, dragging steps.

“How long do you believe I must stay away?”

he asked finally.

The little attorney turned around to face

him, “How long!” he barked. “What a question! For just as long as

you live! You can be happy that you still have this possibility at

least. It will certainly be more pleasant to spend your millions in

a beautiful villa on the Riviera than to finish out your life in

prison! It will come to that, I guarantee you!–By the way, the

authorities themselves have opened this little door for you. They

could just as easily have issued the warrant this morning. Then it

would have already been carried out! Damned decent of them, but

they will be disgusted and take it very badly if you don’t make use

of this little door.

If they must act, they will act decisively.

Then your Excellency, this night will be your last night’s sleep as

a free man.”

The Legal Councilor said, “Travel! After

hearing all that it really does seem to be the best thing.”

“Oh yes,” snapped Manasse. “The best–the best

all the way around, and the only thing as well. Travel!

Disappear–step out–never to be seen again–and take the Fräulein,

your daughter, along with you–Lendenich will thank you for it and

our city as well.”

The Privy Councilor pricked up his ears at

that. For the first time that evening a little life came into his

features, penetrating through the staring apathetic mask,

flickering with a light nervous restlessness.

“Alraune,” he whispered. “Alraune–if she goes

with–he wiped his mighty brow with his coarse hand, twice, three

times. He sank down, asked for a glass of wine, and emptied it.

“I believe you are right, Gentlemen,” he

said. “I thank you. Now let’s get everything in order.

He took the stack of documents and handed

over the top one, “The Karpen brickyards–If you please–”

The attorney began calmly, objectively, gave

his report. He took the next document in turn, weighed all the

options, every slightest chance for a defense, and the Privy

Councilor listened to him, threw a word in here and there,

sometimes found a new possibility, like in the old times.

With each case the professor became clearer,

his reasoning better thought out. Each new danger appeared to

awaken and strengthen his old resiliency. He separated out a number

of cases as comparatively harmless. But there still remained more

than enough to get his neck broken.

He dictated a couple of letters, gave a lot

of instructions, made notes to himself, outlined proposals and

complaints–then he studied the time tables with the Herren, making

his travel plans, giving exact instructions for the next meeting.

As he left his office it was with the conviction that his affairs

were in order.

He took a hired car and drove back to

Lendenich, confident and self-assured. It was only as the servant

opened the gate for him, as he walked across the courtyard and up

the steps of the mansion, it was only then that his confidence left

him.

He searched for Alraune and took it as a good

omen that no guests were there. He heard from the maid that she had

dined alone and was now in her rooms so he went up there. He

stepped inside at her, ‘Come in.’

“I must speak with you,” he said.

She sat at her writing desk, looked up

briefly.

“No,” she cried. “I don’t want to right

now.”

“It is very important,” he pleaded. “It is

urgent.”

She looked at him, lightly crossed her

feet.“Not now,” she answered. “–Go down–in a half hour.”

He went, took off his fur coat, sat down on

the sofa and waited. He considered how he should tell her, weighed

every sentence and every word. After a good hour he heard her

steps.

He got up, went to the door–there she stood

in front of him, as an elevator boy in a tight fitting strawberry

red uniform.

“Ah,” he said, “that is kind of you.”

“Your reward,” she laughed. “Because you have

obeyed so beautifully today–now tell me, what is it?”

The Privy Councilor didn’t gloss things over,

he told her everything, like it was, each little detail without any

embellishments. She didn’t interrupt, let him speak and

confess.

“It is really your fault,” he said. “I would

have taken care of it all without much trouble–but I let it all go,

have been so preoccupied with you, they grew like the heads of the

Hydra.”

“The evil Hydra”–she mocked, “and now she is

giving poor, good Hercules so much trouble! By the way, it seems

that this time the hero is a poisonous salamander and the monstrous

Hydra is the punishing avenger.”

“Certainly,” he nodded, “from the viewpoint

of the people. They have their ‘justice for everyone’ and I have

made my own. That is really my only crime. I believed that you

would understand.”

She laughed in delight, “Certainly daddy, why

not? Am I reproaching you? Now tell me, what are you going to

do?”

He proposed his plans to her, one after the

other, that they had to flee, that very night–take a little trip

and see the world. Perhaps first to London, or to Paris–they could

stay there until they got everything they needed. Then over the

ocean, across America–to Japan–or to India–whatever they wanted,

even both, there was no hurry. They had time enough. Then finally

to Palestine, to Greece, Italy and Spain. Where ever she

wanted–there they could stay and leave again when they had enough.

Finally they could buy a villa somewhere on Lake Garda or on the

Riviera. Naturally it would be in the middle of a large garden.

She could have her horses and her cars, even

a yacht. She could fill the entire house with people if she

wanted–

He wasn’t stingy with his promises, painted

in glowing colors all the tempting splendors that awaited her, was

always finding new and more alluring reasons that she should

go.

Finally he stopped, asked his question, “Now

child, what do you say to that? Wouldn’t you like to live like

that?”

She sat on the table with her slender legs

dangling.

“Oh yes,” she nodded. “Very much

so–only–only–”

“Only?”–he asked quickly. “If you wish

something else–say it! I will fulfill it for you.”

