Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (2 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

Introduction

My command stands firm like the mountains, and the sun's disk shines and spreads rays over the titulary of my august person, and my falcon rises high above the kingly banner unto all eternity

.

1

Queen or, as she would prefer to be remembered, King Hatchepsut ruled 18th Dynasty Egypt for over twenty years. Her story is that of a remarkable woman. Born the eldest daughter of King Tuthmosis I, married to her half-brother Tuthmosis II, and guardian of her young stepson–nephew Tuthmosis III, Hatchepsut somehow managed to defy tradition and establish herself on the divine throne of the pharaohs. From this time onwards Hatchepsut became the female embodiment of a male role, uniquely depicted both as a conventional woman and as a man, dressed in male clothing, carrying male accessories and even sporting the traditional pharaoh's false beard. Her reign, a carefully balanced period of internal peace, foreign exploration and monumental building, was in all respects – except one obvious one – a conventional New Kingdom regime; Egypt prospered under her rule. However, after Hatchepsut's death, a serious attempt was made to delete her name and image from the history of Egypt. Hatchepsut's monuments were either destroyed or usurped, her portraits were vandalized and her rule was omitted from the official king lists until only the historian Manetho preserved the memory of a female monarch named Amense or Amensis as the fifth sovereign of the 18th Dynasty.

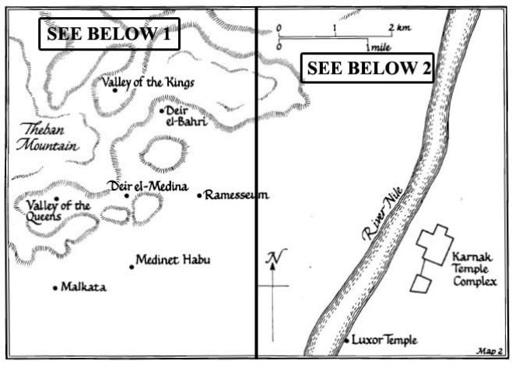

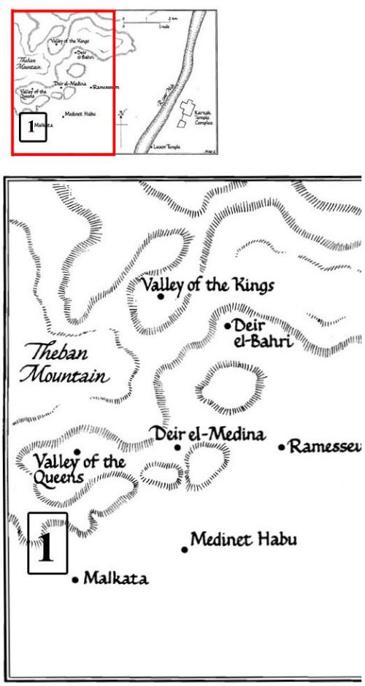

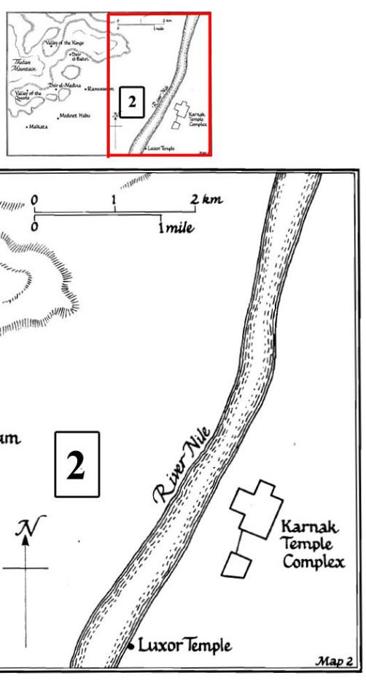

Had Hatchepsut been born a man, her lengthy rule would almost certainly be remembered for its achievements: its stable government, successful trade missions and the impressive architectural advances which include the construction of the Deir el-Bahri temple on the west bank of the Nile at Luxor, a building which is still widely regarded as one of the most beautiful in the world. Instead, Hatchepsut's gender has

become her most important characteristic and almost all references to her reign have concentrated not on her policies but on the personal relationships and power struggles which many historians have felt able to detect within the claustrophobic early 18th Dynasty Theban royal family. Two interlinked questions arise again and again, dominating all accounts of Hatchepsut's life: What made a hitherto conventional queen decide to become a king? And how, in a highly conservative and male-dominated society, was she able to achieve her goal with such apparent ease?

It has generally been allowed that the answer to these riddles must be sought in the character of the woman herself. However, this is where all agreement ends as the identical and rather limited set of facts has suggested radically diverse images of the same woman to different observers, to the extent that a casual reader browsing along a shelf of egyptology books might be forgiven for assuming that Hatchepsut suffered from a seriously split personality. Egyptologists, normally the most dry and cautious of observers, have been only too happy to allow their own feelings to intervene in their telling of Hatchepsut's tale and, more particularly, in their interpretation of the motives underlying her deeds. These feelings have tended to coincide with the beliefs common to a generation, so we find egyptologists at the turn of the century, unaware of the complexities of the Tuthmoside succession and accustomed to the idea of successful female rule personified by Queen Victoria, happy to accept Hatchepsut's own propaganda. To these champions Hatchepsut was a valid monarch, an experienced and well-meaning woman who ruled amicably alongside her young stepson, steering her country through twenty peaceful, prosperous years.

