Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip (23 page)

Read Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip Online

Authors: Matthew Algeo

Tags: #Presidents & Heads of State, #Presidents, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues, #General, #United States, #Automobile Travel, #Biography & Autobiography, #20th Century, #History

The General Assembly happened to be in session, and the secretary general was delivering a report. I couldn’t figure out what it was about, but it sounded dreadfully dull. The hall was less than half full. Some of the delegates appeared to be dozing. It seemed no more exciting than the average city council meeting—and considerably less exciting than one in, say, Philadelphia or Chicago.

And that was it. Julia led us outside, let her hair down again, and delivered a short soliloquy in which she stressed that the UN was not a governmental organ-eye-zation. She ended with a quote from Kofi Anan, who was once asked why God was able to create the world in seven days while it has taken the UN more than sixty years to achieve what it has.

“The good Lord,” replied Anan, “had the advantage of working alone.”

The next day was the Fourth of July. Harry and Bess celebrated by catching another show, the matinee performance of the play

My Three Angels

at the Morosco Theater on 45th Street. (The theater, where both

Death of a Salesman

and

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

opened, was demolished in 1982 to make way for a Marriott hotel.) That night they had a quiet dinner at the Waldorf and went to bed early. It had been a whirlwind week. It was time to go home.

Pennsylvania (or, Abducted),

July 5–6, 1953

T

he Automobile Club of New York predicted a record-breaking one million cars would be on the city’s highways over the Fourth of July weekend in 1953. (The auto club also predicted a record-breaking number of highway fatalities, prompting this jolly headline in the

New York World-Telegram and Sun:

“Hundreds to Die as Nation Observes Independence Day.”) To get a jump on the holiday traffic, Harry and Bess got up before dawn on Sunday, July 5. Two bellhops helped Harry carry their luggage down to the garage, but Harry loaded it all into the car by himself, despite the bellhops’ protestations.

“I’ll go back up and get the folks for breakfast,” Harry announced after all the bags were stowed to his satisfaction.

A few minutes later, Harry, Bess, and Margaret entered the hotel’s Norse Grill.

Harry and Bess pulling away from the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, July 5, 1953. Margaret is in the back seat. Harry dropped her off at her apartment before heading for home.

“He ordered a half grapefruit, toast, coffee, and bacon,” the

New York Times

solemnly reported. “The women ordered cantaloupe.”

After breakfast, the family posed for photographs at the garage entrance, and Harry gave his autograph to two youngsters. When asked which way he planned to drive home, Harry was cagy. “It’ll be a zigzag route,” was all he would say.

It was seven o’clock now, and Harry was eager to hit the road.

“This has been a happy week,” he told the reporters and photographers who’d come to chronicle his departure. He and Bess had had so much fun, he said, “it makes it so we want to come back.”

Then he and Bess and Margaret climbed into the big black Chrysler.

“Well, let’s go!” he said.

He pulled out of the Waldorf garage and turned right onto 49th Street. At Madison Avenue he turned right again. At 76th Street he parked in front of the Carlyle, where Margaret lived. Bess asked Margaret, probably for the millionth time, if she was sure she didn’t want to ride back to Independence with her parents. Yes, said Margaret with a smile. She was much too busy in New York to go home just then.

Bess waited in the car while Harry and Margaret went inside. In the lobby Harry kissed his daughter good-bye.

Emerging from the hotel, Harry asked a passerby, “Say, where is this West Side Highway?” He planned to take the highway to the Holland Tunnel.

“Are you really Mr. Truman?” said the perplexed pedestrian. Truman laughed, admitted he was, and got his directions.

They pulled onto the highway at 57th Street and headed north—the wrong direction. A newspaper photographer named Tom Gallagher who was following the Trumans realized their mistake. He caught up with them at 72nd Street and got them turned around.

It was 7:40 by the time the Trumans arrived at the entrance to the Holland Tunnel, where the toll taker recognized Harry and shook his hand before taking his fifty cents.

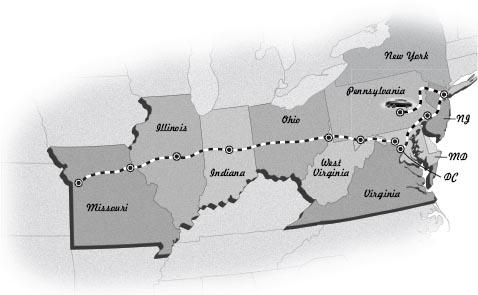

Emerging in New Jersey, they took the Pulaski Skyway to Newark, where Harry picked up Highway 22 and headed west, toward Pennsylvania, disappearing into the growing crush of traffic, just another holiday motorist.

Shortly before noon, Harry pulled into a service station on the east side of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. One of the attendants, Herbert Zearing, was cleaning the windshield when he realized who his customer was. “I kept working because I didn’t want to look surprised,” said Zearing. Meanwhile, the other attendant, Lester Lingle Jr., filled the car with 11.1 gallons of premium gasoline. The bill came to $3.45. Harry paid with a twenty. Bess, as she had throughout the trip, dutifully logged the purchase.

After filling up, Harry drove through downtown Harrisburg, past the green-domed capitol, where, according to one account, “one middle-aged man pointed excitedly at the Truman car as he gaped after the driving ex-president.” He crossed the Susquehanna River, picked up Highway 11, and continued west.

In the town of New Kingstown, just a few miles west of Harrisburg, the Trumans passed a small white building surrounded by a dazzling sea of flowers in full bloom. This caught Bess’s eye. “Harry, turn around,” she said. “Go back. I want to see that.” Harry did as Bess asked. The building was a restaurant called the Country House. They got out to admire the flowers. Then, since they were hungry anyway, they went inside for lunch.

