Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man (20 page)

Read Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man Online

Authors: Mark Changizi

Tags: #Non-Fiction

Melodic contours are, in the sights of this movement theory of music, about the sequence of movement directions of a fictional mover. When the melody’s pitch changes, the music is narrating to your auditory system that the depicted mover is changing his or her direction of movement. If this really

is

what melody means, then melody and people should have similar

turning

behavior.

How quickly

do

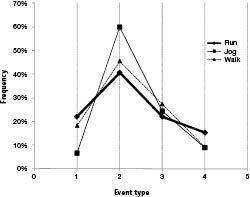

people turn when moving? Get on up and let’s see. Walk around and make a turn or two. Notice that when you turn 90 degrees, you don’t usually take 10 steps to do so, and you also don’t typically turn on a dime. In order to get a better idea of how quickly people tend to change direction, I set out to find videos of people moving and changing direction. After some thought, undergraduate RPI student Eric Jordan and I eventually settled on videos of soccer players. Soccer was perfect because players commonly alter their direction of movement as the ball’s location on the field rapidly changes. Soccer players also exhibit the full range of human speeds, allowing us to check whether turning rate depends on speed. Eric measured 126 instances of approximately right-angle turns, and in each case, recorded the number of steps the player took to make the turn. Figure 29 shows the distribution for the number of steps taken. As can be seen in the figure, these soccer players typically took two steps to turn 90 degrees, and this was the case whether they were walking, jogging, or running. Casual observation of movers outside of soccer games—such as in coffee shops—suggests that this is not a result peculiar to soccer.

If music sounds like human movers, then it should be the case that the depicted mover in music turns at rates typical for humans. Specifically, then, we expect the musical mover to take a right-angle turn in about two steps on average. What does this mean musically? A step in music is a beat, and so the expectation is that music will turn 90 degrees in about two beats. But what does it mean to “turn 90 degrees” in music?

Recall that the maximum pitch in a song means the mover is headed directly toward the listener, and the lowest pitch means the mover is headed directly away.

That

is a 180-degree difference in mover direction. Therefore, when a melody moves over the entirety of the

tessitura

(the melody’s pitch range), it means that the depicted mover is changing direction by 180 degrees (either from toward you to away from you, or vice versa). And if the melody spans just the top or bottom half of the tessitura, it means the mover has turned 90 degrees. Because human movers take about two steps to turn 90 degrees—as we just saw—we expect that melodies tend to take about two beats to cross the upper or lower half of the tessitura.

Figure 29

. Distribution of the number of footsteps soccer players take to turn 90 degrees, for walkers, joggers, and runners. The average number of footsteps for a right-angle turn for walkers is 2.16 (SE 0.17, n=22); for joggers, 2.21 (SE 0.11, n=45); and for runners, 2.23 (SE 0.13, n=59).

To test this, we measured from the

Dictionary of Musical Themes

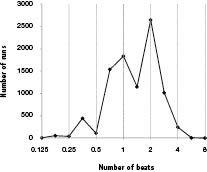

melodic “runs” (i.e., strictly rising or strictly falling sequences of notes) having at least three notes within the upper or lower half of the tessitura (and filling at least 80 percent of the width of that half tessitura). These are among the clearest potential candidates for 90-degree turns in music. Figure 30 shows how many beats music typically takes to do its 90-degree turns. The peak is at two beats, consistent with the two footsteps of people making 90-degree turns while moving. Music turns as quickly as people do!

Figure 30

. Distribution of the number of beats for a theme “run” to cover the top or bottom half of the tessitura. The most common number of beats to cross half the tessitura is two, consistent with how quickly people turn 90 degrees. (Runs had three or more notes moving in the same direction, and all within the top or bottom half of the tessitura, and filling at least 80% of its half tessitura.)

This close fit between human and melodic turning rates is, as we will see, helpful in trying to understand regularities in the overall structure of melody, which we delve into next.

Musical Encounters

In light of the theory that music is a story about a fictional mover in our midst, is it possible to address what a typical melody is like? How do melodies usually begin? What is the typical melodic contour shape? How many beats are in a typical melody? Is there even such a thing as a “typical” melody?

To answer whether there is a typical melody, we must ask if there is a typical way in which a mover moves in our midst. Is there such a thing as a typical story of human movement?

