Happy Accidents: Serendipity in Major Medical Breakthroughs in the Twentieth Century (3 page)

Read Happy Accidents: Serendipity in Major Medical Breakthroughs in the Twentieth Century Online

Authors: Morton A. Meyers

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Reference, #Technology & Engineering, #Biomedical

By dipping into the world of art, and especially into visual illusions, scientists can gain perspective on illusions of judgment, also known as cognitive illusions. Gestalt psychologists have elaborated on such things as the balances in visual perception between foreground and background, dark and light areas, and convex and concave contours. The gist of their message is that too-close attention to detail may obscure the view of the whole—a message with special meaning for those alert to serendipitous discovery.

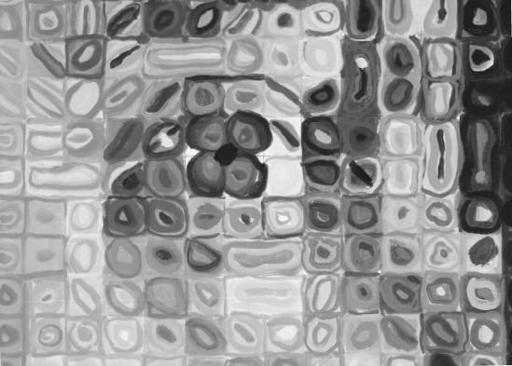

To readily appreciate this phenomenon, consider the paintings of the contemporary artist Chuck Close. Viewed at the usual distance, they are seen as discrete squares of lozenges, blips, and teardrops.

Detail from Chuck Close's

Kiki

—left eye.

Viewed from a much greater distance, they can be appreciated as large, lifelike portraits.

Chuck Close,

Kiki

, 1973. Oil on canvas, 100 x 84 in. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

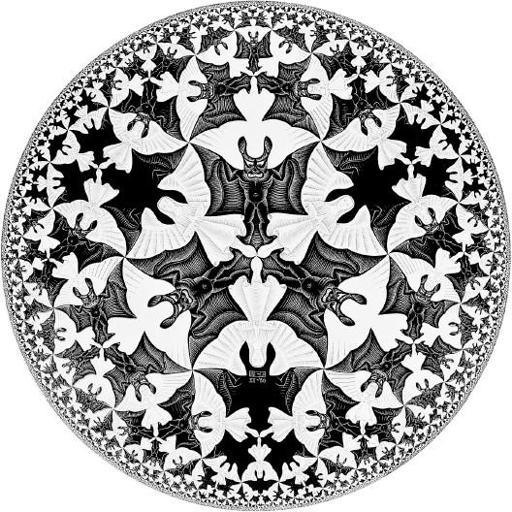

In a Gestalt figure, such as the M. C. Escher drawing on the next page, one can see the devils or the angels, but not both at the same

time. Even after you know that there is more than one inherent pattern, you see only one at a time; your perception excludes the others.

M. C. Escher,

Circle Limit IV

, 1960. Woodcut in black and ochre, printed from two blocks.

The same holds true for W. E. Hill's

My Wife and My Mother-in-Law.

It's easy to see his dainty wife, but you have to alter your whole way of making sense of the lines to see the big-nosed, pointy-chinned mother-in-law.

Certainly, if one's perspective is too tightly focused, gross distortion may result. This phenomenon has broad implications for medical research. So does the human tendency to believe that one's partial

view of an image—or, indeed, a view of the world—captures its entirety. We often misjudge or misperceive what is logically implied or actually present. In drama this may lead to farce, but in science it leads to dead ends.

W. E. Hill,

My Wife and My Mother-in-Law

, 1915.

Illustrative of this phenomenon are poet John Godfrey Saxe's six blind men (from his poem “The Blind Men and the Elephant”)

observing different parts of an elephant and coming to very different but equally erroneous conclusions about it. The first fell against the elephant's side and concluded that it was a wall. The second felt the smooth, sharp tusk and mistook it for a spear. The third held the squirming trunk and knew it was a snake. The fourth took the knee to be a tree. The fifth touched the ear and declared it a fan. And the sixth seized the tail and thought he had a rope. One of the poem's lessons: “Each was partly in the right, And all were in the wrong!”

12

Robert Park, a professor of physics at the University of Maryland and author of

Voodoo Science,

recounts an incident that showed how expectations can color perceptions. It happened in 1954 when he was a young air force lieutenant driving from Texas into New Mexico. Sightings of UFOs in the area of Roswell, New Mexico, were being reported frequently at the time.

I was driving on a totally deserted stretch of highway…. It was a moonless night but very clear, and I could make out a range of ragged hills off to my left, silhouetted against the background of stars…. It was then that I saw the flying saucer. It was again off to my left between the highway and the distant hills, racing along just above the range land. It appeared to be a shiny metallic disk viewed on edge—thicker in the center—and it was traveling at almost the same speed I was. Was it following me? I stepped hard on the gas pedal of the Oldsmobile—and the saucer accelerated. I slammed on the brakes—and it stopped. Then I could see that it was only my headlights, reflecting off a single phone line strung parallel to the highway. Suddenly, it no longer looked like a flying saucer at all.