They were seated and ordered two large fruit bowls. At first, nobody recognized them, even after they chatted with several other customers.

But one of the cooks had his suspicions. He went out to the parking lot. When he saw the Missouri plates on the big black Chrysler the couple was driving, his suspicions were confirmed. “The place became very excited after that,” said the next day’s

Harrisburg Patriot,

“and everybody asked for autographs.”

The building that housed the Country House is now the New Kingstown post office. I went inside. It looked exactly like every other small town post office, with a small counter and a wall of PO boxes. There was nothing distinctive about it. It was difficult to imagine it as a restaurant.

A little farther down Highway 11, in the town of Carlisle, I paid Harvey Sunday a visit. Harvey was the owner of the Country House. Today he lives in a retirement home, in a small room with a bed, a desk, and an easy chair. He shared this room with his wife, Helen, until she died on September 11, 2001—“the day that New York got blowed up,” as Harvey put it. “She died right there,” he told me, pointing to the bed he still slept in every night.

Though nearly ninety and confined to a wheelchair, Harvey’s mind was still razor sharp. He looked me right in the eye as he spoke. His green eyes were so piercing that I had to look away occasionally, pretending to fiddle with my tape recorder. Harvey said he and Helen built the Country House in 1950. He was working on his father’s farm at the time. “We growed hogs and steers and we growed corn and hay and wheat and barley,” Harvey said. “We thought we could work the farm produce into the restaurant.”

Harvey and Helen didn’t know the first thing about the restaurant business, but they worked hard and learned quickly. “We wanted to make it stand out a little,” Harvey said. He added a bell tower to the building, and customers were encouraged to ring the bell. Helen decorated the pine walls with hand-painted trays and ironstone china. She did the landscaping, too, planting the hundreds of flowers that drew the attention of passersby—including a former first lady.

The Country House was a cut above most roadside eateries. In fact, Harvey winced when I called it a diner. It was a restaurant, he gently corrected me. The tablecloths were white. The menu included filet mignon and “choice seafood.”

Harvey was washing dishes in the kitchen the day the Trumans unexpectedly showed up at his restaurant. “I finally got to talk to Harry after they were about ready to go,” Harvey said. “I didn’t want to bother him but I didn’t want to miss him either.” Harvey remembered Harry telling him he was “very happy” with his meal. Harry wasn’t just being nice either. For years afterward, he would recommend the restaurant to friends who were driving through central Pennsylvania. “After that we had a lot more customers from Independence, Missouri, than we had before,” Harvey said.

The restaurant was successful; some days upward of a thousand meals were served. It was hard work, but Harvey and Helen enjoyed it. “What we liked about it was the results,” Harvey said—the financial results. But they had three kids, too, and it was hard to give them the attention they deserved. “We looked around and realized we weren’t spending enough time with the children.” So, in 1960, Harvey and Helen sold the restaurant to the Dutch Pantry chain. The Dutch Pantry closed in 1970, and the U.S. Postal Service bought the building a few years later. It was converted into a post office. The bell tower was removed.

After they sold the Country House, Harvey and Helen took over his father’s farm full time. They finally retired in the late 1980s. The farm has since been turned into a golf course, a development that does not disturb Harvey in the least. “I think it was a good idea,” he told me. “Wish I’d done it myself, but I was too old.”

Harvey slowly wheeled himself over to his desk, moving the chair with his feet. He reached for a framed picture and handed it to me. It was a color brochure from the heyday of the Country House, the kind you might have found on a display rack at a highway rest stop. “Authentic Country Dining!” it announced. “Come to the Country House and discover an atmosphere that is both intriguing and inviting.” I read the copy out loud. “You’ll relax in air-conditioned comfort in one of five handsomely appointed dining rooms.” Harvey smiled.

“If it wouldn’t've been for the kids not getting enough attention,” he said, “we’d've probably still had it.”

In Carlisle, the Trumans picked up the Pennsylvania Turnpike. For Harry, a certified road aficionado, this must have been a thrilling experience.

When it opened in 1940, there was nothing like the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Built on the ruins of an abandoned railroad line, it stretched 160 miles from Carlisle west to Irwin, over and, via seven tunnels, through the Allegheny Mountains. The turnpike was an engineering marvel, with two twelve-foot lanes in each direction, separated by what was then a spacious ten-foot median. (For a time it was fashionable to picnic in the grassy median, until the state police deemed the practice foolhardy.) Access was limited to eleven interchanges, and all intersecting roads passed over or under the turnpike, so there were no intersections—and no traffic lights—and no speed limits. Ten service plazas gave motorists a place to fill their tanks (and themselves) without having to leave the cocoon of the road.

It cost seventy million dollars to build. Franklin Roosevelt, sensing its military value, prodded Congress to kick in $29.5 million. The rest of the money came from the sale of bonds, which would be paid off by collecting tolls of roughly a penny per mile for passenger vehicles. (Today the rate is about six cents per mile.)

Critics derided it as a boondoggle and a “road to nowhere,” but the turnpike proved a stunning success. Traffic the first year was nearly twice as heavy as projected, and toll revenue exceeded $2.6 million, easily enough to meet expenses. (The accident rate was higher than expected, too, so a speed limit of seventy miles per hour was imposed.)

The Pennsylvania Turnpike wasn’t merely a way to get from one place to another; it became a destination in its own right. Tourists came from all over the country to see the self-proclaimed “World’s Greatest Highway,” and the service plazas did a brisk business in turnpike souvenirs: postcards, glasses, mugs, plates, pennants, ashtrays, and countless other trinkets.