She laughed at him, “Well then, fulfill this

for me! I would very much like to travel–only not with you!”

The Privy Councilor took a step back, almost

fell, grabbed onto the back of a chair. He searched for words and

found none.

She spoke, “With you it would be boring for

me–you are tiresome to me–I want to go without you!”

He laughed, attempting to persuade himself

that she was joking.

“But I am the one that must be leaving right

away,” he said. “I must leave–tonight yet!”

“Then leave,” she said quietly. “I’m

staying.”

He began all over again, imploring and

lamenting. He told her that he needed her, like the air that he

breathed. She should have compassion on him–soon he would be eighty

and wouldn’t be a burden to her very much longer.

Then he threatened her again, screamed that

he would disinherit her, throw her out into the street without a

penny.

“Just try it,” she threw back at him.

He spoke yet again, painting the wonderful

splendors that he wanted to give her. She should be free, like no

other girl, to do and have as she desired. There was no wish, no

thought that he couldn’t turn into reality for her. She only had to

come with–not leave him alone.

She shook her head. “I like it here. I

haven’t done anything–I’m staying.”

She spoke quietly and calmly, never

interrupted him, let him talk and make promises, start all over

again. But she shook her head whenever he asked the question.

Finally she sprang down from the table and

went with soft steps toward the door, passing him.

“It is late,” she said. “I am tired. I’m

going to bed–good night daddy, happy travels.”

He stepped into her way, made one last

attempt, sobbed out that he was her father, that children had a

duty to their parents, spoke like a pastor.

She laughed at that, “So I can go to

heaven!”

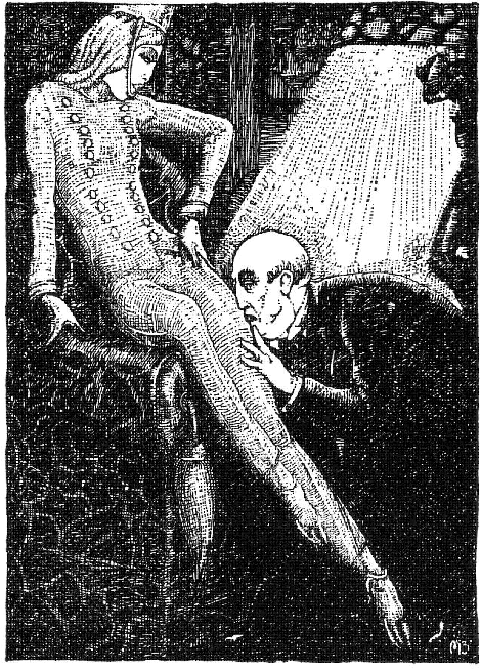

She stood near the sofa, set down astride the

arm.

“How do you like my leg?” she cried suddenly

and stretched her slender leg out toward him, moving it back and

forth in the air.

He stared at her leg, forgot what he wanted,

thought no more about flight or danger, saw nothing else, felt

nothing–other than her slender strawberry red boy’s leg that swung

back and forth before his eyes.

“I am a good child,” she tittered. “A very

dear child that makes her stupid daddy very happy–kiss my leg,

daddy–caress my beautiful leg daddy!”

He fell heavily onto his knees, grabbed at

her red leg, moved his straying fingers over her thigh and her

tight calf, pressed his moist lips on the red fabric, licked slowly

along it with his trembling tongue.

Then she sprang up, lightly and nimbly,

tugged on his ear, and patted him softly on the cheek.

“Now daddy,” her voice tinkled, “have I

fulfilled my duty well enough? Good night then! Happy travels–and

don’t get caught–it would be very unpleasant in prison. Send me

some pretty picture postcards, you hear?”

She was at the door before he could get up,

made a bow, short and stiff like a boy and put her right hand to

her cap.

He forgot what he wanted, thought no more

about flight or danger

“It has been an honor, your Excellency,” she

cried. “And don’t make too much noise down here while you are

packing–it might disturb my sleep.”

He swayed towards her, saw how quickly she

ran up the stairs. He heard the door open upstairs, heard the latch

click and the key turn in it twice. He wanted to go after her, laid

his hand on the banister. But he felt that she would not open,

despite all his pleading. That door would remain closed to him even

if he stood there for hours through the entire night until dawn,

until–until–until the constable came to take him away.

He stood there unmoving, listening to her

light steps above him, back and forth through her room. Then no

more. Then it was silent.

He slipped out of the house, went bare headed

through the heavy rain across the courtyard, stepped into the

library, searched for matches, lit a couple of candles on his desk.

Then he let himself fall heavily into his easy chair.

Who is she,” he whispered. “What is she? What

a creature!” he muttered.

He unlocked the old mahogany desk, pulled a

drawer open, took out the leather bound volume and laid it in front

of him.

He stared at the cover, “A.T. B.”, he read,

half out loud. “Alraune ten Brinken.”

The game was over, totally over, he sensed

that completely. And he had lost – he held no more cards in his

hand. It had been his game; he alone had shuffled the cards. He had

held all the trumps–and now he had lost anyway.