13

People, even scientists, too often make assumptions about what they are “seeing,” and seeing is often a matter of interpretation or perception. As Goethe said, “We see only what we know.” As they seek causes in biology, researchers can become stuck in an established mode of inquiry when the answer might lie in a totally different direction that can be “seen” only when perception is altered. “Discovery

consists of seeing what everybody has seen and thinking what nobody has thought,” according to Nobelist Albert Szent-Györgyi.

14

Another trap for scientists lurks in the common logical fallacy

post hoc, ergo propter hoc—

the faulty logic of attributing causation based solely on a chronological arrangement of events. We tend to attribute an occurrence to whatever event preceded it: “After it, therefore because of it.”

Consider Frank Herbert's story from

Heretics of Dune:

There was a man who sat each day looking out through a narrow vertical opening where a single board had been removed from a tall wooden fence. Each day a wild ass of the desert passed outside the fence and across the narrow opening—first the nose, then the head, the forelegs, the long brown back, the hindleg and lastly the tail. One day, the man leaped to his feet with the light of discovery in his eyes and he shouted for all who could hear him: “It is obvious! The nose causes the tail!”

15

A real-life example of this type of fallacy, famous in medical circles, occurred in the case of the Danish pathologist Johannes Fibiger, who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1926 for making a “connection” that didn't exist. Fibiger discovered roundworm parasites in the stomach cancers of rats and was convinced that he had found a causal link. He believed that the larvae of the parasite in cockroaches eaten by the rats brought about the cancer, and presented experimental work in support of this theory. Cancer research at this time was inhibited by the lack of an animal model. The Nobel committee considered his work “the greatest contribution to experimental medicine in our generation.” His results were subsequently never confirmed and are no longer accepted.

Another, less famous example of false causality occurred in New York in 1956. A young physicist, Chen Ning Yang, and his colleague, Tsung-Dao Lee, were in the habit of discussing apparent inconsistencies involving newly recognized particles coming out of accelerators while relaxing over a meal at a Chinese restaurant on 125th Street in

Manhattan frequented by faculty and students from Columbia University. One day the solution that explained one of the basic forces in the atom suddenly struck Yang, and within a year the two shared one of the quickest Nobel Prizes (in Physics) ever awarded. After the award was announced, the restaurant placed a notice in the window proclaiming “Eat here, get Nobel Prize.”

16

P

ATHWAYS OF

C

REATIVE

T

HOUGHT

Researchers and creative thinkers themselves generally describe three pathways of thought that lead to creative insight: reason, intuition, and imagination.

Three Pathways of Creative Thought

Reason | Intuition | Imagination |

Logic | Informal patterns of expectation | Visual imagery born of experience |

While reason governs most research endeavors, the most productive of the three pathways is intuition. Even many logicians admit that logic, concerned as it is with correctness and validity, does not foster productive thinking. Einstein said, “The really valuable factor is intuition…. There is no logical way to the discovery of these elemental laws. There is only the way of intuition, which is helped by a feeling for the order lying behind the appearance.”

17

The order lying behind the appearance:

this is what so many of the great discoveries in medicine have in common. Such intuition requires asking questions that no one has asked before. Isidor Rabi, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist, told of an early influence on his sense of inquiry. When he returned home from grade school each day, his mother would ask not “Did you learn anything today?” but “Did you ask a good question today?”

18

Gerald Edelman, a Nobel laureate in medicine, affirms that “the asking of the question is the important

thing…. The idea is: can you ask the question in such a way as to facilitate the answer? And I think really great scientists do that.”

19

Intuition is not a vague impulse, not just a “hunch.” Rather, it is a cognitive skill, a capability that involves making judgments based on very little information. An understanding of the biological basis of intuition—one of the most important new fields in psychology—has been elaborated by recent brain-imaging studies. In young people who are in the early stages of acquiring a new cognitive skill, the right hemisphere of the brain is activated. But as efficient pattern-recognition synthesis is acquired with increasing age, activation shifts to the left hemisphere. Intuition, based upon long experience, results from the development in the brain of neural networks upon which efficient pattern recognition relies.

20

The experience may come from deep in what has been termed the “adaptive unconscious” and may be central to creative thinking.

21

As for imagination, it incorporates, even within its linguistic root, the concept of visual imagery; indeed, such words and phrases as “insight” and “in the mind's eye” are derived from it. Paul Ehrlich, who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1908 for his work on immunity, had a special gift for mentally visualizing the three-dimensional chemical structure of substances. “Benzene rings and structural formulae disport themselves in space before my eyes…. Sometimes I am able to foresee things recognized only much later by the disciples of systemic chemistry.”

22

Other scientists have displayed a similar sort of talent leading to breakthroughs in understanding structures.