Hanns Heinz Ewers Alraune (32 page)

Read Hanns Heinz Ewers Alraune Online

Authors: Joe Bandel

Tags: #alraune, #decadence, #german, #gothic, #hanns heinz ewers, #horror, #literature, #translations

He smiled grimly, now he had to pay the

price.

Pay the price? Oh yes, but in what coin?

He looked at the clock–it was past twelve.

The people would come with the warrant around seven o’clock at the

latest–he still had over six hours. They would be very considerate,

very polite–they would even bring him into custody in his own car.

Then–then the battle would begin. That would not be too bad–he

would defend himself through several months, dispute every move his

opponents made.

But finally–in the main case–he would lose

anyway. Manasse had that right. Then it would be–prison–or flee–but

alone. Entirely alone? Without her? In that moment he felt how he

hated her, but he also knew as well that he could think of nothing

else any more, only her. He could run around the world aimlessly,

without purpose, not seeing, not hearing anything but her bright

twittering voice, her slender swinging red leg.

Oh, he would starve, out there or in

prison–either way. Her leg–her sweet slender boy’s leg! Oh how

could he live without that red leg?

The game was lost–he must pay the bill,

better to pay it quickly, this very night–with the only thing of

value he had left–with his life. And since it wasn’t worth anything

any more, perhaps he could bring someone else down with him.

That did him good, now he brooded about whom

to take down with him. Someone that would give him a little

satisfaction to give one final last kick.

He took his last will and testament out of

the desk, which named Alraune as his heir, read through it, then

carefully tore it into small pieces.

“I must make a new one,” he whispered. “Only

for whom?–for whom?”

There was his sister–was her son, Frank

Braun, his nephew–

He hesitated, him–him? Wasn’t it him that had

brought this poisonous gift into his house, this strange creature

that had now ruined him?

He–just like the others! Oh, he should pay,

even more than Alraune.

“You will tempt God,” the fellow had said.

“You will put a question to him, so audacious that He must

answer.”

Oh yes, now he had his answer! But if he

inexorably had to go down, the youth should share his fate. He,

Frank Braun, who had engendered this thought, given him the

idea.

Now he had a bright shiny weapon, her, his

little daughter, Alraune ten Brinken. She would bring him as well

to the point where he was today. He considered, rocked his head and

grinned in satisfaction at this certain final victory.

Then he wrote his will without pausing, in

swift, ugly strokes. Alraune remained his heir, her alone. But he

secured a legacy for his sister and another for his nephew, whom he

appointed as executor and guardian of the girl until she came of

age. That way he needed to come here, be near her, breathe the

sultry air from her lips, and it would happen, like it had happened

with all the others!

Like it had with the Count and with Dr.

Mohnen, like it had with Wolf Gontram, like with the chauffeur–and

finally, like it had happened with he, himself, as well.

He laughed out loud, made still another

entry, that the university would inherit if Alraune died without an

heir. That way his nephew would be shut out in any case. Then he

signed the document and dated it.

He took the leather bound volume, read

further, wrote the early history and conscientiously brought

everything up to date. He ended it with a little note to his

nephew, dripping with derision.

“Try your luck,” he wrote. “To bad that I

won’t be there when your turn comes. I would have been very glad to

see it!”

He carefully blotted the wet ink, closed the

book and laid it back in the drawer with the other momentos, the

necklace of the Princess, the alraune of the Gontrams, the dice

cup, the white card with a hole shot through it that he had taken

out of the count’s vest pocket. “Mascot” was written on it. Near it

lay a four leaf clover–several black drops of clotted blood still

clung to it–

He stepped up to the curtain and untied the

silk cord. With a long scissors he cut the end off and threw it

into the drawer with the others. “Mascot’, he laughed. “Luck for

the house!”

He searched around the walls, climbed onto a

chair and with great difficulty took down a mighty iron cross from

a heavy hook, laid it carefully on the divan.

“Excuse me,” he grinned, “for moving you out

of your place–it will only be for a short time–only for a few

hours–you will have a worthy replacement!”

He knotted the cord, threw it high over the

hook, pulled on it, considered it, that it would hold–and he

climbed for a second time onto the chair–

The police found him early the next morning.

The chair was pushed over; nevertheless the dead man stood on it

with the tip of one toe. It appeared as if he had regretted the

deed and at the last moment tried to save himself. His right eye

stood wide open, squinting out toward the door and his thick blue

tongue protruded out–he looked very ugly.

Perhaps your quiet days, my blonde little

sister, will also drop like silver bells that ring softly with

slumbering sins.

Laburnums now throw their poisonous yellow

where the pale snow of the acacias once lay. Ardent clematis show

their deep blue where the devout clusters of wisteria once

peacefully resounded.

Sweet is the gentle game of lustful desire;

yet sweeter to me are all the cruel raging passions of the

nighttime. Yet sweeter than any of these to me now is sweet

sleeping sin on a hot summer afternoon.

–

She slumbers lightly, my gentle

companion, and I dare not awaken her. She is never more beautiful

than when she is sleeping like this. In the mirror my darling sin

rests, near enough, resting in her thin silken shift on white

linen.

Your hand, little sister, falls over the edge

of the bed. Your slender finger that carries my gold band is gently

curling. Your transparent rosy nails glow like the first light of

morning. Fanny, your black maid, manicured them. It was she that

created these little marvels.

And I kiss your marvelous transparent rosy

nails in the mirror.

Only in the mirror–in the mirror only. Only

with loving glances and the light touch of my lips.

