Have His Carcase (48 page)

Authors: Dorothy L. Sayers

correspondent might very wel hit on some word that Alexis had marked in

advance. It might be anything.’

‘Perfectly true. Then the only bit of help we get from this is that the cipher

used was an English word, and that the letters were probably written in English.

That doesn’t absolutely folow, because they might be in French or German or

Italian, al of which have the same alphabet as English; but they can’t be in

Russian at any rate, which has an alphabet totaly different. So that’s one

mercy.’

‘If it’s anything to do with Bolsheviks,’ said Glaisher, thoughtfuly, ‘it’s a bit

surprising they didn’t write in Russian. It would have made it doubly safe if they

had. Russian by itself would be bad enough, but a Russian cipher would be a

snorter.’

‘Quite. As I’ve said before, I can’t quite swalow the Bolshevik theory. And

yet – dash it al! I simply can

not

fit these letters in with the Weldon side of the

business.’

‘What

I

want to know,’ put in the Inspector, ‘is this. How did the murderers,

whoever they were, get Alexis out to the Flat-Iron? Or if it was Bolsheviks that

got him there, how did Weldon & Co. know he was going to be there? It must

be the same party that made the appointment and did the throat-cutting. Which

brings us to the point that either Weldon’s party wrote the letter or the foreign

party did the murder.’

‘True, O king.’

‘And where,’ asked Harriet, ‘does Olga Kohn come in?’

‘Ah!’ said Wimsey, ‘there you are. That’s the deepest mystery of the lot. I’l

swear that girl was teling the truth, and I’l swear that the extremely un-Irish Mr

Sulivan was teling the truth too. Little flower in the crannied wal I pluck you

out of the crannies, but, as the poet goes on to say,

if

I could understand I

should know who the guilty man is. But I don’t understand. Who is the

mysterious bearded gentleman who asked Mr Sulivan for the portrait of a

Russian-looking girl, and how did the portrait get into the corpse’s pocket-

book, signed with the name Feodora? These are deep waters, Watson.’

‘I’m coming back to my original opinion,’ grumbled the inspector. ‘I believe

the felow was dotty and cut his own throat and there’s an end of it. He

probably had a mania for colecting girls’ photographs and sending himself

letters in cipher.’

‘And posting them in Czechoslovakia?’

‘Oh, wel, somebody must have done that for him. As far as I can see, we’ve

no case against Weldon and no case against Bright, and the case against

Perkins is as ful of holes as a colander. As for Bolsheviks – where are they?

Your friend Chief-Inspector Parker has put out inquiries about Bolshevik

agents in this country, and the answer is that none of ’em are known to have

been about here lately, and as regards Thursday, 18th, they al seem to be

accounted for. You may say it’s an unknown Bolshevik agent, but there aren’t

as many of those going about as you might think. These London chaps know

quite a lot more than the ordinary public realises. If there’d been anything funny

about Alexis and his crowd, they’d have been on to it like a shot.’

Wimsey sighed, and rose.

‘I’m going home to bed,’ he declared. ‘We must wait til we get the

photographs of the paper. Life is dust and ashes. I can’t prove my theories and

Bunter has deserted me again. He disappeared from Wilvercombe on the same

day as Wiliam Bright, leaving me a message to say that one of my favourite

socks had been lost in the wash and that he had lodged a complaint with the

management. Miss Vane, Harriet, if I may cal you so, wil you marry me and

look after my socks, and, incidentaly be the only woman-novelist who ever

accepted a proposal of marriage in the presence of a superintendent and

inspector of Police?’

‘Not even for the sake of the headlines.’

‘I thought not. Even publicity isn’t what it was. See here, Superintendent, wil

you take a bet that Alexis didn’t commit suicide and that he wasn’t murdered

by Bolsheviks?’

The Superintendent replied cautiously that he wasn’t a sporting man.

‘Crushed again!’ moaned his lordship. ‘Al the same,’ he added, with a flash

of his old spirit, ‘I’l break that alibi if I die for it.’

XXVI

THE EVIDENCE OF THE BAY MARE

‘Hail, shrine of blood!’

The Bride’s Tragedy

Wednesday, 1 July

The photographs of the paper found on the corpse duly arrived next morning,

together with the original; and Wimsey, comparing them together in the

presence of Glaisher and Umpelty, had to confess that the experts had made a

good job of it. Even the original paper was far more legible than it had been

before. The chemicals that remove bloodstains and the stains of dyed leather,

and the chemicals that restore the lost colour to washed-out ink had done their

work wel, and the colour-screens that so ingeniously aid the lens to record one

colour and cut out the next had produced from the original, thus modified, a

result in which only a few letters here and there were irretrievably lost. But to

read is one thing; to decipher, another. They gazed sadly at the inextricable

jumble of letters.

XNATNX

RBEXMG

PRBFX ALI MKMG BFFY, MGTSQ JMRRY. ZBZE FLOX P.M. MSIU

FKX FLDYPG FKAP RPD KL DONA FMKPC FM NOR ANXP.

SOLFA TGMZ DXL LKKZM VXI BWHNZ MBFFY MG, TSQ A

NVPD NMM VFYQ. CJU ROGA K.C. RAC RRMTN S.B. IF H.P. HNZ

ME? SSPXLZ DFAX LRAEL TLMK XATL RPX BM AEBF HS

MPIKATL TO HOKCCI HNRY. TYM VDSM SUSSX GAMKR, BG AIL

AXH NZMLF HVUL KNN RAGY QWMCK, MNQS TOIL AXFA AN

IHMZS RPT HO KFLTIM. IF MTGNLU H.M. CLM KLZM AHPE ALF

AKMSM, ZULPR FHQ – CMZT SXS RSMKRS GNKS FVMP RACY

OSS QESBH NAE UZCK CON MGBNRY RMAL RSH NZM, BKTQAP

OSS QESBH NAE UZCK CON MGBNRY RMAL RSH NZM, BKTQAP

MSH NZM TO ILG MELMS NAGMJU KC KC.