Yes, in fact, there is. In a nutshell, the most generic possible story of a human mover consists of the mover noticing you and veering toward you, interacting with you in some way, and then scampering off. The plot is: “Hello. How are you? Good-bye.” Let’s call this an “encounter.” Stories told by composers by no means must be encounters, of course. One can expect to find tremendous variability in the stories told by music. But there is no getting around the fact that Hello–HowAreYou–Good-bye is a common story, whereas, say, Good-bye–Hello–HowAreYou is a strange story. People in stories usually arrive and

then

depart, not vice versa.

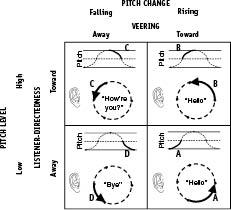

If “encounters” are indeed the most typical story of human movement in our midst, then let’s be more specific about the kinds of movement involved. Figure 31 shows the four qualitatively distinct kinds of movement we discussed earlier in the chapter. Can we say what an encounter is in terms of these movement categories? Yes. In the “Hello” part of the encounter, the mover suddenly notices you and begins veering toward you. This is case A or B in Figure 31, depending on whether the mover was receding or nearing, respectively, when he first noticed you. If A is the start of the story, then B occurs next. By the end of B, the mover has gotten near enough that he must begin veering away, lest he bump into you. This is the segment of the mover’s path that brings him closest to you—where he says, “How are you?”—and is case C in Figure 31. Finally, in the “Good-bye” part of the encounter, the mover veers away, which is case D.

Figure 31

. Summary of the movement meaning of pitch for low and high, rising and falling pitch, as shown earlier in Figure 28. The sequence A-B-C-D is a plausible “most generic” movement, which I call an “encounter,” or Hello–HowAreYou–Good-bye movement.

The generic encounter, then, has one of two sequences, B-C-D or A-B-C-D, with the movement meanings of A through D defined in Figure 31. Furthermore, I suggest that the “full” A-B-C-D movement is the more common of the two, because stories of human movement often consist of multiple, repeated encounters, and in these cases A will be the first segment of any encounter after the first. That is to say, if a mover goes away, then turns to come back for another encounter, the sequence must begin at A, not B. We conclude, then, that the generic Hello–HowAreYou–Good-bye movement is thus A-B-C-D. A-B is the “Hello.” C is the “How are you?” And D is the “Good-bye.”

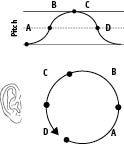

We now have some idea of what a generic movement is, and so the next question is, “What does it sound like?” With Figure 31 in hand, we can immediately say what the Doppler pitches are for this movement. Figure 32 illustrates the overhead view and the pitch contour of the generic A-B-C-D encounter. This generic pitch contour in Figure 32 has two distinctive features that we expect, no matter the specific shape of the mover’s encounter path. First and foremost, the generic pitch contour goes up, and then down. Second, it dwells longer (has a flatter slope) at the minimum and maximum of its pitch range (something I will discuss in the Encore section titled “Home Pitch”). In essence, this pitch contour shares two qualitative features that are crucial to

hills

: hills are not just lumps of earth on the ground—not domes, not mounds, not pyramids, not wedges—but have gentle slopes toward their bottoms and a gentle flattening at the top.

Figure 32

. The most generic sequence of movement, and its pitch over time. One can see it is a “hill.” Furthermore, this path tends to be traversed in around eight steps (because people tend to take about two steps to turn 90 degrees).

We are nearly ready to ask whether melodies tend to look like the “hill” we see in the pitch contour of the generic encounter, but first we must gather one further piece of information about encounters. We need to know how long an encounter lasts. When movers do a Hello–HowAreYou–Good-bye to us, do they do it over 100 footsteps, or four? Our results from the previous section (“Human Curves”) can help us answer. We saw then that human movers tend to take about two steps to turn 90 degrees. Each of the four segments of the generic encounter—A, B, C, and D—is roughly a 90-degree turn, and thus the entire encounter can be carried out in about eight steps. Although Hello–HowAreYou–Good-bye behaviors can take fewer or more than eight footsteps, a plausible baseline expectation is that generic encounters will occupy around eight steps—not two steps, and not 80. The generic story of human movement in our midst—the “encounter”—is not just the sequence of movements A-B-C-D, but also, these movements being enacted in eight or so steps. Accordingly, the generic Doppler pitch contour is not just a hill, but a hill implemented in about eight footsteps. The sound of a generic human mover in our midst is an eight-step pitch hill.