They will grow, if sin awakes, they will

grow, become the sharp claws of a tiger, tearing my flesh–

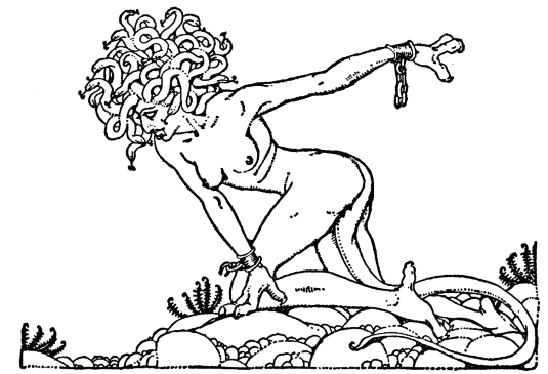

Your head rises out of the pillow, surrounded

by golden locks. They fall around it lightly like flickering golden

flames that awaken at the first breezes of early morning. Your

little teeth smile out from your thin lips, like the milky opals in

the glowing bracelet of the moon Goddess.

And I kiss your golden hair, sister, and your

gleaming teeth–in the mirror–only in the mirror. With the soft

touch of my lips and with loving glances.

For I know that if ardent sin awakes the

milky opals become mighty fangs and the golden locks become fiery

vipers. Then the claws of the tigress tear at my flesh, the sharp

teeth bite dreadful, bloody wounds. Then the flaming vipers hiss

around my head, crawl into my ears, spray their venom into my

brain, whisper and entice with a fairy tale of savage lust–

Your silken shift has fallen down from your

shoulder, your childish breasts smile there, resting, like two

white newborn kittens, lifting their sweet rosy noses into the

air.

I look up at your gentle eyes, jeweled blue

eyes that catch the light, that glow like the sapphire on the

forehead of my golden Buddha figurine.

Do you see, sister, how I kiss them–in the

mirror? No fairy has a lighter touch.

–

For I know well, when she wakes up, my

eternal sin, blue lightening will flash out of her eyes. It will

strike my poor heart, making my blood boil and seethe, melting in

ardent desire the strong chains that restrain me, till all becomes

madness and then surges the entire–

Then hunts, free of her chains, the raging

beast. She overpowers you, sister, in furious frenzy. Your sweet

childish breasts become the giant breasts of a murderous fury–now

that sin has awakened–she rends in joy, bites in fury, exults in

pain and bathes in pools of blood.

But my glances are still silent, like the

tread of nuns at the grave of a saint. Softer yet is the light

touch of my lips, like the kiss of the Holy Ghost at communion that

turns the bread into the body of our Lord.

She should not awaken, should remain

peacefully sleeping–my beautiful sin.

Nothing, my love, is sweeter to me, than pure

sin as you lightly sleep.

Gives an account of how Frank Braun stepped

into Alraune’s world.

F

RANK

Braun had come back to his mother’s house,

somewhere from one of his aimless journeys, from Cashmir in Asia or

from Bolivian Chaco. Or perhaps is was from the West Indies where

he had played revolutionary in some mad republic, or from the South

Seas, where he had dreamed fairytales with the slender daughters of

a dying race. He came back from somewhere.

Slowly he walked through his mother’s house,

up the white staircase upon whose walls was pressed frame upon

frame, old engravings and modern etchings, through his mother’s

wide rooms in which the spring sun fell through yellow curtains.

There his ancestors hung, many Brinkens with sharp and clever

faces, people that knew where they stood in the world.

There was his great-grandfather and

great-grandmother–good portraits from the time of the Emperor, then

one of his beautiful grandmother–sixteen years old, in the earlier

dress of Queen Victoria. His father and mother hung there and his

own portraits as well. There was one of him as a child with a large

ball in his hands and long blonde child locks that fell over his

shoulders. The other was of him as a youth, in the black velvet

dress of a page, reading in a thick, ancient tome.

In the next room were the copies. They came

from everywhere, from the Dresden Gallery, the Cassel and

Braunshweig galleries, from the Palazzo Pitti, the Prado and from

the Reich Museum. There were many Dutch masters, Rembrandt, Frans

Hals, Ostade, Murillo, Titian, Velasquez and Veronese. All were a

little darkened with age, but they glowed reddish gold in the

sunlight that broke through the curtains.

He went further, through the room where the

modernists hung. There were several good paintings and some not as

good. But not one of them was bad and there were no sweet ones.

All around stood old furniture, most of

mahogany–Empire, Directoire or Biedermeir. There were none of oak

but several simpler, modern pieces were scattered in between. There

was no defined style, simply one after another as the years had

brought them. Yet there was a quiet, pervasive harmony that

transformed everything that stood there and made it belong.

He climbed up to the floor that his mother

had given him. Everything was exactly as he had left it the last

time he had departed–two years ago. No paperweight had been moved,

no chair was out of place. Yes, his mother always watched to see

that the maids were careful and respectful–despite all the cleaning

and dusting.

Here, much more than anywhere else in the

house, ruled a chaotic throng of innumerable, abstruse things. They

were on the floors and on the walls. Five continents contributed

strange and bizarre things to this room that were unique to them

only.

There were large masks, savage wooden devil

deities from the Bismarck Archipelago, Chinese and Annamite flags

and many weapons from all regions of the world. Then there were

hunting trophies, stuffed animals, Jaguar and tiger skins, huge

turtle shells, snakes and crocodiles. There were colorful drums

from Luzon, long necked stringed instruments from Raj Putana and

crude castings from Albania.

On one wall hung a mighty, reddish brown

fisherman’s net. It hung down from the ceiling and contained giant

star fish, sea urchins, swords from swordfish, silver shimmering

tarpon scales, mighty ocean spiders, strange deep-sea fish, mussels

and snails.