Though unmentioned in the Egyptian king lists, [she] as much deserves to be commemorated among the great monarchs of Egypt as any king or queen who ever sat on its throne during the 18th Dynasty.

2

As a woman who ‘did not fall below the standard of the rest of the 18th Dynasty… [having given] early evidence of her capacity to reign’,

3

Hatchepsut ‘naturally undertook the rule of Egypt, and we are quite justified in saying that the interests of the country suffered in no way through being in her hands’.

4

In summary:

… though she has never been considered as a legitimate sovereign, and though she has left us no account of great conquests, her government must have been at once strong and enlightened, for when her nephew Tuthmosis III succeeded her, the country was sufficiently powerful and rich to allow him to venture not only on the building of great edifices, but on a succession of wars of conquests which gave him, among all the kings of Egypt, a pre-eminent claim to the title of ‘the Great’.

5

By the 1960s, knowledge of early 18th Dynasty history had increased, the climate of opinion had changed, and Hatchepsut had been transformed into the archetypal wicked stepmother familiar from the popular films

Snow White

and

Cinderella

. She was now an unnatural and scheming woman ‘of the most virile character’,

6

and one who would deliberately abuse a position of trust to steal the throne from a defenceless child, thereby cutting short the reign one of Egypt's most successful pharaohs, Tuthmosis III. Hatchepsut was a bad-tempered, ‘shrewd, ambitious and unscrupulous woman [who soon] showed herself in her true colours’.

7

Her foreign policy – the direct result of her weaker sex – was quite simply a disaster and:

her reign is marked by a halt in the policy of conquests started by Ahmose and so splendidly followed by his three successors… [Hatchepsut] was too busy with the internal difficulties which she herself had created by her ambition to interest herself in the affairs of Asia.

8

With the growing realization that Hatchepsut, a flesh-and-blood woman rather than a one-dimensional storybook character, cannot be simply classified as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’, most of these more extreme reactions have been abandoned. However, they have left their mark on the pages of the more popular histories and a significant number of chronicles of 18th Dynasty court life continue to uphold the tradition of the great Tuthmoside family feud. While it is very difficult for any biographer to remain entirely impartial about his or her subject, I am attempting to provide the non-specialist reader with an objective and unbiased account of the life and times of King Hatchepsut, gathered from the researches of those egyptologists who have spent years studying, sometimes in minute detail, the individual threads of evidence which, when woven together, form the tapestry of her reign. It is left for

the reader to decide on the rights or wrongs of her actions. However, it will almost immediately become apparent that Hatchepsut's story unravels to become three interlinked stories: the history of the king and her immediate family, the history of Hatchepsut's memory after her death, and the equally fascinating tale of those who have since studied and interpreted her. It is impossible to study one without making reference to the others, and I have made no attempt to separate the three.

Writing about the public King Hatchepsut has proved to be something of an exercise in detection, as all too often the archaeological record throws up enough clues to intrigue Hercule Poirot while modestly withholding the final piece of evidence needed to prove or disprove a particular theory. Nevertheless, despite the fact that there are huge gaps in our knowledge, the monuments which testify to her achievements and the propaganda texts written to explain her actions do provide us with the evidence needed to reconstruct at least a partial history of Hatchepsut's reign. The private woman – Hatchepsut as daughter, wife and mother – has been far more difficult to reach as we are lacking almost all the intimate details which can help a historical character come alive to the modern reader. Hatchepsut lived in a literate age, but belonged to a society which did not believe in keeping personal written records. The contemporary records which have been preserved are almost invariably official documents which, by their very nature, rarely express private opinions. We have no intimate letters written to, by or about Hatchepsut and no diaries or memoirs to provide us with a glimpse of early 18th Dynasty court life; we cannot even be sure of Hatchepsut's actual appearance, as all her portraits are formal works of art designed to depict the ideal of the divine Egyptian pharaoh. The real Hatchepsut, therefore, remains something of an enigma, although if we look hard enough at her relationships with the daughter whom she clearly loved and the father whom she adored, or if we consider her obvious need to explain her actions and justify her unusual rule whenever possible, we may feel ourselves able to detect a more complex and less secure personality hidden behind the façade of the mighty king.

This lack of more intimate information perhaps explains in part why Cleopatra VII, a transient and far less successful but infinitely better documented queen of Egypt, has attracted the attention of biographers from the time of her death onwards while Hatchepsut has been virtually

ignored by all but the most devoted of specialists. Similarly Queen Nefertiti, short-lived consort to an unconventional king, has, on the basis of one remarkable portrait-head, become immortal, her name synonymous with Egyptian beauty throughout the western world. Hatchepsut herself would almost certainly approve of our inability to pry into her private affairs. All Egyptian kings aspired to conform to the accepted stereotype, and she was no exception. She had no wish to be remembered merely for her sex, which she regarded as an irrelevance; she had demanded – and for a brief time won - the right to be ranked as an equal amongst the pharaohs.