TQKFX BQZ NMEZLI BM ZLFA AYZ MARS UP QOS KMXBJ SUE

UMIL PRKBG MSK QD.

NAP DZMTB N.B. OBE XMG SREFZ DBS AM IMHY GAKY R.

MULBY M.S. SZLKO GKG LKL GAW XNTED BHMB XZD NRKZH

PSMSKMN A.M. MHIZP DK MIM, XNKSAK C KOK MNRL CFL

INXF HDA GAIQ.

GATLM Z DLFA A QPHND MV AK MV MAG C.P.R. XNATNX PD

GUN MBKL I OLKA GLDAGA KQB FTQO SKMX GPDH NW LX

SULMY ILLE MKH BEALF MRSK UFHA AKTS.

At the end of a strenous hour or two, the folowing facts were established:

1. The letter was written on a thin but tough paper which bore no

resemblance to any paper found among the effects of Paul Alexis. The

probability was thus increased that it was a letter received, and not written by

him.

2. It was written by hand in a purplish ink, which, again, was not like that

used by Alexis. The additional inference was drawn that the writer either

possessed no typewriter or was afraid that his typewriter might be traced.

3. It was not written in wheel-cipher, or in any cipher which involved the

regular substitution of one letter of the alphabet for another.

‘At any rate,’ said Wimsey, cheerfuly, ‘we have plenty of material to work

on. This isn’t one of those brief, snappy “Put goods on sundial” messages which

leave you wondering whether E realy is or is not the most frequently-recurring

letter in the English language. If you ask me, it’s either one of those devilish

codes founded on a book – in which case it must be one of the books in the

dead man’s possession, and we only have to go through them – or it’s a

different kind of code altogether – the kind I was thinking about last night, when

we saw those marked words in the dictionary.’

‘What kind’s that, my lord?’

‘It’s good code,’ said Wimsey, ‘and pretty baffling if you don’t know the

key-word. It was used during the War. I used it myself, as a matter of fact,

during a brief interval of detecting under a German alias. But it isn’t the

exclusive property of the War Office. In fact, I met it not so long ago in a

detective story. It’s just –’

He paused, and the policemen waited expectantly.

‘I was going to say, it’s just the thing an amateur English plotter might readily

get hold of and cotton on to. It’s not obvious, but it’s accessible and very

simple to work. It’s the kind of thing that young Alexis could easily learn to

encode and decode; it doesn’t want a lot of bulky apparatus; and it uses

practicaly the same number of letters as the original message, so that it’s highly

suitable for long epistles of this kind.’

‘How’s it worked?’ asked Glaisher.

‘Very prettily. You choose a key-word of six letters or more, none of which

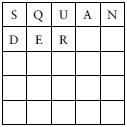

recurs. Such as, for example, SQUANDER, which was on Alexis’ list. Then

you make a diagram of five squares each way and write the key-word in the

squares like this:

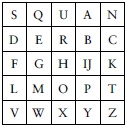

‘Then you fil up the remaining spaces with the rest of the alphabet in order,

leaving out the ones you’ve already got.’

‘You can’t put twenty-six letters into twenty-five spaces,’ objected Glaisher.

‘No; so you pretend you’re an ancient Roman or a medieval monk and treat

I and J as one letter. So you get this.’

‘Now, let’s take a message – What shal me say? “Al is known, fly at once”

– that classic hardy perennial. We write it down al of a piece and break it into

groups of two letters, reading from left to right. It won’t do to have two of the

same letters coming together, so where that happens we shove in Q or Z or

something which won’t confuse the reader. So now our message runs AL QL

IS KN OW NF LY AT ON CE.’

‘Suppose there was an odd letter at the end?’

‘Wel, then we’d add on another Q or Z or something to square it up. Now,

we take our first group, AL. We see that they come at the corners of a

rectangle in which the other corners are SP. So we put down SP for the first

two letters of the coded message. In the same way QL becomes SM and IS

becomes FA.’

‘Ah!’ cried Glaisher, ‘but here’s KN. They both come on the same vertical

line. What happens then?’

‘You take the letter next below each – TC. Next comes OW, which you can

do for yourself by taking the corners of the square.’

‘MX?’

‘MX it is. Go on.’

‘SK,’ said Glaisher, happily taking diagonals from corner to corner, ‘PV,

NP, UT –’

‘No, TU. If your first diagonal went from bottom to top, you must take it the

same way again. ON = TU, NO would be UT.’

‘Of course, of course. TU. Hulo!’

‘What’s the matter?’

‘CE come on the same horizontal line.’

‘In that case you take the next letter to the

right

of each.’

‘But there isn’t a letter to the right of C.’

‘Then start again at the begininning of the line.’

This confused the Superintendent for a moment, but he finaly produced DR.

‘That’s right. So your coded message stands now: SP SM FA TC MX SK

PV NP TU DR. To make it look prettier and not give the method away, you

can break it up into any lengths you like. For instance. SPSM FAT CMXS

KPV NPTUDR. Or you can embelish it with punctuation at hapazard. S.P.